Fika is the tech app helping students who struggle with their mental health

In 2018, the Times described today’s students as the “Snowflake Generation,” referring to millennial’s apparent hyper-sensitivity to both personal and social-political issues. Millennials are often portrayed as ‘moaners’ complaining about the harshness of being young in today’s turbulent world. But the truth is that recent reports speak loudly about the mental health crisis students are going through. In the UK alone, two in five students struggle with anxiety, many drop out from their courses (26,000 students in England who were studying for their first degree in 2015 did not finish their courses), and the alarming rate of suicide among students seems to be increasing. According to a report from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) conducted in England and Wales, there is one death every four days. In Oregon, US, a new bill allows students to take ‘mental health’ days off from school. In the UK, while the NHS and university-based counsellors have been struggling to keep up with the demands coming from students in need of mental health support, tech-based projects such as Fika are working on preventing—rather than solving—this tragic epidemic, with the help of what is called ‘emotional fitness’.

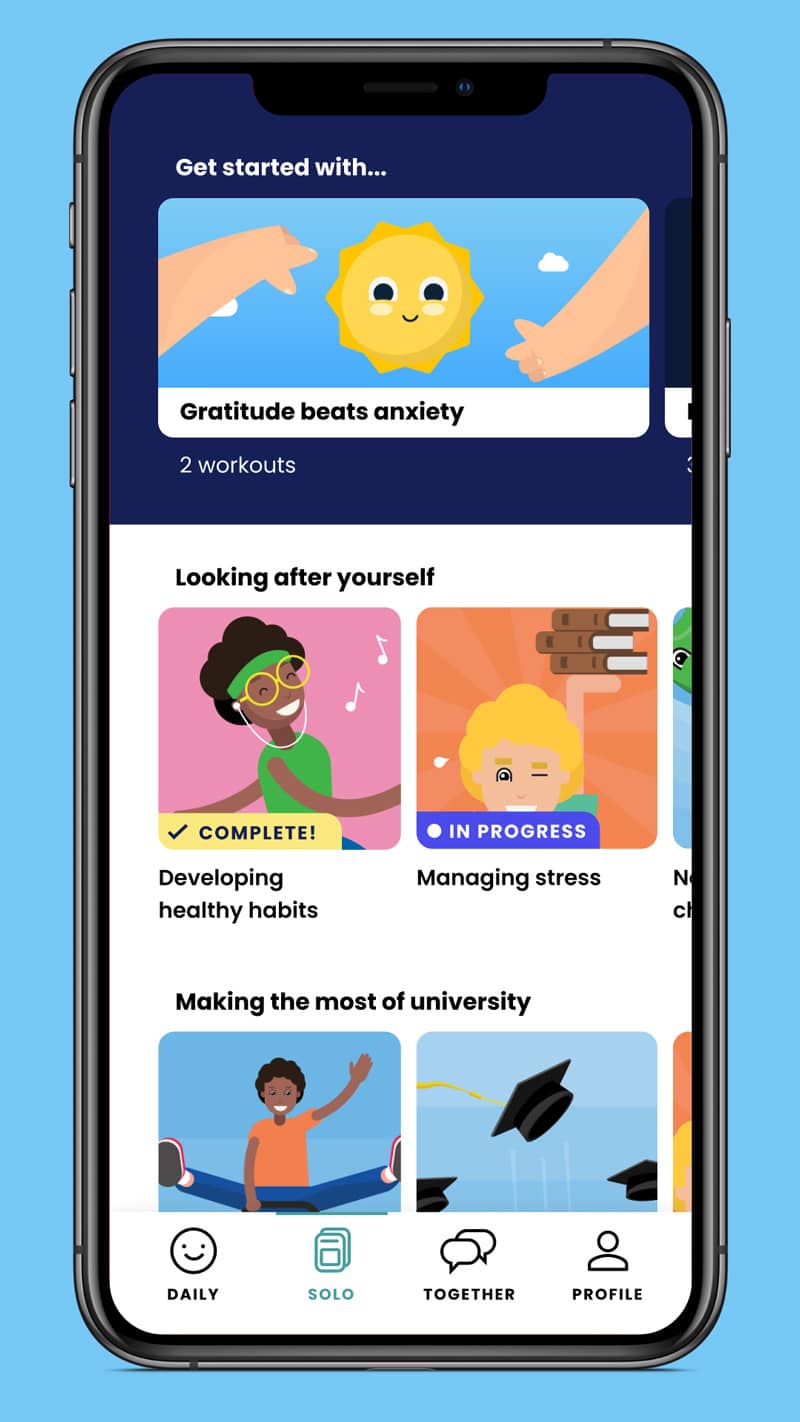

After his best friend committed suicide, Nick Bennett realised how crucial emotional education is, and co-founded Fika, an education technology company and app that offers university students the tools and the coping mechanisms they need to prevent mental health-related symptoms. Fika provides five-minute emotional workouts designed to build students’ resilience, confidence, and empathy, as well as encouraging social inclusion at universities. “We really believe in the potential of combining science with technology to create a scalable, self-sustainable solution for student wellbeing. What makes Fika exciting is that it’s about prevention, rather than cure. Both are important parts of the answer, but rather than parking the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, we think students should be proactively building emotional muscle every day, from the day they arrive at university,” Nick Bennett told Screen Shot.

But while it seems crucial to provide students with emotional structures, how can universities and similar institutions improve the system that is partially responsible for the mental health crisis among young people? So far, Fika has partnered with several universities across the country, including the University of Exeter and London Business School, and in November it will be hosting its first Fika think tank, ‘Building a Brighter Future for Student Wellbeing’, to explore how universities’ system could change from the inside.

Redesigning the curriculum to include emotional education is one of the options Fika is exploring, particularly after its recent survey has demonstrated that both students and educational workers believe it would have an enormous impact on students’ wellbeing. Meanwhile, universities across the country are slowly doing their part to address the issue. Last year, the University of Bristol became the first university in the UK to offer optional ‘Science of Happiness’ courses as part of the curriculum. Similarly, the Oxford Mindfulness Centre offers mindfulness courses for students and staff members at the University of Oxford, while other psycho-educational initiatives are being introduced across the sector.

Anxiety, depression, loneliness, bullying, body image issues and ‘fear of missing out’ are just some of the many phenomena that emerge from using social media and the internet on a daily basis. Where does Fika, as an app, stand in regards to social media’s responsibility for the youth’s mental health crisis? Reports show that both the internet and social media have been causes as well as cures to the mental health crisis, more specifically affecting the so-called ‘digital natives’. Speaking about this matter, Bennett told Screen Shot “We’re very committed to exploring and understanding how people’s relationships with technology affect their mental health, and, ultimately, just like our relationships with offline media (newspapers, magazines), we think there’s a mixture of good and bad at play.”

Fika cannot be the only answer to our generation’s mental health crisis. As Bennett explained, student services such as counselling and clinical support are still very much required to support students in distress. But there is no doubt that additional tools to tackle this crisis are needed urgently. In a time when institutions are struggling to respond to this emergency, means to preserve the wellbeing of students, and young people in general, can only be welcomed with open arms.