Calvin Klein’s latest #ProudInMyCalvins campaign is a celebration of LGBTQIA+ journeys

LGBTQIA+ representation is fundamental, especially during Pride Month, as it can have a powerful impact in terms of influencing ideas and attitudes towards the community. While putting queer and trans people at the forefront is one way of championing the many voices of the community, it is also crucial for those same voices to be celebrated—not only for who they are today, but for the journey they embarked upon to express their identity.

That’s the exact message Calvin Klein is amplifying this Pride 2021 through a continuation of its renowned #ProudInMyCalvins campaign, which lets you learn from some of the biggest influences of today’s LGBTQIA+ community as they look back on the transformative events that shaped their lives.

Over the years, Calvin Klein has put great effort into championing the LGBTQIA+ community and advocating for its rights. Unlike other brands who have been called out for only doing so once June’s Pride Month comes along, Calvin Klein is known to partner with multiple non-profit organisations in support of LGBTQIA+ advocacy, equality, and safety—not for one month, but throughout the year.

This year, the brand has rounded up an impressive cast of LGBTQIA+ talents—both on-camera and behind the scenes—to bring their stories to the world, celebrating the defining moments of each of their personal journeys. Calvin Klein worked with acclaimed LGBTQIA+ photographers Gorka Postigo Breedveld, Matt Lamb, Ryan McGinley, Campbell Addy, Collier Schorr and Vivi Bacco who in turn captured eight queer and trans cultural leaders in a video series reflecting on the pivotal moments in their lives.

While each of the cast stands out for their highly individual background and rare talent, they are all united in their shared passion for—and impact on—the LGBTQIA+ community. These include Venezuelan musician Arca, electronic musician Honey Dijon, spoken word poet and activist Kai Isaiah-Jamal, singer-songwriter King Princess, actor and singer Isaac Cole Powell, make-up artist Raisa Flowers, visual artist Samuel de Saboia and Elite star Omar Ayuso.

Arca (she/her) shot by Gorka Postigo in Barcelona

Venezuelan, Barcelona-based musician, singer, composer, record producer, and DJ Arca has released four studio albums and has contributed production work to artists such as Björk, Kanye West, FKA twigs, Kelela, and Frank Ocean. Arca came out as non-binary in 2018, later adding that she identifies as a trans woman, and goes by the pronouns she/her.

In 2020, in an interview for i-D, she stated, “I see my gender identity as non-binary, and I identify as a trans Latina woman, and yet, I don’t want to encourage anyone to think that my gayness has been banished. And when I talk about gayness, it’s funny because I’m not thinking about who I’m attracted to. It’s a form of cultural production that is individual and collective, which I don’t ever want to renounce.”

In Calvin Klein’s new #ProudInMyCalvins campaign, Arca shares the story of the first time she gave herself permission to cruise—meaning: to visit a place in search of a sexual partner.

“Something about the magnetism in the air that day made it possible for me to have the courage to come up to him. In that moment of connection, I felt a vitality. I felt free of doubt and elated.”

Honey Dijon (she/her) shot by Matt Lambert in Berlin

Honey Dijon has been a vocal advocate for trans rights and awareness, speaking from her experience as a black trans woman DJ in dance music. Referring to a moment in “1990-something,” she speaks about a time where she went out with a friend in New York and met another trans woman: “She saw me and said to me, ‘you belong in a skirt’ and it was the first time in my life that someone had seen me before I saw myself. I felt light, happy, I felt warm, loved, seen and accepted.”

Kai Isaiah-Jamal (they/them) shot by Campbell Addy in London

In their video for Calvin Klein, titled The Moment: transition 2.0, poet, activist and model Kai Isaiah-Jamal shares about their experience as a trans person of colour.

“I’ll never forget it. I call it my transition 2.0. Being able to step back into femininity and celebrate that glory…where once those things would have been really triggering. I felt weightless and free.”

