Opinion

Petitions and marches don’t change politics but mass action can

By Tasmin Lockwood

Opinion

Petitions and marches don’t change politics but mass action can

By Tasmin Lockwood

Published Oct 15, 2019 at 11:16 AM

Reading time: 4 minutes

Global politics

Oct 15, 2019

A protest is often categorised by placards, people and marching. But, in essence, it is the expression of disapproval. While today’s digitally-defined world is full of such, be it via social media or the sharing of satirical memes, the rise of online petitions and ease of organising mass action means protesting is more accessible than ever. This has seen rise to fickle engagement, with petitions emerging as the go-to resource for expressing dissatisfaction about almost anything.

Currently, there are 2,116 open petitions on the UK’s official petition site, 25 of which with just six signatures, the lowest current count. The most signed petition, ‘Do not prorogue Parliament’, has 1,724,467 signatures. The government must respond to petitions on the site with over 10,000 signatures, while those over 100,000 will be considered for debate in parliament. This seems like a more effective way of influencing policy change, although it is also an official record of civil dissidence. Petitions are undoubtedly great tools for gauging the public feeling, due to vast participation, and are more inclusive than marches, which have a complex culture.

Screen Shot spoke to animal rights activist Leigh Venus, who suggested petitions are “a more acceptable form of activism for the more buttoned-down and pearl-clutchy in the crowd.” Though generally ineffective in directly influencing policy, petitions are now an embedded feature in the process, where opting not to sign may be used to counter the motion, as a claim of non-support.

Clare Josa, who co-led the EU VAT Action Campaign that changed EU law, told Screen Shot, “Petitions are effective at highlighting an issue, but what counts for policy change is letters and surgery visits to MPs. The danger is that most people sign a petition and think that’s their job done. It isn’t. You also need to write to or visit your MP. The number of letters an MP receives on a topic is tallied up and used to judge how important it is.”

Petitions do, however, offer a gateway to change; a foundation for greater action. “While the problem of clicktivism and people feeling like they are making a difference by mashing a like button is a biggie, the rise of social media has no doubt amplified the reach of campaigns and protests and, wielded with caution, is an incredible force for good,” Venus said. “Clicktivism got me going onto the streets for a start.”

Venus admitted he does not seek petitions out but he signs them when they “come through email from organisations I follow,” a sign that shows petitions and marches are intertwined and support a bigger issue. His wife, Laura, who is also an activist, signs petitions as well, but doesn’t expect mind-blowing changes: “If their aims are to end up in front of the government I don’t hold out much hope—the government is a complete mess,” she said.

Jonathan Cable, author of Protest Campaigns, Media and Political Opportunities agreed with Laura Venus: “The revoke Article 50 had over 6 million signatories, but what those in power do with that information is something else entirely.”

Meanwhile, attendance of climate rallies has increased, Extinction Rebellion is truly revolting. There have been nine major Brexit marches, with many more at a regional level. And yet, the outcome of Brexit has not changed, nor did climate change policy. Marches rarely bring about direct change. This is why Alex Lockwood, lecturer at Sunderland University, was put off marching for 15 years after his first time. “It was the march against the Iraq War. When it didn’t change anything, I thought, what’s the point?” he said.

Mr Cable argues marches aren’t completely ineffective, but they demonstrate the strength of feeling about an issue. “Marches in the run up to the Iraq War didn’t stop that war, but probably prevented a future one against Iran, or Syria,” he explained.

Any form of protest must be used strategically, and history shows direct action plays an important role in this strategy. The Suffragettes marched but also endured hunger strikes. Civil disobedience won women the right to vote. The power of the people was also a significant factor in the fall of communist governments and the Berlin Wall. Today, a familiar situation has emerged in Hong Kong.

However, while direct action is effective in getting headlines, it isolates marchers seeking peaceful protest and casts a negative light onto the cause and activism more generally, resulting in many activist groups branding themselves as non-violent.

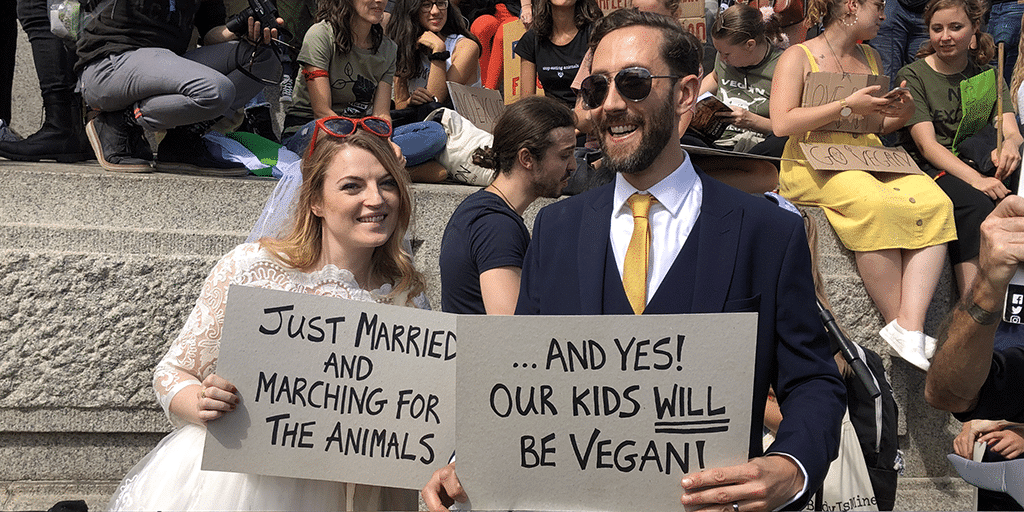

Instead, protesters can achieve media coverage surpassing the ‘regular’ headlines through inclusivity. For example, newlyweds Leigh and Laura Venus marched in their wedding outfits, causing the pair to go viral. “Humour gets clicks,” Laura Venus shared. “We wanted to have fun and show that being a vegan activist isn’t just black T-shirts and seriousness. Our friend became a cow with a sign saying ‘leave my tits alone’, which was a featured photo in a news article.”

Perhaps petitions and marches are not for the government, but for the people—for fellow activists who crave solidarity, to know they are not alone. Public protest has long played an integral role in increasing and maximising coverage of a cause and support the public’s understanding of politics. “Marches set off ripples of change. The visibility of marches leads people who may have been on the sidelines to get involved, as they see their friends and neighbours marching,” said Elizabeth Sawin, co-director of Climate Interactive. This is evident in climate activism swaying public opinion in the US.

Mr Lockwood, who began marching again in August 2019 as a volunteer for Animal Rebellion, witnessed the change that marches have undergone in the last few years: “My sense of what a march is for has changed. I now see that marches are about shows of solidarity and community.”

While petitions and marches may not be effective tools for policy change in isolation, their collective action inspires further action. Mass participation cannot be ignored. And that’s the true goal of protest, to push a cause into the public debate and into the minds of politicians.

When do marches and petitions become more than just a collective action and actually work and change things? One of the first major milestones for climate action was in 2007, when communities across America came together under the Step It Up banner. A decade later, it is only now just being recognised as an emergency—while a climate change denier sits as the leader of ‘the free world’.

But hope is not lost, and maybe the time has finally come. Sawin summarised: “It’s like a snowball rolling downhill. It starts small, but once it gets going the pace of change picks up dramatically.” So get ready for a change of pace, because Extinction Rebellion definitely is.