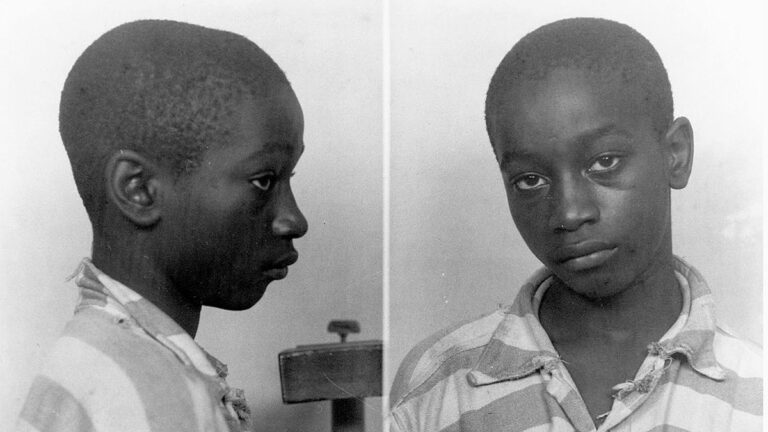

14-year-old black boy executed by electric chair proven innocent 70 years later

George Stinney Jr. became the youngest person to have ever been executed by electric chair in the US, at only 14 years old. 70 years then passed and, in 2014, he was finally proven innocent. So, what is the true story behind the ten minutes that led a harmless young African-American boy to an unjust, racist and tragic execution?

Stinney Jr. was wrongfully killed in the Deep South of the US in 1944, right in the midst of the Jim Crow era. Jim Crow laws, named after a Black minstrel show character, were a collection of state and local regulations that legalised racial segregation. They lasted from post-Civil War to 1968, spanning around 100 years and were put in place after the abolition of slavery to continue the marginalisation of black Americans in the country. Just some of the ways this was enacted was by denying them the right to vote, hold jobs, get an education or basically any basic civil rights that every single person should have the freedom to. Anyone who attempted to defy Jim Crow laws would be arrested, faced with fines, jail sentences, violence and even death.

White and black people were physically separated by railroad tracks where Stinney Jr’s. family lived in the mill town of Alcolu, South Carolina; a location they were forced to leave when he was falsely accused of killing two local white girls—11-year-old Betty June Binnicker and 7-year-old Mary Emma Thames. It took a jury, made up of solely white men, just ten minutes to find the boy ‘guilty’.

As the case was told, the girls were riding their bicycles in Alcolu looking for flowers when they saw both Stinney Jr. and his younger sister Aime, who had taken their family’s cow out grazing, and asked them whether the two might know where to find maypops—the edible fruit of passionflowers (commonly referred to as passionfruit). The girls walked on after realising the brother and sister didn’t know where to find what they were looking for, which is when a lumber truck allegedly drove past, witnessing the interaction.

The two girls Binnicker and Thames didn’t come home that day, the local community responded with a town-wide search by hundreds of Alcolu residents, including Stinney Jr’s father. The bodies were found in a ditch the following day, with no apparent sign of struggle, but still what were said to be violent deaths that involved multiple head injuries.

The Post and Courier described the scene where they were found, “The girls’ bodies were stiff when the preacher’s boy found them in a shallow, waterlogged ditch in the woods. They were on their backs, like a pair of discarded dolls, bruised and broken beyond repair. On top of them lay a bicycle, its front wheel gone from the frame.”

The publication went on to explain that following an examination, it was clear the method of murder was bloody. Thames had a prominent cut and hole that permeated straight through her forehead into the skull while Binnicker displayed signs of multiple blows to the head—the doctor noting it was “nothing but a mass of crushed bones.”

This is where the story splits in two, the first false and historically final version led to the abrupt end of Stinney Jr’s life. According to seemingly no one in particular, the young boy supposedly followed and single-handedly beat the two girls to death with a railroad spike.