King Princess (pronoun-fluid) shot by Collier Schorr in New York City

The singer, songwriter and producer from Brooklyn, New York, quickly rose to fame after her debut single ‘1950’, released in 2018. It was through her mother, who worked in fashion, that she first found her LGBTQIA+ family. For King Princess—real name Mikaela Straus—the moment she shed light on was when she first felt lucky to be gay, “I started to realise that I was part of this tapestry of queer people that have made really powerful, moving work. When I realised that, everything made sense.”

Isaac Cole Powell (he/him) shot by Ryan McGinley in New York City

Similar to Arca, Isaac Cole Powell had his moment through a personal encounter. Powell’s happened in 2010, when he found himself alone with someone he was very attracted to. “I kept waiting for him to do it,” he says. “My hand just crept down my thigh, waiting for it to brush up against him. And then it finally did, and it was like electricity. My whole body was flashing colours.”

“I just knew there was no going back from that feeling, I was forever changed in that moment because I finally knew what it felt like to touch another boy.”

Raisa Flowers (she/her) shot by Ryan McGinley in New York City

Beyond her impeccable make-up looks, Raisa Flowers is also a fierce advocate for representation of all types in the fashion industry. “She’s been vocal about the pushback she’s received as a plus-size, black and queer makeup artist and works hard to ensure inclusivity for all types of bodies and faces,” writes Elle.

In her #ProudInMyCalvins video, titled The Moment: I Didn’t Care, Flowers explains how she learned to channel her inner-power through teenage rebellion after shaving her head while attending Catholic school. “My principal was like, ‘We need to watch her because she’s going to be wild’,” she recalls. “I felt like a badass.”

Samuel de Saboia (he/him) shot by Vivi Bacco in São Paulo

Calvin Klein also travelled to Brazil to link up with bisexual Afro-Indigenous Brazilian artist Samuel de Saboia. Sharing his own defining moment, de Saboia recalls, “I never kissed a guy till that moment. Heart pumping. Like, I could literally see my chest just moving.”

“My parents are preachers. So, once I got back home at the end of the day, my parents already had a photo of me kissing this guy. I just felt so hurt by the idea that someone would look at another person and feel entitled to change and mess up their whole life. Within one week, I packed my bags and went to São Paulo. And everything started,” adds de Saboia.

