NASA is planning to replace the ISS with commercial space stations by 2030

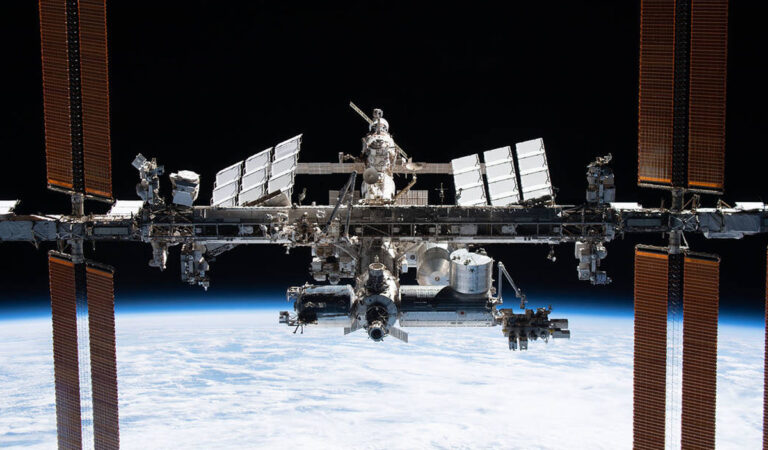

It’s been 23 years since humans put the largest single structure, also known as the International Space Station (ISS), into space. Orbiting 250 miles above our home planet, the world-class lab has hosted more than 200 astronauts and cosmonauts—conducting a plethora of otherworldly research projects since 2 November 2000. Some of the more peculiar guests aboard the station have also included barbie dolls, glow-in-the-dark baby squids, water bears and The Blob. Heck, they’ve even been aging wine and human semen up there. Separately, of course.

However, all good things must come to an end and the ISS has been showing due signs of aging—with air leaks, near collisions and software glitches throwing the station off-course momentarily. In short, retirement is inevitable and NASA is already looking for a headstart into the replacement process. So what comes after the ISS? Are plans for another multinational construction project underway as we speak?

According to a new report by NASA’s auditing body, the Office of Audits, the agency is committed to replacing the ISS with one or more commercial space stations upon retirement. Yes Bezos, NASA is looking at innovations like your “mixed-use business park” as the next ISS clone—ultimately handing off human occupation of on-orbit science facilities to private companies.

Announcing #OrbitalReef - a commercial space station transforming human space travel and opening access to new markets. Our team developing the premier commercial destination in low Earth orbit: @BlueOrigin @SierraSpaceCo @BoeingSpace @RedwireSpace @ASU https://t.co/PP4wxrfkF3 pic.twitter.com/qJDdYg7BSv

— Orbital Reef (@OrbitalReef) October 25, 2021

Although the ISS was just three years shy of its original retirement in 2024, the Senate passed a NASA authorization bill last year that would essentially extend this date to 2030. The new audit report, however, highlights how this pushback won’t be cheap. “The ISS costs about $3 billion a year, roughly a third of NASA’s annual human space flight budget,” the report read. A potential six-year extension means additional system upgrades and maintenance. While overall ISS operation and upkeep costs remained steady at about $1.1 billion a year between 2016 to 2020, it rose by 35 per cent (approximately $169 million) in the same 5-year period—primarily due to the upgrades. Given these figures, the transition of operational responsibilities to private companies makes sense.

Why do we need a commercial clone of the ISS in the first place?

Apart from detailing the current costs of the ISS, the audit report explained the need for research facilities in low-Earth orbit. Missions like Artemis, aimed at returning humans to the Moon and ultimately landing astronauts on Mars, would not be feasible without outposts that can double up as test beds for prolonged human exposure in space. The ISS and its eventual replacement will also grant the establishment a permanent presence in space and speed up our eventual plans for doomsday. “As long as humans intend to travel in space, NASA expects research and testing will be needed in the microgravity environment of low-Earth orbit,” the report added.

This is not the first time the agency has hinted at the commercialisation of the ISS either. Back in July 2021, NASA solicited industry proposals for what it has termed “commercial LEO destinations”—in the search of privately owned and operated space stations as potential replacements. Roughly a month later, the space agency received dozens of proposals to its call out. “It was a really diverse set of companies that we got proposals from: small, large, startups, more established,” Misty Snopkowski, the executive for NASA’s Commercial LEO Development Program told Inverse in September.

