Meet Captain Beany, the folk hero who has dedicated his life to baked beans

“Password?” a muffled voice asks from behind the door. I’ve arrived at the residence of Captain Beany, a man who has dedicated his life to baked beans—going as far as to transform his council flat into an operational baked bean museum. Taken aback, I reply: “Baked beans?” The door, hanging a blue plaque plastered with the words ‘The Baked Bean Museum of Excellence’, swings open. I’m hit with a luminous wall of orange.

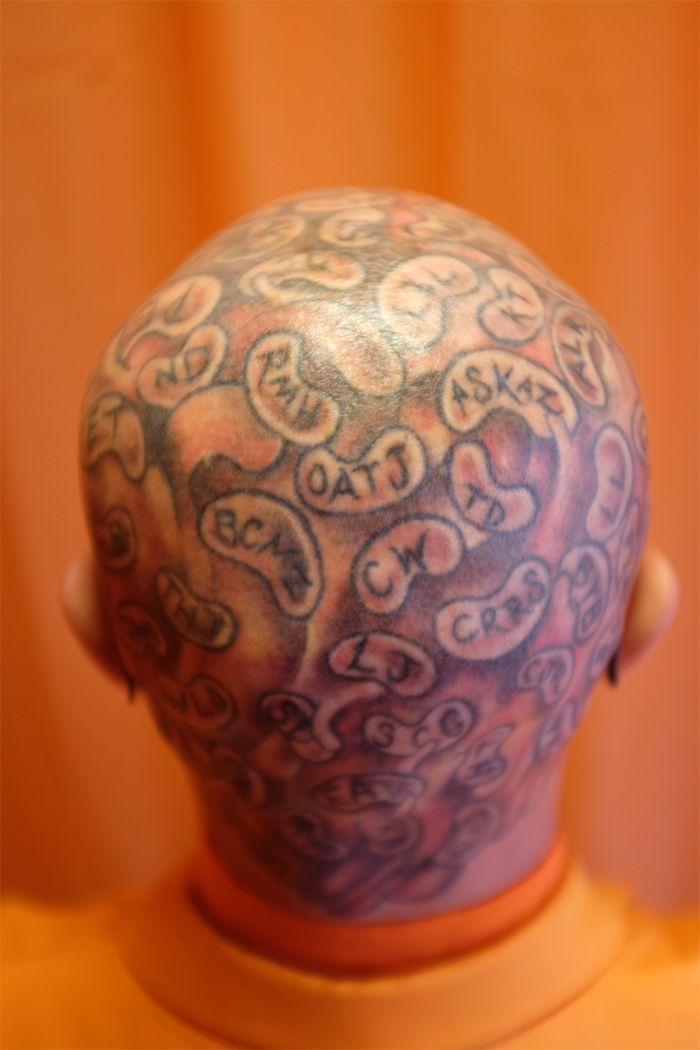

Captain Beany welcomes me into his home dressed in a tangerine suit, tinted glasses and high-heeled boots to match. His head is completely bald and his eyebrows shaven, replaced by tattoos of baked beans where hair once was. It seemed like he had prepared for my arrival—or perhaps this was just his everyday attire.

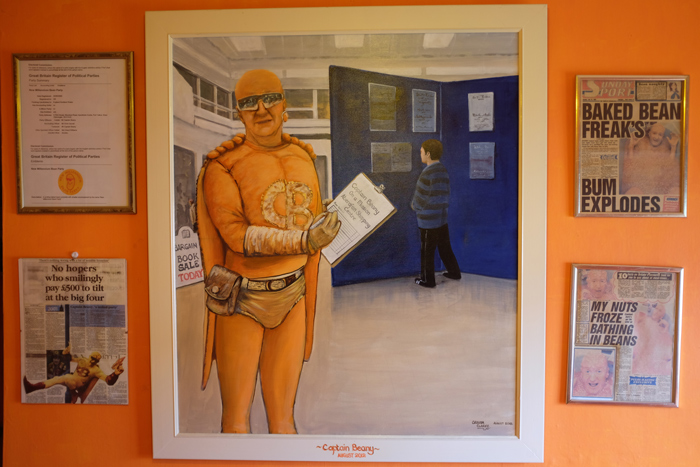

“Take a seat, Jack,” he says as he leads me into his living room. The space is, of course, mind-numbingly orange, littered with artefacts of his past achievements. A shelf running across the length of the wall displays countless trophies, newspaper cuttings and photographs. The wall adjacent hosts a large canvas of Captain Beany himself, akin to a historical renaissance painting.

He clocks my sensory overload as I slump back on the—you guessed it—orange sofa, offering me a cup of tea. “It’s a lot… I could write a book if I had the time,” he adds. Although his eccentric personality may have initially caught me off guard, his warm Welsh hospitality soon has me at ease.

“This museum is full of baked bean artefacts from across the world,” Beany beams, touring me around his flat. “To this day, people donate things to me, and I cherish them.” It’s clear Beany takes great pride in his home—with meticulous attention to detail paid to every object—from the orange toilet brush to the Heinz branded toaster.