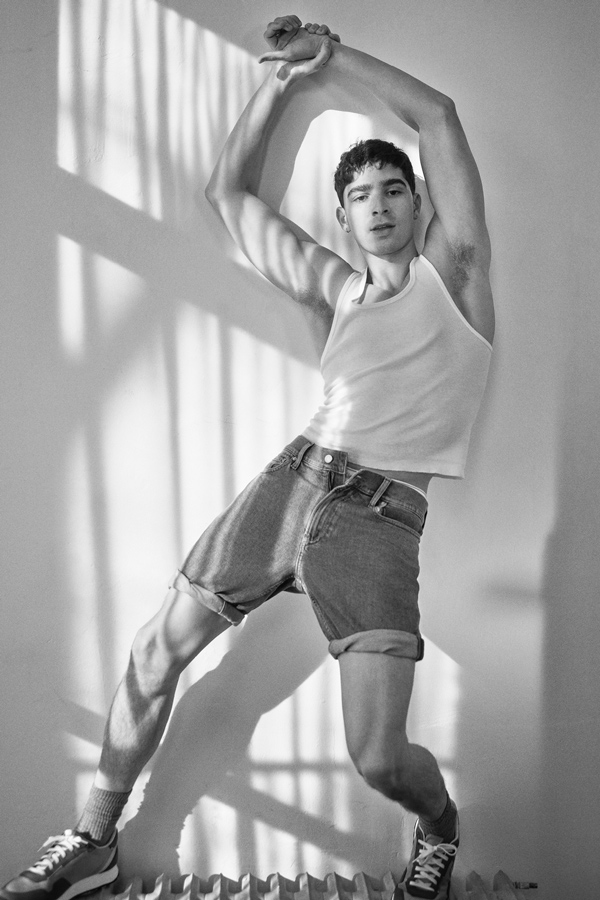

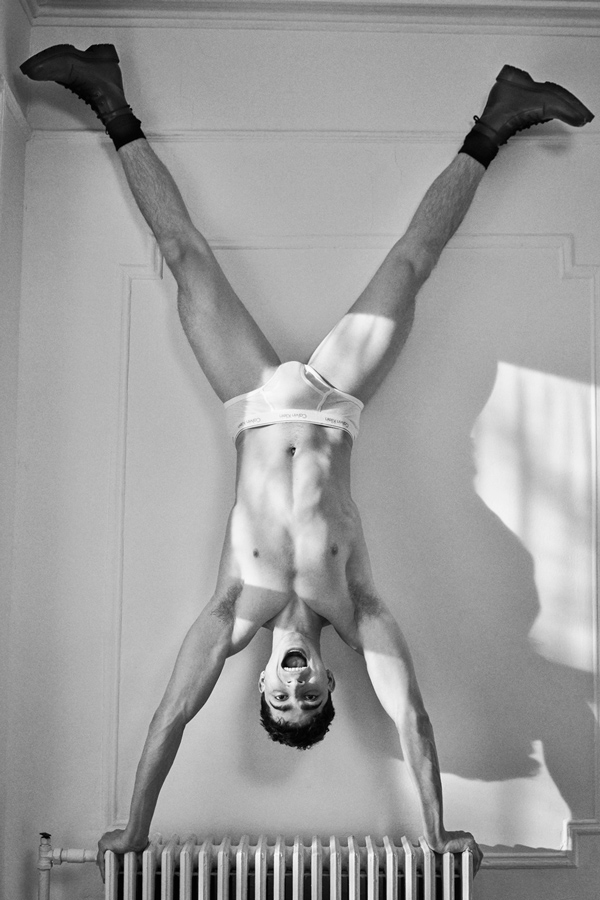

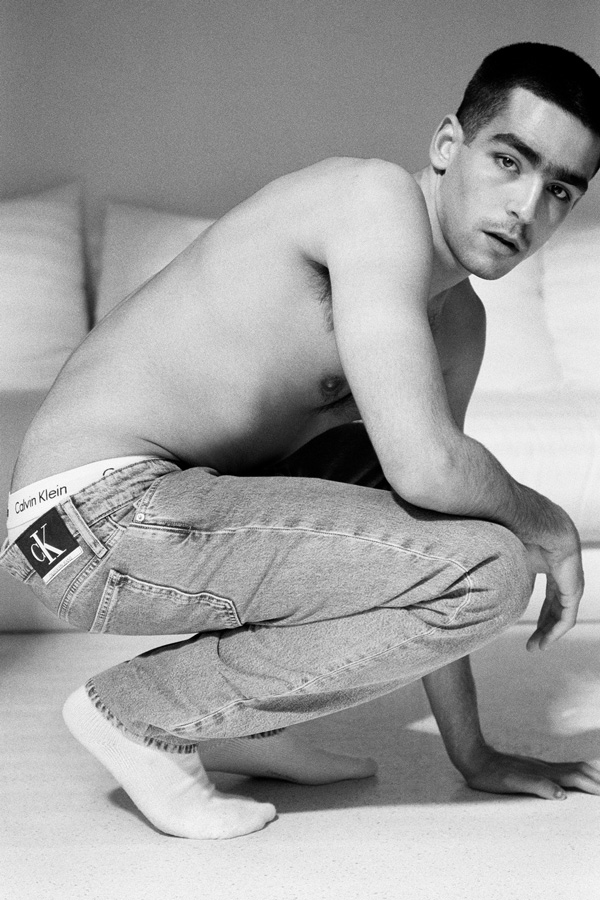

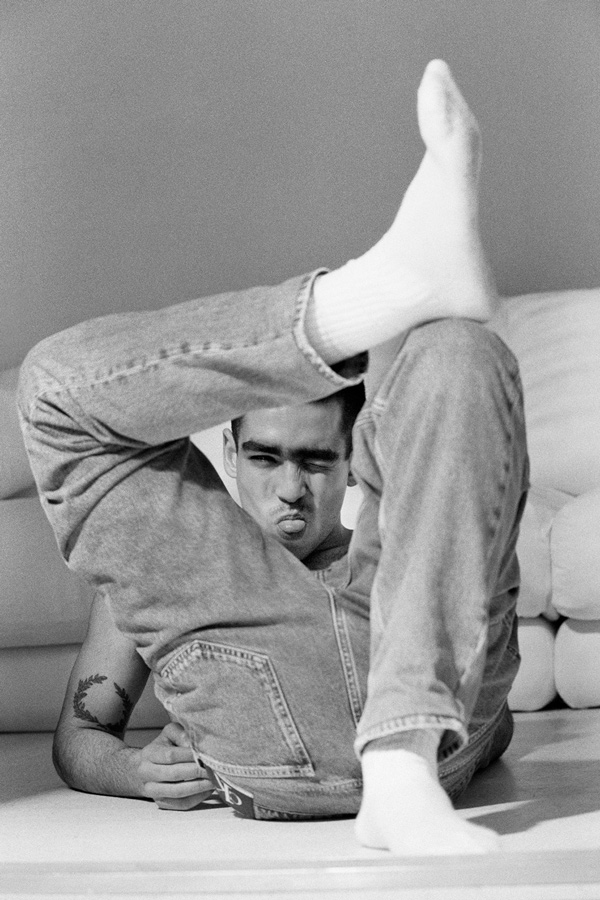

Omar Ayuso (he/him) shot by Gorka Postigo in Madrid

Spanish actor Omar Ayuso, best known for his role as Omar Shanaa on the Netflix series Elite, felt affirmed simply by admitting who he truly was to both himself and to the people around him. In his video, Ayuso admits how scared he was when he first came out to his mother in 2013, “I came out of the closet when I was 15. And to begin with, I told a couple of female friends, but what I remember was when I told my mother. I thought she would be shocked and make some big scene or get really mad… Not at all, quite the opposite.”

“When I could finally be who I was and had nothing to hide, which I can tell you was only in part because I still find it hard today, I felt calm and at peace because you’re no longer living with the fear or anguish that people around you will reject you.”

They say ‘life is about the journey, not the destination,’ and although it would be naive to undermine the freedom that comes with embracing who you always knew yourself to be, in order to truly learn from each other’s experiences, it is also necessary for us to look back on the events that led up to this precise moment.