Hoping to publish a list of service requirements for commercial stations by the spring of 2022, the agency is also preparing to award up to four contracts (worth a total of $400 million) for the first phase of the program. “We want to be able to have these high-level requirements for industry so that they can come up with their best innovative solutions to meet our needs,” Snopkowski continued.

While the executive could not comment on the details, Inverse noted how the proposals could include players such as Axiom Space and Bigelow Aerospace. While the former already has a NASA contract to build modules for the ISS, the latter manufactures compact, inflatable space station modules capable of expanding up to 5,000 cubic meters once in orbit. Boeing, Lockheed Martin, SpaceX and our beloved Orbital Reef by Bezos are also potential ones on the list. According to Laura Seward Forczyk, founder of the space consulting firm Astralytical, there’s no need for these commercial companies to outright duplicate the ISS either.

For instance, the ISS has been bustling with activity for more than 20 years but such commercial space stations may or may not be continuously inhabited. “It might be that commercial companies have different niches that they want to fulfill and they find different demand for those,” Forczyk said. Since NASA is laser focused on finding an outlet for the experiments in the pursuit of further space travel, the agency will simply be buying the services they need from privately-owned companies. “NASA doesn’t need to have access to a commercial ISS clone to do those experiments,” Inverse concluded. Simply put, the space agency will be yet another customer caught up in the space race. For the betterment of humanity, of course.

What does the future look like without the ISS?

According to the audit report, NASA hopes to see a fully-operational commercial station by 2028—giving the agency a two-year overlap before the anticipated retirement and eventual deorbiting of the ISS. Getting a commercial station up and running won’t be easy either. The report identified challenges that included “limited market demand, inadequate funding, unreliable cost estimates, and still-evolving requirements.”

The decision also comes at a time when several private companies are facing a shortage of liquid oxygen, which rockets require to blast into orbit. Coincidentally, Elon Musk himself warned SpaceX employees about a “genuine risk of bankruptcy” if the company could not get Starship flights running once every two weeks in 2022. Consisting of a fully reusable transportation system that is designed to both carry satellites and other technology to low-Earth orbit and beyond, the rocket is an essential part of SpaceX’s Starship project. “If all goes according to plan, Starship will also carry humans to the moon and, eventually, to Mars,” Newsweek reported on the matter. Advising employees to work over the weekend, Musk further admitted his intention to spend the holidays on the Raptor production line.

If a severe global recession were to dry up capital availability / liquidity while SpaceX was losing billions on Starlink & Starship, then bankruptcy, while still unlikely, is not impossible.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) November 30, 2021

GM & Chrysler went BK last recession.

“Only the paranoid survive.” – Grove

The list of challenges doesn’t end there. While NASA hopes for commercial stations to take over the ISS as it nears the end of its tenure, China has already launched plans of building its own space station. Given the fact that NASA is prohibited from engaging in bilateral activities with China, the move by the latter country is more competitive than collaborative.

“Unfortunately, I believe we’re in a space race with China,” said NASA administrator Bill Nelson in a panel at the 36th Space Symposium held in August 2021. “I’m speaking on behalf of the United States, for China to be a partner. I’d like China to do with us as a military adversary, like Russia has done… I would like to try to do that. But China is very secretive, and part of the civilian space program is that you’ve got to be transparent.”

As of today, the Commercial LEO Development Program is scheduled to take place in two phases. Phase one, a design and development phase, will run till 2024 or 2025, while the second phase is anticipated between 2028 to 2030—fostering a smooth transition and handoff of services.

“After the space station retires and we are utilising these commercial destinations for services, the hope is that we have this robust LEO economy at that point,” Snopkowski told Inverse. “Where there are numerous people that are able to access space—they come there to work, they could play, they could live—and NASA is just one of those many customers that are participating in these destinations.” With the ISS inching closer to retirement as we speak, the leaks and cracks on its system seem to spell the beginning of a new horizon. And once private companies dominate the unknown and beyond, we can truly say that the space age has truly begun.