Chinese students invent invisibility coat that counteracts invasive AI security cameras

It’s no lie that China has a surveillance problem. I get spooked living in London (the 9th most surveilled city in the world, according to the net), so I’m not sure I’d be able to handle one of China’s mega metropolises. A beautiful country with a rich history—and a relentless hardline authoritarian government. From strict no-COVID policies to forcing its bus drivers to wear emotion-tracking wristbands, China has a tight grip on its citizens. Perhaps this was what encouraged a team of promising students to invent an ‘invisibility’ coat.

The aptly named InvisDefense coat is the brainchild of four Wuhan University graduates, who recently took home the first prize at the China Postgraduate Innovation and Practice Competitions, in part sponsored by Huawei.

How does the InvisDefense coat work?

The professor who oversaw the mysterious cloak project at the school of computer science within Wuhan University, Whang Zeng, told the South China Morning Post that the technology “allows the camera to capture you, but it cannot tell if you are human.” The surveillance systems in China are incredibly thorough when it comes to distinguishing people from inanimate objects, often with a scary level of accuracy.

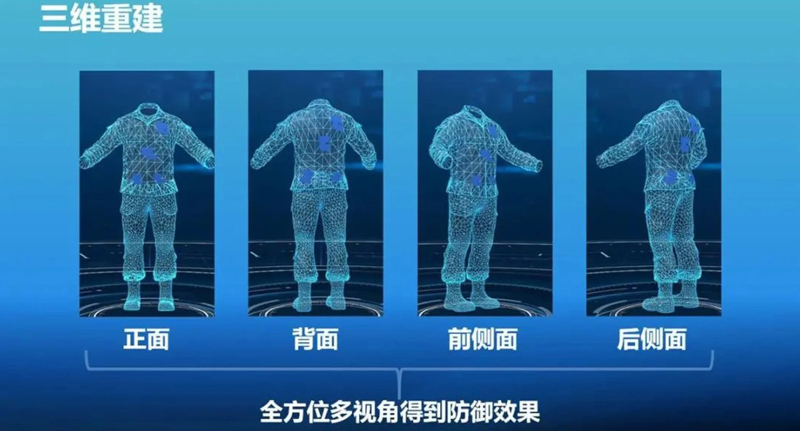

That’s where the ‘invisibility’ coat comes in, with its primary function being to inhibit the surveillance’s ability to accurately detect a human through motion and contour recognition. The garment has a specially designed camouflage pattern on its surface, which helps to interfere with the camera’s AI. When put to the test, the pattern reduced pedestrian detection by 57 per cent.

What about at night-time though? Surveillance cameras in China are also able to use infrared thermal imaging in order to detect heat signatures. To counter this sneaky measure, the cloak is equipped with irregularly shaped temperature modules under its high-tech surface which, in turn, confuses the infrared camera.

One of the main objectives for the students when constructing the jacket was to enable the wearer to be inconspicuous to the human eye as well. Wei Hui, designer of the core algorithm explained that “traditionally, researchers used bright images to interfere with machine vision.” While this approach worked, it often made the wearer a bigger target to those around him, rendering them invisible to the mechanical eyes of surveillance, but not to the organic ones of humans.

This partnership between AI and fashion has been exemplified in the past by clothing brand UNLABELED whose garments do a good job of challenging the machine, but a poor one at not catching the eyes of intrigued passersby as their pieces often feature bright and garish colours.

The Chinese academic team essentially tried to create as inconspicuous a design as possible, using algorithms to help keep the jacket wearable on an everyday basis—while still effective at deterring AI surveillance. To achieve this, they carried out hundreds of preliminary tests over a three-month period to formulate the best pattern.

The team have since shared how excited they are about the future potential of the coat, saying it’s the first on the market of its kind, and that its 57 per cent detection reduction success could grow exponentially in the coming future.

How will the InvisDefence coat impact the future of AI surveillance?

The coat boasts a surprisingly low cost of manufacturing, meaning that the tech’s retail price will sit at a reasonable 500 yuan (£58). The cost of printing the pattern is cheap, and only four heat modules are needed for the camouflage to be effective. But is this a price tag aimed at the everyday consumer hoping to regain a little bit of privacy in their day to day? Unfortunately, this is an unlikely scenario.

The team, who all reside in China, are aware of the power this tech holds, stating that “privacy is exposed under machine vision.” The ethical quandaries these systems impose aside, the students were quick to clarify their position on their invention, stating that the coat has both military and defence applications which could be used to help strengthen security, not weaken it. The project has primarily served to highlight “loopholes” in the Chinese system, said Wei Hui, while also showing the country—and the world—just how cost-effective a personal AI system can be.

AI and surveillance in general are prevalent across the entirety of China and are used in a variety of ways. From identifying waves of citizens as they commute to their jobs to tracking children who’ve stayed up late to play games—it’s a tool the Chinese government favours heavily. Although the InvisDefence coat has shown promise as a countermeasure to the country’s oppressive controls, those responsible attest that its purpose is purely beneficial to the nation, and not a means to stoke the flames of social upheaval.