Along with uplifting the vibrant members of the queer community by celebrating those transformative moments of queer affirmation, Calvin Klein has also reimagined some of its iconic styles in fun Pride-appropriate colourways for its Pride 2021 capsule collection—from Calvin Klein Underwear staples like bralettes and jockstraps and Calvin Klein Jeans pieces like trucker jackets and cropped vests to accessories like bags, hats, and eyewear.

Because the brand knows that actions speak louder than words, it has also announced a two-year partnership with The Trevor Project, the world’s largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organisation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning young people. Through this partnership, Calvin Klein will use its platform to increase the knowledge of The Trevor Project’s essential 24/7 crisis services and other mental health resources to help promote wider inclusion for the LGBTQIA+ community.

In addition, the brand supports ILGA World’s work as the global voice for the LGBTQIA+ rights of those who face discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and/or sex characteristics.

Learn more about the campaign and shop Calvin Klein’s Pride 2021 collection here.

Credits

Featured talent

Arca

Photographed by

Gorka Postigo

Featured talent

Honey Dijon

Photographed by

Matt Lambert

Featured talent

Kai Isaiah-Jamal

Photographed by

Campbell Addy

Featured talent

King Princess

Photographed by

Collier Schorr

Featured talent

Isaac Cole Powell

Photographed by

Ryan McGinley

Featured talent

Raisa Flowers

Photographed by

Ryan McGinley

Featured talent

Samuel de Saboia

Photographed by

Vivi Bacco

Featured talent

Omar Ayuso

Photographed by

Gorka Postigo