Social media witch hunts: Are you advocating for social justice or are you just a bully?

If you have existed on the internet long enough, you have definitely witnessed someone being cancelled by now. It has become such a common occurrence and presence in our daily online lives that a lot of us have become desensitised to how normalised things like doxxing, harassment, and new-age internet ‘witch hunts’ are.

We live in a world where information travels faster than ever, where thousands of strangers get to share the same online spaces, and where there is always a possibility that something you share online might be seen by millions. While of course, this has hundreds of benefits, it can also lead to a tidal wave of hatred.

You might have heard of the term ‘witch hunts’—in the olden days, there was a time period where, according to some historians, between 30,000 and 60,000 people (predominantly women) were killed as a result of being accused of witchcraft. Typically, a group of people would come together and form a ‘mob’. Some individuals often harboured fears of being accused themselves. Consequentially, they would conform to the beliefs of a larger group, or ‘mob’, and actively participate in the act of accusing others and joining in on those said witch hunts. In some cases, this could even extend to public shaming and executions.

In today’s society, this term is often used to describe something else: a phenomenon in which ‘mob psychology’ and various scandals on the internet assemble thousands of internet users into targeting individuals for their views or actions. Oftentimes, this can result in the target’s personal information being revealed without consent, doxxing, as well as the attempt to involve their employer, family, and friends.

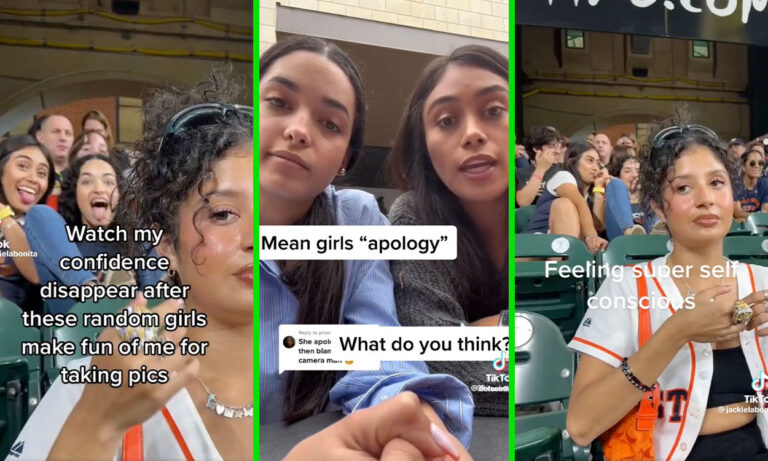

Most recently, you might have seen this event blow up all over TikTok and Twitter. Influencer Jackie La Bonita went to a baseball game and posted a now-deleted video showing two women in the background flipping off the camera and making fun of the content creator, captioning the video, “Watch my confidence disappear after these random girls make fun of me for taking pics,” before adding “please be nice #meangirls.”

yeah ain’t nobody gon survive if that shit happens to me pic.twitter.com/UGOv8GbjT9

— mia 𐐪𐑂 (@cupid4joon) April 22, 2023

In typical internet fashion, the video went insanely viral, and received millions of views, as well as lots of comments and stitches on TikTok. Everyone had something to say, and even Cardi B retweeted it, captioning it, “I would put that ring to use.” This led to the whole situation escalating out of control in something a lot more sinister. Hundreds of people across social media made it a mission to track these girls down and reveal their identities, including intimate details about their lives and locations—aka, doxxing them.

I would of put that ring to use https://t.co/4CWhwtZqBI

— Cardi B (@iamcardib) April 23, 2023

Eventually, everything was out—their full names, the identities of their family members, one of the girls’ ex-partners, photographs of them from high school, their alleged workplaces, you name it. The doxxers even made it their mission to leave hundreds of fake comments on the Google reviews page of one of the girls’ alleged workplace, urging her place of employment to fire her in the name of justice, accountability, and of course, “#bekind.”

Now, was the behaviour of said “mean girls” quite callous? Yes, and the way in which their actions were depicted in the video did come across as rude and unnecessary. However, the real problem here is that we were just shown a 50-second clip without any context whatsoever, other than La Bonita’s perception of the events and her side of the story. And that short video was reason enough for hundreds, if not thousands of people, to take time out of their day and try to ruin the livelihoods of the “mean girls,” and compromise their safety and their livelihoods.

