Behind the Instagram account posting from inside a life-threatening refugee camp

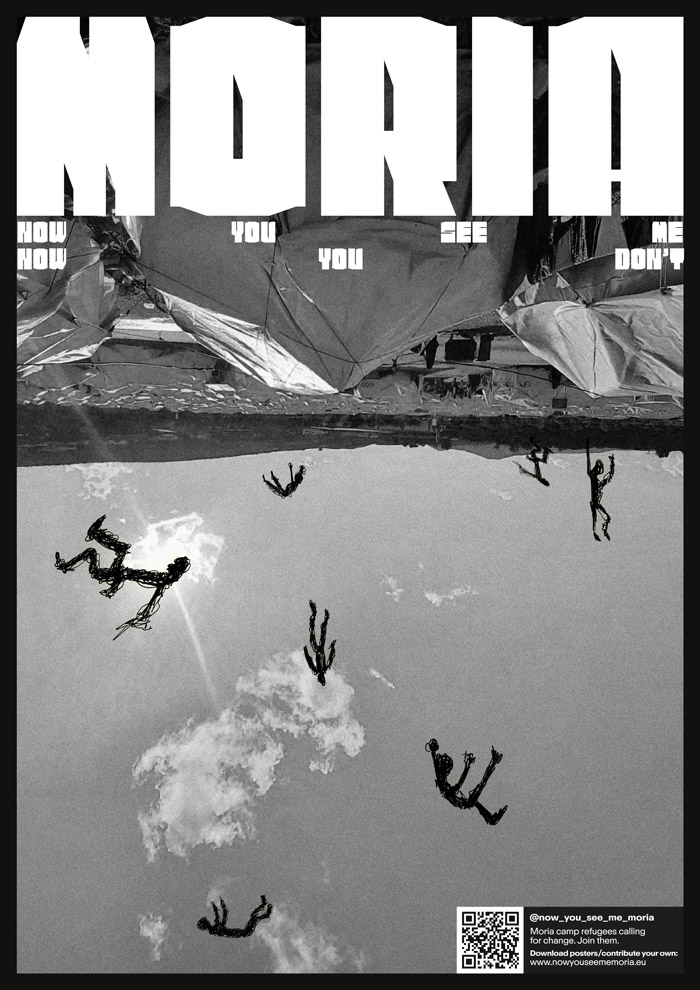

‘A picture is worth a thousand words’. I know, it’s a cliché, but bear with me—photography is an incredibly powerful tool. It can expand our knowledge, our empathy for strangers and, ultimately, tell a story. This story will leave you at a loss for words: angry and yearning for change. Enter @Now_You_See_Me_Moria, an Instagram page, turned photography collective, turned into a global movement—telling the stories of refugees living in life-threatening conditions through the lens of the refugees themselves.

Now You See Me Moria was started at a point in time where Amsterdam-based photo editor Noemi was going through heartbreak in July 2020. “I just felt pain, a strong pain that was gouging through my whole body, physical pain,” she wrote on the website. One night, she was struggling to sleep and resorted to Facebook to numb the boredom. Among the timeline, she stumbled across the work of photographer Amir, a 21-year-old Afghan refugee capturing his experience living in the conditions of the Moria refugee camp in Greece.

“At that moment, when I saw his photos, I realised he was trying to explain what was happening in the camp,” Noemi told me. “Europe was not interested at all—we were all concerned with our own issues [not pay attention to what was happening there]. I couldn’t find any new information about the situation in the camp.”

A raw, unfiltered documentation

“I could see that he was sharing photos within his small bubble on Facebook,” Noemi continued. “I decided to contact him. I thought my knowledge of photography could help him bring those photos outside of his bubble.” She noted how the images Amir created were documentation of the struggles refugees in the Moria camp were facing—essentially, the images cut through the noise—producing a raw, unfiltered portrayal of life in the refugee camp through the eyes of the people experiencing it. “You don’t have to become a photographer or have a [good] camera. To me, the power of the photos was precisely in that.”

