TikToker designs controversial ‘euthanasia boat ride’ which plummets passengers to death

Euthanasia, which is the act of intentionally ending a person’s life with the aim of alleviating great pain or suffering, is a highly controversial topic that is continuously debated—especially given that its legitimacy and legality differ between countries. In Switzerland, for example, while active euthanasia—the act of administering a lethal injection to someone who demands it—remains illegal, supplying the means for committing suicide is legal, as long as the infliction is performed by the one wishing to die. This led the country to legalise a new way of self-infliction by assisted suicide in December 2021 in the form of the Sarco suicide pod, a 3D-printed portable coffin-like capsule with windows.

More recently, however, the discourse surrounding euthanasia has resurfaced, on TikTok this time, after content creator @sm.coasters shared a video of a ‘one way only’ boat ride imagined to help those wanting to end their lives to do so in a “totally human way.”

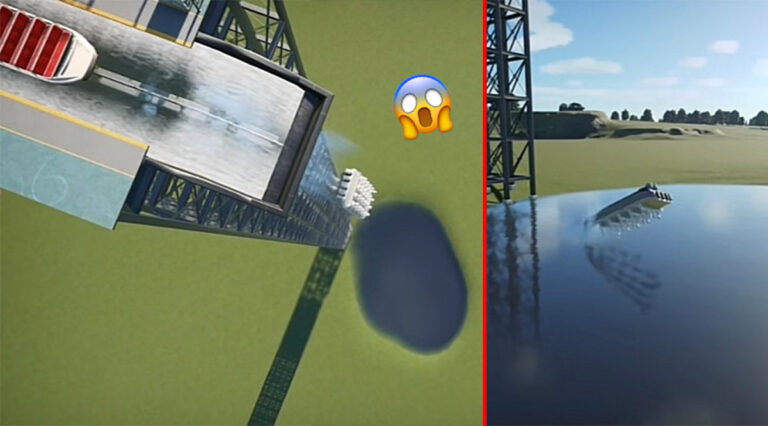

The account regularly shares mock-ups of interesting yet awfully sinister designs for roller coasters and rides. The difference with the viral ride pictured below, which currently has 6.6 million views on the platform, is that it can only be experienced once…

In the viral video, a floating carriage can be seen sitting at the top of a huge structure—only to be nudged over the edge and fall a terribly long way down into what appears to be a pool at the bottom. Upon landing, the carriage is supposed to bounce up into the air before touching down back in the water, undamaged.

As you can expect from a video with so many views, the clip’s comment section is home to many users joking about the morbid invention. One person wrote, “Knowing my luck the boat won’t land the right way up and I’d survive.” Another said, “Yep, that would do it.”

@sm.coasters Boat ride euthanasia - totally humane way to go

♬ original sound - SM.Coasters

Believe it or not, this is not the first time a ‘fun’ concept has been conceived for euthanasia. In 2021, another video made the rounds on TikTok of a journey to death designed by Lithuanian artist Julijonas Urbonas back in 2016. Named the ‘Euthanasia Coster’, the ride was reshared on the gen Z-first platform by TikToker @lukedavidson_ where he explained a bit more about the invention.

Imagined as a single-seated joy ride that lifts the passenger 500 metres up in the air, it would then send them swooping down along seven loop-the-loops at a deadly speed. Reaching 100 metres per second, the speed would induce a euphoric sensation before “extreme G-force” would kill the person riding it.

“Your blood is rushed to your lower extremities so there is a lack of blood in your brain, so your brain starts to suffocate. When your brain starts to suffocate, people become euphoric. Usually pilots experience such extreme forces for just a few seconds, but riders in the rollercoaster experience it for one minute and nobody has experienced this for such a long time,” Urbonas said while presenting the design at the HUMAN+ exhibition at Trinity College in Dublin. He concluded that such a way of assisted suicide introduces the element of ritual to death which has been “medicalised, secularised, sterilised.”

@lukedavidson_ You Can Only Ride This Roller Coaster Once #facts

♬ Paris - Else

Needless to say, Urbonas’ ride never made it past its prototype phase. Whether the latest euthanasia boat ride will witness the same fate or not remains to be seen.