New research shows CRISPR turns normal body fat into energy-burning cells

CRISPR (pronounced crisper) is a technology developed for the purpose of editing genomes, which in turn allows researchers to alter DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) sequences and modify gene function. It has many potential applications, some of which allow scientists to correct genetic defects, treat and prevent the spread of diseases. Promises often linked to the technology have also raised many ethical concerns, understandably. How does CRISPR work, and what has recently been discovered?

How does CRISPR work?

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats Repetitive) is in fact shorthand for ‘CRISPR Cas9’, which are specialised stretches of DNA. The protein being Cas9 is an enzyme that acts like a pair of scissors (molecular scissors), which are capable of cutting certain strands of DNA, therefore modifying them.

The technology was adapted by following natural defense mechanisms of existent bacteria and archaea (which is the domain of single-celled microorganisms). Organisms such as these use CRISPR-derived RNA (ribonucleic acid, a complex compound of high molecular weight that functions in cellular protein synthesis and replaces DNA as a carrier of genetic codes in some viruses) as well as various Cas proteins such as Cas9. This allows these organisms to dodge attacks from harmful viruses or other foreign bodies that harm the good ones. They do so by literally chopping up and destroying the DNA of those unwelcome invaders.

CRISPR is powerful, and potentially ethically problematic, because of its ability to manipulate genes. In other words, it can edit for better, or for worse. One new discovery in particular may be sparking an interest in, we could argue, not only scientists, but the general public, too.

CRISPR’s new discovery

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), about 39 per cent of men and 40 per cent of women are considered overweight in the world. It’s a problem, and that’s a fact. However, besides that, metabolic conditions that are linked to obesity could be treated in a not-so-distant future by removing fat from a person using CRISPR gene editing.

How humans burn body fat

Most fat merely stores energy, and some fat, known as brown and beige fat, burn glucose (a simple sugar and also a component of many carbohydrates) to produce heat, or burn energy. Human adults have plenty of white fat, which are the cells that are filled with lipids that make up fatty deposits, or storage. But we have much smaller reserves of these energy burning and storing brown fat cells.

Humans, or animals for that matter, typically lose brown fat as they age or put on weight (which is also caused by an increase in white fat). Studies have found that brown fat may be stimulated when we are exposed to cold temperatures, however so far, methods of building up or increasing this particular brown fat that burns energy rather than solely stores it within our bodies have not yet been found. Until possibly, now.

CRISPR modifies fat performance in mice

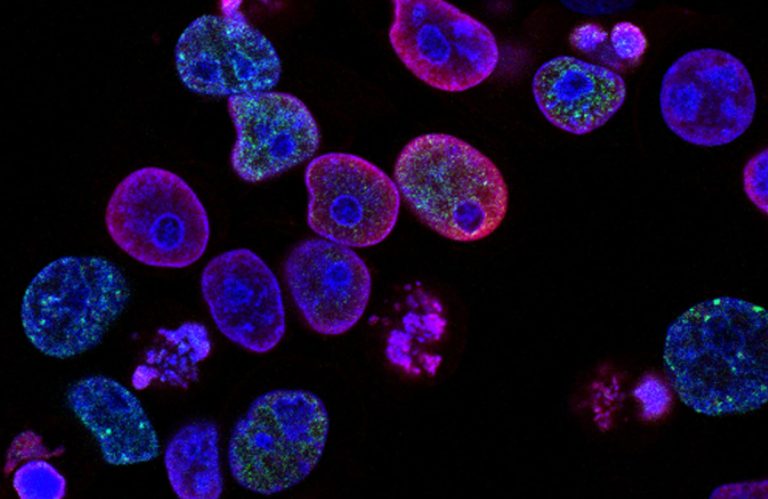

Principal investigator at Harvard University, Yu-Hua Tseng, and her colleagues have made the first attempt at getting around this challenge. The researchers have used the CRISPR gene-editing tool to give human white fat cells, the properties of brown fat, by targeting a gene uniquely expressed in brown fat for a protein called UCP1, which according to Tseng has the function to turn chemical energy into heat. These newly created cells, officially called human brown-like cells, have been named HUMBLE cells.

In furthering the researchers’ study to learn more about how HUMBLE cells function, Tseng and her colleagues transplanted either white fat, brown fat or HUMBLE cells into mice that were bred with a weakened immune system that would reject human tissue. The mice were then fed a high-fat diet.

Over a twelve week period, the mice that were given white fat cells gained weight while Tseng assumed that if they had been typically healthy mice, they would have shown signs of diabetes. The mice transplanted with brown or HUMBLE fat, gained significantly less weight, but also proved to be more sensitive to insulin, which suggests that they may be protected against diabetes all together.

The scientists concluded their study by writing that “This study provides a potential strategy to combat obesity and metabolic syndrome by using CRISPR-engineered HUMBLE cells combined with an autologous cell transfer-based therapy.”

Let’s just hope that, as the study evolves along with CRISPR technology, humans will learn from mistakes that they have made with previous CRISPR research studies.