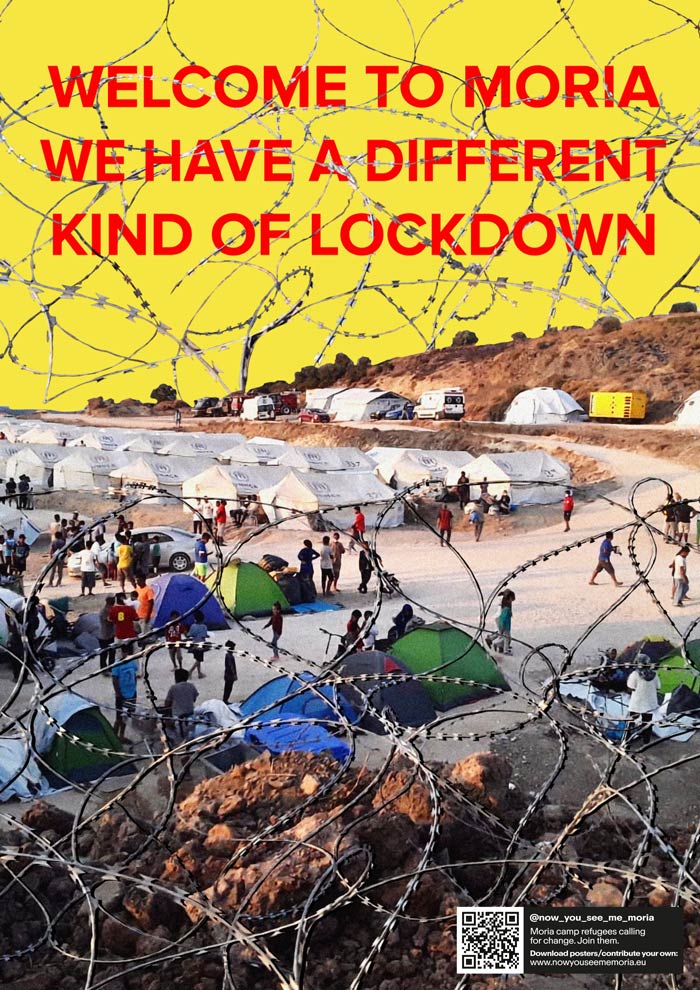

Noemi highlighted that she decided to use Instagram as a platform to raise awareness. It was “free, fast and would give us the visibility we were trying to reach.” However, after five weeks of working on the platform, there was a fire in the camp. “Suddenly, 20,000 people were displaced,” she said, “people were sleeping on the streets without food, without anywhere to go. They were even forming demonstrations to protest.”

She explained that in response to the fire, the refugees were promised another replacement camp with decent living conditions, “which was obviously a lie.” She added, “That’s the worst thing you can say to someone who’s seeking safety. Obviously, all of the refugees went inside, apart from the few who were relocated to other countries.” The camps have notoriously unfit living conditions. The Guardian described the Moria camp as “a place of violence, deprivation, suffering and despair.” Noemi highlighted how the uncertainty of the camp’s future—and when, if ever, the refugees would escape such conditions has led “children to commit suicide, pregnant women to commit suicide, due to the daily emotional stress of not knowing when the situation will change.”

By this point, the small project—initially formed from an insomnia-induced Facebook scroll—was slowly growing into a collective. Qutaeba from Syria, living with his two daughters, and Ali, a 23-year old from Afghanistan, joined the bid to document the conditions of the Moria camp. Noemi added, “This was a really important moment. The new camp was closed meaning journalists and photographers were not allowed inside. They were the only ones really showing what’s happening inside the camp.”

Sadly, a large chunk of Western media has the tendency to paint refugees in a negative light: a danger to society, terrorism, a burden on our public services… you get the idea. This is, obviously, fabricated but it doesn’t stop those with ill intent from pushing that narrative. After all, fear sells—and papers have to make money. Well, that’s one of the many excuses the mainstream press would give in vilifying and dehumanising innocent people fleeing war-torn countries.

Now You See Me Moria is pushing the narrative in the right direction. The narrative that refugees are humans, just like you and me—not threats to society but innocent people escaping war, only to be held in dangerous and life-threatening conditions. Noemi explains, “The more you see the images the more you seem to know them. Not just the dramatic moments like the fire but also images of their daily life. When you see them cooking or playing with animals, you see how similar they are. Those are the boring moments you will never see in the media—they allow people to connect with compassion and empathy. It will make them act and not accept the situation anymore.”

