Danish app iConsent gives users a 24 hour sexual consent contract—really?

You guessed it, the Danish app iConsent does just what its name suggests: it allows users to sign a 24 hour consent contract along with whoever they’d like to have sex with. Now, this may sound both weird and slightly dodgy, but the initiative actually came as a practical answer to a new Danish law requiring provable, explicit consent before a sexual act. But does iConsent’s written contract really stand in the eye of the law?

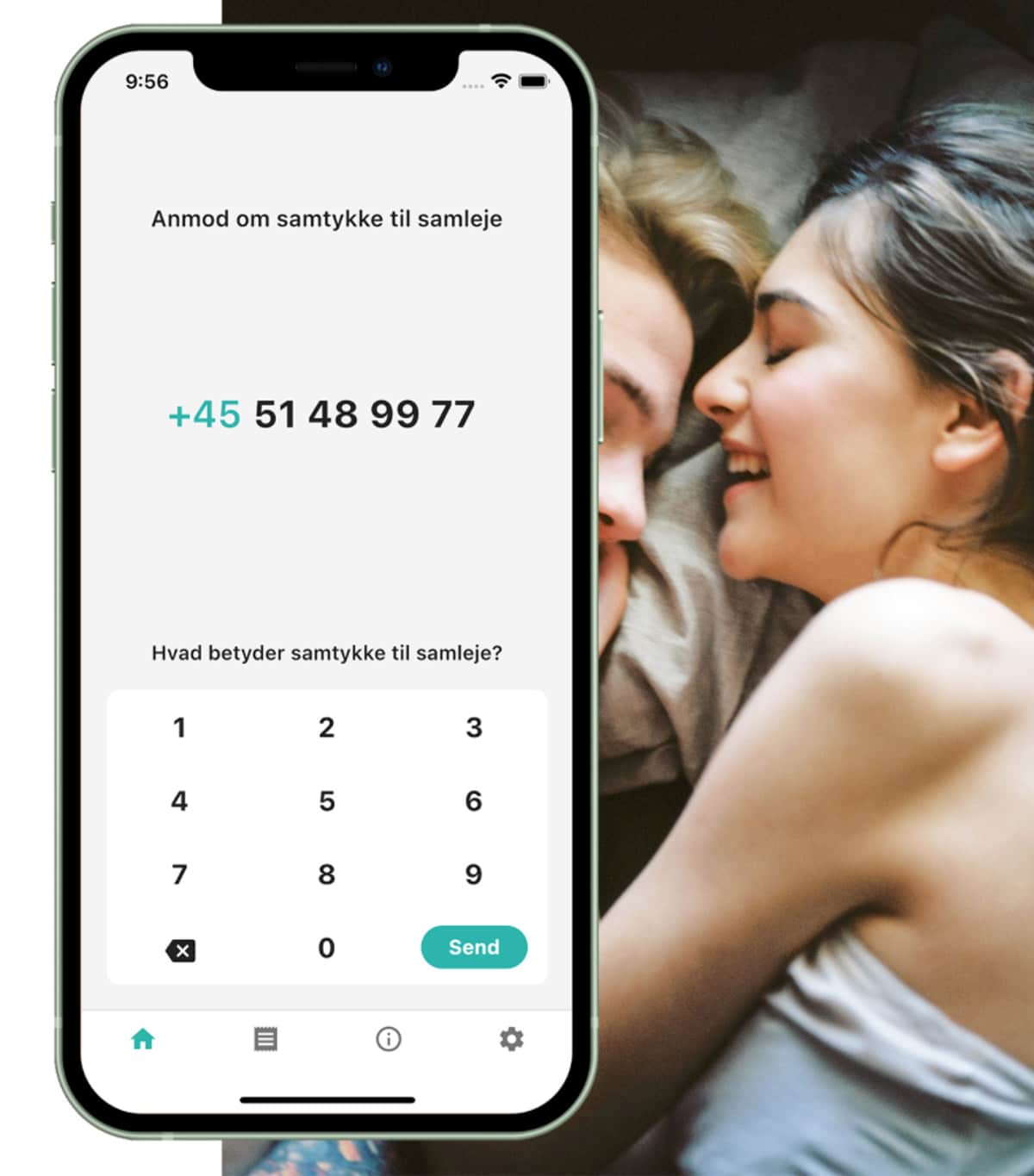

The app’s developers promise users a way to “make digital consent the norm, preventing misunderstanding and abuse.” iConsent connects users via their phone numbers and allows them to complete a transaction authorising sex. This mutual consent ‘token’ is valid for one-time sexual intercourse only and expires after 24 hours.

During this period of time, the app encrypts and stores the digital contract to be recalled later, if needed, as proof of consent. Unsurprisingly, iConsent made headlines in close to no time for its controversial selling point. A commentator at leading Danish daily Politiken said that he thought the app was a sarcastic joke, only to learn later on that the developers were deadly serious.

In Denmark (and now all over the world), reactions towards the app have ranged from “a scandalous misunderstanding” to “pretty nonsensical.” Legal experts have contradicted the app’s developers, saying it is unlikely their consent certificate would stand up in court given the fact that this 24 hour window allows time for people to change their mind.

For many, iConsent is everything but the right way to secure consent. Speaking to The Irish Times, professor Mikkel Flyverbom of the Copenhagen Business School, and a member of Denmark’s data ethics council, said the app was a prime example of modern societies’ “naive belief in technology.” And Flyverbom is not the only one seeing iConsent as a medium perpetuating a “sad view” that will eventually reduce human beings and interactions to data and buttons.

But the app actually resulted as a potential solution to Denmark’s newly introduced law. Following Sweden in 2018, Danish MPs in December 2020, backed a law making sex without explicit consent a criminal offence. Proponents of the new law said it would assist Danish prosecutors who often struggle to prove violence and coercion were used to secure sex.

Earlier, the Danish law required prosecutors to prove that violence was used on someone who was unable to resist unwanted sex in order to legally constitute rape. According to the new law, if both parties do not consent to sex, then it’s considered as rape.

But there’s one unignorable problem with iConsent; the app would not hold in court, as electronic consent doesn’t make it easier to prove that one has not committed rape, as defence lawyer Morten Bjerregaard told International Business Times. In other words, giving written consent to someone at 10 in the morning doesn’t imply that you’ll still be in the same state of mind by 10 at night.

Furthermore, we’ve already witnessed how easy it is for someone with malicious intentions to hack into somebody else’s phone. And what then? Will the contract coming from a specific phone number still count as consent? I certainly hope not.

Sadly, the fact that before being sexual with someone, you need to know if they want to be sexual with you too is not known or followed by everyone. It’s also crucial to be honest with someone about what you want and don’t want to do. But will iConsent truly help spread awareness about the ins and outs of sexual consent or will it dehumanise and unrightfully simplify the complexity of the matter? The answer seems to be in the question itself.