His spare room, however, is the star of the show: hosting a collection of early 1990s bean memorabilia, countless limited edition Heinz cans and even his own baked bean-themed coffin—with the phrase ‘Rest In Beans’ etched into the wood.

The Baked Bean Museum of Excellence sits at the epicentre of Port Talbot, a small post-industrial town in South Wales. The town’s mammoth local steelworks, which is one of the largest in Europe, protrude against the horizon. “I was brought up here and to this day embellish this town. It’s a lovely, tight-knit community,” he says.

“The Museum now has relevance, it has a special connotation—it’s the highest rated attraction on Tripadvisor in the local area,” Beany continues. “For me, it’s like a theatre: I’m the main actor and you are the audience. I love nothing more than entertaining people from all walks of life. I never know who’s going to walk through that front door, but I make it my mission to accommodate them and leave them full of beans.”

Captain Beany—formally known as Barry Kirk before legally changing his name back in 1991—found his life’s calling for beans, and with it, his new identity, in the 1980s. “I’d always love drama, dressing up and stuff like that,” he recalls. “At the time, I was working for BP and wanted to put something back into the community.”

“I was walking down the street and saw an album cover of Roger Daltrey in a charity shop, he was in a bath of baked beans and I thought to myself ‘If it’s good enough for Roger, it’s good enough for me’.” Unknown to Beany at the time, this was one of the most formative moments of his life—unearthing his dedication (and obsession) to baked beans, all the while raising money for charitable causes.

Ironically, our meeting was 36 years to the day of his first baked bean stunt—spending 100 hours in a bath of baked beans to raise money for a local charity that helps children with special needs. “You can’t really rehearse that kind of thing,” he notes, recalling the moment in September 1986 when he first stepped into the bean-filled bath.

“You literally have to go in hell-bent on spending 100 hours in a bath of beans. I didn’t know what to expect, I just went for it. I managed to stick it out for the whole 100 hours. When I got out I was shattered. My mother grabbed me and said, ‘Son, don’t try anything like that again…’”

That advice, obviously, fell on deaf ears. Throughout the decades, Beany has since dipped his fingers into countless charitable events: from running marathons to pushing a can of beans for a mile with just his nose. He’s also had a notable political career too, running in a number of local and national elections across Wales since 1990.

“I thought it was time these politicians were taken down a peg or two… In 2015, I stood for Port Talbot in the local elections and managed to beat UKIP,” he continues, bellowing out with laughter. “We beat UKIP! The person standing for them was so embarrassed he didn’t even turn up to stand next to me.”

The tattooed beans covering his head glisten under the sun which peeks through the window. When questioned, I’m surprised to find they’re not just there for show but tell a deeper story about Port Talbot’s close-knit community and Beany’s abundant altruism.

“These beans have the initials of everyone who donated towards a local girl called Marlie-Grace Roberts to have a life-changing operation,” he remarks. “She has cerebral palsy, she was only four years old at the time and we pulled together, as a town, to raise £40,000.”

“I thought I’d do my bit by getting 60 baked beans tattooed on my head and offering the local community to sponsor the cause by spending £60 to have their initials on each bean. In the end, it raised £3,600. She had the operation and to this day she’s walking now. I guess there’s a price on my head after all,” he laughs, leaning forward to point towards the bean tattoo with the initials ‘MGR’ on the centre of his forehead.

It’s clear Beany is dedicated to not just baked beans but expressing the message that it’s okay to be yourself. “

He shows me the palm of his left hand and points towards the creases. “In life, I could’ve gone this way and lived a normal life,” he says while tracing his right index finger up towards his thumb. “I might’ve been married, I would’ve been settling down—but obviously, it went offshoot,” he chuckles, this time more diminished than before, tracing his index finger up another crease.

“Perhaps in a parallel universe, there would be a Barry Kirk living a normal life. But in terms of my legacy, I believe I was meant to be this persona, this character, until the end of my days. To be honest with you, I don’t have time for relationships,” Beany continues, letting out a brief sigh and eyeing the ground. “I’ve had encounters with tins of beans in a past life, of course, but I’m still very much a bachelor.”

He goes on to note how his parents have since passed away and his brother now lives in Scotland, where he works for the NHS. “We’re like chalk and cheese—he’s a state registered nurse. He knows me, I’m not completely mad but I am eccentric. He always embellishes the fact that I’m like this. Port Talbot is my family too—that’s what I love to say. The odd thousand people living around this town are my neighbours and my family.”

While leaving, I stopped to take a photograph outside Beany’s flat when cheers were heard from neighbours across the street as the bean enthusiast’s bright orange suit juxtaposed against the pebbledash. I arrived at the Baked Bean Museum of Excellence expecting a man with a questionable obsession with classic (but rather bland) British cuisine. I left with a deeper appreciation for Beany as a person, his altruism and his commitment to his community. It was clear he loved Port Talbot, but equally, Port Talbot loved him back.