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

The Valentine campaign: from Berlin to Seoul

“At the start of the project, many people didn’t like the situation but didn’t think they could or know how to change it. What we wanted to do was change this mindset. Show that there is something you can do, even if it’s small.” Noemi continued.

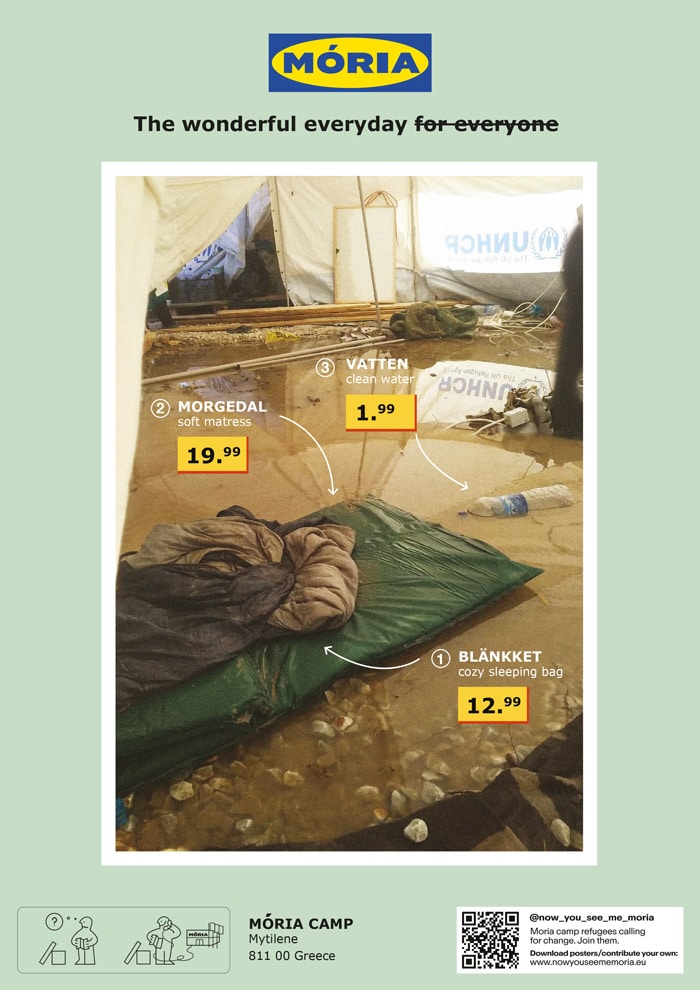

The idea of a campaign was formed, an international movement of graphic designers who would repurpose images taken by those inside the camp into posters, plastering them across many cities to raise awareness. “We started this crazy and surreal idea to be involved with all 27 countries. We knew it would require a lot of infrastructure and money to do that but when we sent out an open call, we received an overwhelming response. Suddenly, over 500 graphic designers across the globe were onboard. It was something really beautiful. In less than four weeks, we had created the Valentine campaign.”

Noemi describes the Valentine campaign as going beyond “just one day—it was like the starting point” of the movement and community behind it. The date chosen was for both pragmatic and symbolic reasons. First and foremost, the situation in the camp was urgent—people were suffering and global attention was needed. Secondly, Valentine’s day is symbolic, as Noemi explained: “It’s a typical couple’s day. We wanted to draw attention to those who had lost the love of their lives due to these immigration policies.”

“It’s our goal to give this visibility—to change the public discourse. The media paints refugees and migrants as a threat, something that we need to protect ourselves from with fences and walls. It’s not true but if you don’t have experiences with refugees, the only way to know about them is through the media. If the media portrays them as dangerous, of course many people will be fearful.”

The demands of the campaign are clear. Noemi stressed the importance of self-representation when forming the demands, to listen to the voices of people actually living in the camp’s conditions instead of people outside speaking for the community. She said, “At first we thought we could push for a change in the conditions of the camp but after discussion with people inside, we realised change is not possible.” The project is pushing for an immediate evacuation of all refugees in the camp to protect their human rights. Noemi argued that they should be relocated to European cities that have expressed solidarity and are willing to welcome them. “Instead of the 250 million euros being sent from the EU to Greece to set up five new prisons, that money should go to the cities which support the refugees so that they can happily integrate and function in society.”