Chinese teenagers can now use Douyin, China’s TikTok, for only 40 minutes a day

Play time’s over for China’s youth as the country increasingly cracks down on culture and business following President Xi Jinping’s call for a “national rejuvenation.” Joining a three-hour ban on “electronic drugs” (popularly known as video games), is yet another limitation on how the demographic spends their free time.

TikTok on the clock

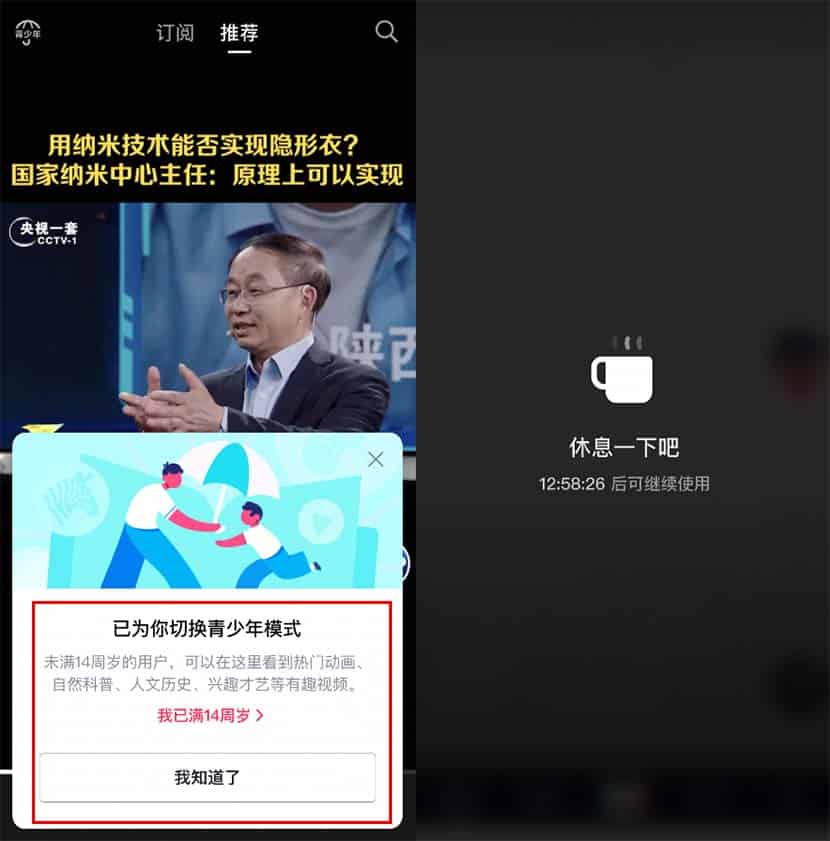

On 18 September, ByteDance, the parent company of Chinese video-sharing app TikTok—known as Douyin—imposed a daily usage limit for those under the age of 14. The new measures not only restrict them to a maximum of 40 minutes spent on the app per day but bans them from accessing it between 10 p.m to 6 a.m.

Called Xiao Qu Xing, which translates to ‘Little Fun Star’, these restrictions are implemented with a built-in feature called ‘teenage mode’. “If you are a real-name registered user under 14 years old, you will automatically find yourself in ‘teenage mode’ upon opening Douyin,” the company wrote on its corporate blog. Apart from the daily usage limits, the mode offers a personalised feed of short video-based educational content including “interesting popular science experiments, exhibitions in museums and galleries, beautiful scenery across the country, explanations of historical knowledge, and so on.” While young users are allowed to ‘like’ these clips, they are banned from sharing them with others or even uploading their own.

The autonomy to adjust the time limit further (from a maximum of 40 minutes) is under parental control. The company also encourages them to help their children complete the ‘real-name’ authentication process—which requests their name, phone number and an official ID—and activate the mode when prompted by the app.

China and the curious case of ‘teenage modes’

In June 2021, the Chinese government added a chapter on “internet protection” to its newly-revised Minor Protection Law, which stated how “providers of online games, livestreams, audio and visual content and social media should implement time management tools, feature restrictions and purchase restrictions for underage users.” Presently, with the government seeking to implement rules on the algorithms tech companies use to recommend videos and other content, top officials and state media are aiming to reduce the amount of time Chinese teenagers spend online in the first place.

Douyin’s teenage mode not only keeps the company in line with this vision but also seeks to add this layer of ‘internet protection’ with its real-name authentication feature. However, according to a commentary in the People’s Daily—the mouthpiece of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—such modes deployed by Chinese internet platforms “to protect teenagers from gaming addiction and inappropriate short videos,” do not go far enough, signalling that tech giants will likely have to do even more to safeguard minors and appease regulators.

“While the youth modes have apparently accumulated a significant number of users, many problems still persist—with some youth modes being criticised by parents as ‘existing in name only’,” the state newspaper mentioned, adding how it can be easily bypassed with simple workarounds.

The article, as noted by South China Morning Post, cited the case of a father in Guangxi who said, “I don’t know how my son came to know the password that I’ve set and he flat-out disabled the youth mode in these mobile games. He even said that some classmates of his have bought hack tips from the internet to bypass the ‘youth mode’.”

While Tencent started leveraging facial recognition to limit the amount of time minors could spend playing games, the technology is far from being the ideal alternative here—given how children have previously cheated the system to set up their own OnlyFans using documents of their older relatives. With Kuaishou (another video-sharing app and Douyin’s major competitor in China) also featuring a teenage mode which is non-mandatory, concerns have been triggered over the possibility of such rules being adopted by companies globally to maintain their share in China.