How the bikini bridge replaced the thigh gap as the latest toxic body image trend

Remember the term ‘thigh gap’, which refers to the space some people have between their inner thighs when standing upright with their feet touching? Around 2013, the whole world (and Tumblr) went crazy for it—leading many individuals to consider it a special feature of physical attractiveness and physical fitness in women.

Among teenage girls mostly, the thigh gap had become a beauty ideal, which in turn led them to resort to extreme dieting or even surgery in order to try to obtain it. Little did we know that the thigh gap is a physiognomic feature natural only for women with a certain type of body shape and bone structure—one that most women do not have. Attempts to attain the unattainable ideal resulted in a myriad of problems like low self-esteem and even eating disorders.

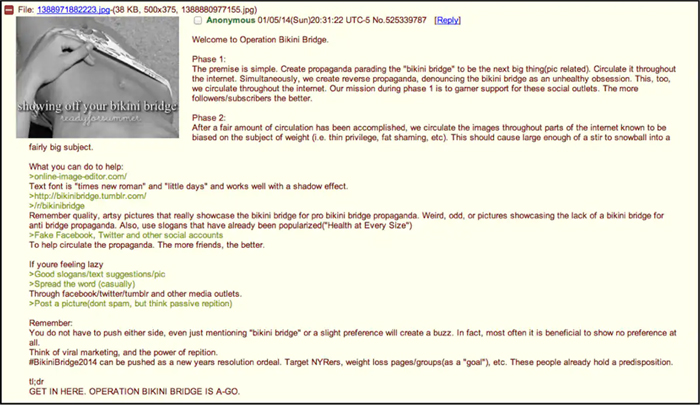

But things didn’t stop there. In 2014, another harmful body image trend appeared online: the bikini bridge. Defined as “when bikini bottoms are suspended between the two hip bones, causing a space between the bikini and the lower abdomen,” the trend originated in the US in January, when a user on the /b/ section on the imageboard 4chan made up a parody of popular ‘thinspiration’ memes through the launch of ‘Operation Bikini Bridge’.

According to a posting on the website, users intended to spread content across social media regarding bikini bridges as a joke. It was quickly reported on by US television programme Today on 7 January. Several commentators critiqued the posts for displaying insensitivity or being “dangerous” for women with an eating disorder. But that didn’t help much, teenagers had already switched their thigh gap obsession for the bikini bridge.

A thinspo hoax

Urban Dictionary defines thinspiration, also shortened to thinspo, as a term “used by people suffering from eating disorders to help keep them inspired. The idea behind thinspo is that it helps motivate and inspire you to lose weight and become or stay thin.” Thinspo usually consists of photos of unhealthily skinny people—sometimes even taking the forms of celebrities who have lost a great deal of weight. But thinspo can also be anything besides just photos. Book quotes, song lyrics, films…you name it.

Although thigh gaps were first celebrated as physical attributes denoting attractiveness in women because of our society’s harmful beauty standards and obsession with thinness, the bikini bridge was initially introduced as thinspiration propaganda. It goes without saying that both have had an incredibly toxic impact on those who were exposed to such unrealistic standards.

It exploded online, and Tumblr pages as well as Instagram accounts dedicated to either showcasing the bikini bridge or denouncing it flooded social media platforms. The bikini bridge became mainstream and 4chan’s little experiment proved to be a horrifying success.

How harmful body ideals spread through social media like wildfire

Trends such as thinspiration and fitspiration provide insight into the darker side of how social media shape attitudes to women’s bodies. However, what was less understood at the time is how body ideals are communicated through social media and what makes them gain traction.

The Conversation went on a mission to analyse the viral spread of the bikini bridge and identified four factors that contributed to its notoriety. Firstly, it was introduced as a ‘simple’, singular body goal: the term ‘bikini bridge’ offered catchy mass appeal as something that users could strive to achieve.

Secondly, it didn’t really matter if the notion of a bikini bridge was real or fake—it was believable as it drew on innate cultural beliefs about how a woman’s body should look. Thirdly, the bikini bridge was accelerated by other online communities, such as pro-anorexia groups and online pornographers, who leveraged its hashtag to spread their own harmful messages.

And finally, online users helped further spread the bikini bridge trend by voicing conflicting opinions about it—creating a very public conversation. The phenomenon caught on quickly because it reflected the cultural expectations placed on women’s bodies and what was seen as culturally valuable.

Of course, the idea of beauty is constantly evolving as whom we deem ‘beautiful’ is a reflection of our values. Today, it’s more inclusive than ever, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t more work left to be done. Just as it’s helped so many of these toxic trends grow, social media has also proved to be a great help in amplifying the voices of minority communities, so that their calls for representation can’t be so easily ignored.

The new definition of beauty is being written by a selfie generation: people who are the cover stars of their own narrative. Beauty is shifting into political correctness, cultural enlightenment, and social justice instead of thigh gaps and bikini bridges.