The Aram Live: an evening of ease, comfort and joy hosted by Tahmina Begum

By Alma Fabiani

Published Jul 22, 2021 at 11:57 AM

Reading time: 2 minutes

In partnership with Selina

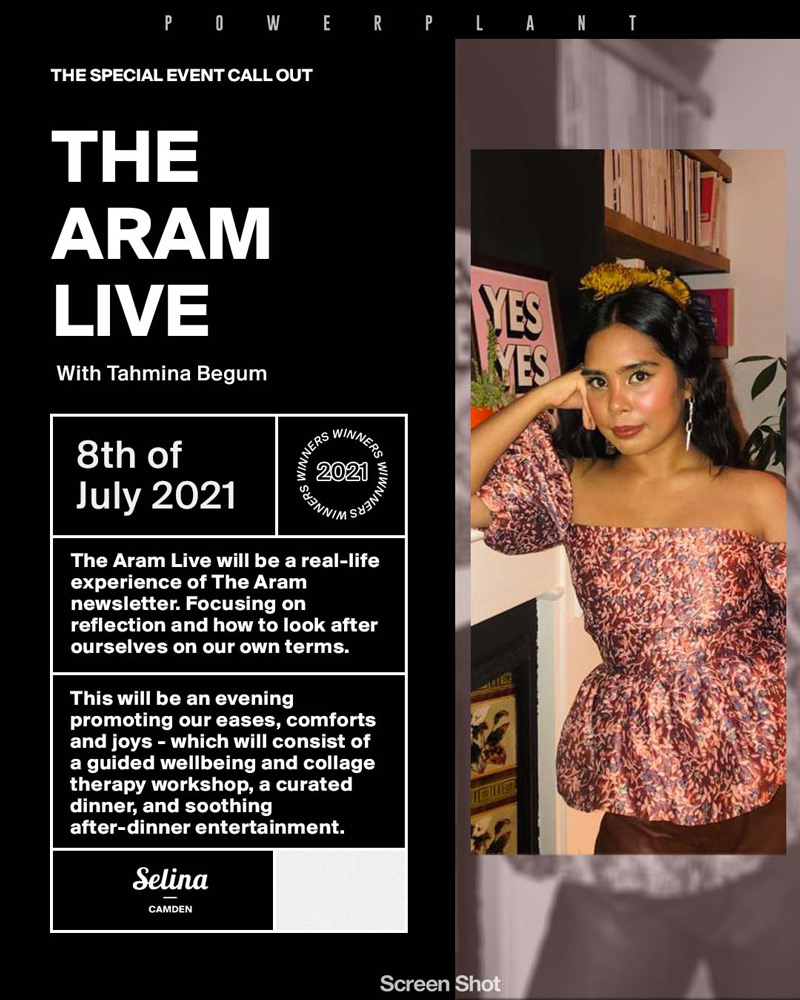

We’ve all had a tough time in the last year or so—some undoubtedly more than others—but many of us are still feeling the weight of it on our shoulders and mind. As restrictions begin to slowly ease, it’s important for you to not rush so quickly into ‘normal life’ and find the time to celebrate the ‘small wins’ you’ve achieved during the pandemic. And what better way to do so than through an evening spent with the wonderful Tahmina Begum, writer, creative consultant and founder of The Aram newsletter?

As one of the ten winners of The Special Event Call Out we launched in partnership with Selina last month, Begum brings you The Aram Live, which will be taking place at Selina’s new Camden location on Wednesday 4 August. Because we couldn’t wait more than ten days to learn a bit more about what Begum had in store for you, we sat down with her to discuss all things The Aram.

First things first, if you’re not familiar with The Aram, let us clarify things for you. “The Aram is a bi-monthly newsletter that centres on women of colour and Muslim women and focuses on our ease and joy,” Begum explained, adding that “‘Aram’ in Bangla means ‘ease’ and ‘comfort’. As important as it is as a woman of colour to speak about the traumas and lived experiences we have gone through, we don’t hear enough about what in turn brings us a lot of ease and the journey in preserving our peace. I write a personal essay every other week and also for the ‘Getting Aram With’ section, I profile a WOC/Muslim woman and ask her three questions on what’s currently bringing her joy and aram.”

Now at its 21st edition, The Aram has already charmed Begum’s ultra engaged audience and more. In that sense, marking its success by connecting face to face with the people the writer shares so much with was the next logical step forward. So, what should you expect from the upcoming event?

Focusing on reflection and how to look after ourselves on our own terms, The Aram Live will consist of a guided wellbeing and collage therapy workshop, a curated dinner, and soothing after-dinner entertainment. “I will be hosting a guided creative reflective workshop. This will include freewriting exercises, collaging and looking back on what lessons we’re taking with us that we learnt during the pandemic,” Begum told us.

“We’re all rushing to get back to ‘normal life’ so this workshop is about really taking a second and appreciating everything we’ve endured but also celebrating our growth in what will hopefully not be a wishy-washy exercise. Moments of gratitude and all that good stuff. There’s also the added option of a Bangladeshi-inspired 3-course vegan dinner,” she further explained about the rest of the evening. The optional dinner—although who would want to miss out on that?—will be held at Selina’s on-site plant-based restaurant, POWERPLANT.

For the event’s after-dinner experience, which will be open to everyone, Begum didn’t confirm nor deny anything just yet, although a little bird told me spoken word poetry might be on the cards… That stays between us though. Whether you’re interested in experiencing The Aram newsletter in person or just looking for “an evening of ease,” Begum is more than happy to welcome you into her own cosmos, adding that “those who wish to embrace all of who they are post-lockdown” are part of the audience she’d like to reach too.

So, what are you waiting for? Grab yourself a ticket before they’re all gone! You can cop your ticket for the guided wellbeing and collage therapy workshop here for £27.50, pre-pay £37.50 for the Bangladeshi-inspired 3-course vegan dinner here, and even RSVP for free for the mystery after-dinner experience here. I’ll see you there on Wednesday 4 August!

And if you’re not sure just yet whether The Aram Live is for you, here’s what Begum herself had to share, “Life’s too short to not know where you’re going and it’s also too short to not preserve your peace so that’s exactly what the evening will be about among like-minded people. I’m excited to see readers get together and inshallah, become friends too. Plus, I’m curating the mocktails and they sound HEAVENLY.” Who could say no to this, right?