Both girls have since come out with a video of their own explaining their side of the story, claiming that they felt uncomfortable that they were being recorded by a man (the man in question was the person taking photos and videos of La Bonita in the first place) for over five minutes or ten minutes, and that the flipping off was not aimed at the influencer, but at the camera itself.

They further explained that they have both received death threats and had their home addresses revealed. “I’m not justifying her behaviour, I’m not justifying ours but what is happening to us, coming from millions of people is honestly very scary,” one of them said in the video.

@dohwatson What do you guys think?#jackielabonita #lizandalondra

♬ original sound - Doh Watson

Now, this “mean girls” baseball gamegate is just one example, but people on the internet get doxxed all the time, as a result of the cancel culture we have all created in recent years. Sometimes, it’s for minor cases like this, and in others, doxxing can happen as a result of somebody’s much more severe and problematic actions.

Now, I am not saying that people should not be called out—justice is important, and accountability is something we should always advocate for as a society. But is the best way to get justice by joining a modern-day witch hunt? Should we justify doxxing as an appropriate form of punishment, and is it really the best way to create actual change? The digital world we operate in often doesn’t have any rules, but sometimes boundaries are necessary.

@gaggle_of_ferrets #duet with @dottoresmunch in baffked by the audacity the internet has

♬ original sound - Viv

As clinical psychologist Dr. Robert T. Muller wrote in a piece for Psychology Today, “When a victim becomes a target by an online mob, not only can they suffer physically, but they can also face psychological trauma.”

He went on to add, “A study on doxxing revealed that when any form of personal information is spread publicly, the victim feels depressed, anxious, and stressed. Another study surveyed 1,963 middle-school students in the United States on their experiences with online harassment. Whether the youth in this study had been bullied or had acted as bullies themselves, they showed an increased risk for suicidal ideation.”

While it may be obvious that being the target of an internet witch hunt will have serious consequences on one’s life, the bigger question is why do we engage in these behaviours as an internet society in the first place?

Well, turns out there are a lot of reasons that can explain our online society’s weird thirst for cancel culture, and with it, an odd subcategory of online social justice. In some cases, it can be argued that spending so much time online, and having so many heated discussions on a weekly, if not daily, basis is blurring our perceptions of reality. Thus, we end up normalising behaviours behind our screens that we wouldn’t necessarily engage in real life.

Take the baseball game incident as an example. La Bonita did not confront the girls IRL, but rather indirectly did so online through her post, and at a distance. In a similar way, all those weighing in their opinions were able to do so behind a screen and a keyboard, as opposed to having to defend the content creator in real life.

It can feel a lot easier to seek ‘justice’ and morality from a distance, which can explain why so much of this discourse exists purely online. A lot of netizens who engage in these behaviours are also doing so anonymously, making them unlikely to face much accountability for extreme behaviours such as harassing or doxxing someone.

In other cases, a lot of those engaging are trolls themselves, and may not be doing so for the sake of justice, but rather, for the pure sake of internet trolling. We’re all aware of how toxic social media can be when people allow online narratives and opinions to become more important than interactions that’re occurring in the real world.

Some psychologists suggest that it is a lot more complicated than that, and that actually, we engage in social media witch hunts because of a concept called ‘mob psychology’, where it is argued that individuals can be influenced by their peers to think in a certain way. Some studies have found that a group of like-minded people, with similar interests, sets of beliefs, and morals can become more polarised as a collective, because when they see their opinions reflected in others, those opinions then become strengthened. It’s something that frequently occurs within online conspiracy theories and cults as well as within wider mainstream internet conversations.

Thus, it might seem that if we all observe something that appears morally wrong, and we all agree and discuss this, we might feel a lot more confident and assertive in our actions to fix said moral wrongs.

But there is certainly a way to have these conversations and discuss things we do not agree with—and things that definitely need to be called out—without jeopardising people’s safety. If you want to address bad behaviour on the internet, go ahead, but do it in a way that is productive and helpful to the greater cause. Always ask yourself: are you combating bullying, or are you just becoming a bully yourself?