The second version that solidified only as much as a whisper, is that Stinney Jr. and his sister simply continued with their own business—the girls to theirs, which led them to the home of a white lumber mill family where they asked if the wife of the house would join them on their hunt for maypops. She said no, but the son of the house drove up in his logging truck and offered to take the girls off to find their maypops while he unloaded the logs. They jumped in. And then? Well, no other versions really mattered, because suspicion fell on Stinney Jr. as he was pointed out to be the ‘mean’ kid in town.

The county law enforcement officers were tipped that Binnicker and Thames were seen talking to Stinney Jr., so they stormed over to his home where the boy was handcuffed and interrogated without his parents, an attorney or any witnesses whatsoever. The police claimed that the 14-year-old confessed to murdering the two girls. According to All That’s Interesting, an officer named H.S. Newman wrote in a statement that he “arrested a boy by the name of George Stinney. He then made a confession and told me where to find a piece of iron about 15 inches long. He said he put it in a ditch about six feet from the bicycle.”

All the while Stinney Jr. was being detained alone, without any telling as to where—not even his parents knew where he was being kept. At that time in history, 14 years of age was considered to be an age of responsibility, as teens experienced puberty. He was never seen alive again by his siblings after that day, alone throughout the 83-day detainment and alone when faced by a solely white jury. Only until he was in his casket was the family together again.

In 2014, The Guardian conducted an interview with the boy’s family, writing that Aime will never forget the last time she saw her brother alive, “She was eight at the time, hunkering in the chicken coop, scared half to death, when two black cars drove up to their house. Neither her mother, also [called] Aime, a cook, nor her father, George senior, were home when white law enforcement officers came and took away George and her stepbrother, Johnny, in handcuffs. Johnny was later let go. She idolised George and followed him everywhere. He called her his shadow.”

The events of that day in 1944, when Aime and Stinney Jr. came across the girls were said to be clear in her mind, because “no white people came around” to the black side of town. She continued, “We didn’t see those girls no more. But somebody followed those girls and killed them.” Realistically, no black child would threaten a white kid without there being strong repercussions at that time, as Aime stated, “We didn’t fool around with white people.” However, as I said before, Stinney Jr. was pointed out by someone down the ‘grapevine’, turning him into an easy suspect.

According to The Guardian, back in 1995, “WL Hamilton, George’s seventh-grade teacher, who is black, told the Item newspaper that he had a temper and had gotten into a fight with a girl at school, scratching her with a knife.” Aime said she phoned Hamilton after she read the story. “That bastard. That was a damn lie. When I heard about that lie Mr Hamilton told I called him up. I said my name is Aime Stinney and you said my brother was a bad boy. You’ve got one foot on a banana peel and the other going straight to hell.”

Stinney Jr’s execution was not without protest, both white and black ministerial unions petitioned for his release based on his young age. Hundreds of letters came through the governor’s door begging for mercy, but none of it was enough to save him from the execution that occurred on 16 June 1944. A bible under the 14-year-old’s arm, he was strapped into the adult-sized electric chair.

70 years later

Stinney Jr’s siblings never gave up on claiming their brother’s innocence, and in 2014, 70 years too late, the jury resided in the fact that he was falsely accused and sentenced to his death. His siblings convinced the court that Stinney Jr. of course had an alibi, he was with his sister Aime [now married as Aime Stinney Ruffner, 77 years old when the case closed] and their cow. Their brother’s cellmate at the time of conviction, Wilford ‘Johnny’ hunter, reported that the boy had denied murdering the girls as well.

By 17 December 2014, Judge Carmen T. Mullen relieved Stinney’s murder conviction, calling the death sentence “a great and fundamental injustice.” The 14-year-old innocent boy’s siblings felt that “a cloud just moved away,” when hearing the news. George Stinney Jr. can never have his life back, but his story will be told, and told again, as well as every other racial unjust prosecution. Echos of the past lie all around us still to this day—we infinitely, generation after generation, are on stand to call out discrimination and inequality.