What dating in China is like for members of the LGBTQ+ community

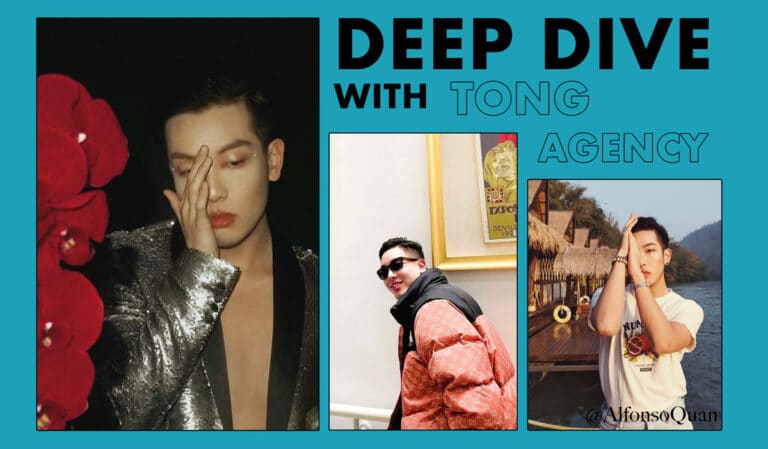

In the first Deep Dive of our three-part series Dating in China, created in partnership with cross-cultural agency TONG, we looked at dating technologies in the country and how COVID-19 impacted the way people use them. In this second Deep Dive, to shift the narrative and focus on the perspective of the LGBTQ+ community, Screen Shot spoke to Alfonso, 25, about what dating in China as a gay man is actually like and whether dating apps truly allow him to connect with a wider community.

Discussion of LGBTQ+ issues in China

Homosexuality has been legal in China for more than two decades and the Chinese Society of Psychiatry, which is the largest organisation for psychiatrists in the country, stopped classifying it as a mental disorder in 2001. But same-sex marriage is not recognised, and some LGBTQ+ people still struggle for acceptance, especially when it comes to close family members with traditional expectations.

Discussion of LGBTQ+ issues remains contentious, with activists complaining of tightened restrictions on public discussion in recent years. A 2016 report published by the United Nations Development Programme found that no more than 15 per cent of LGBTQ+ people in China had come out to their close family members.

As a result, in recent years, a number of big companies have shown their support for the LGBTQ+ community (and for the potential market the community offers). According to the BBC, in 2015, e-commerce giant Alibaba “staged a promotional event to send seven same-sex couples to the US so that they could marry.” Nike has also been known to sponsor t-shirts at the Shanghai Pride run.

But many Chinese citizens saw these pledges of support more as a consumer trap than genuine progress. “It’s not about LGBT issues. They know we have money and they want to take our money. We have no rights but our money is taken away by these companies,” said Fan Popo, a filmmaker, writer and activist from Shandong when talking to the BBC.

But that would be ignoring everything that Blued, China’s largest gay dating app, stands for.

China’s largest gay dating app

Through a quick Google search, you’ll stumble upon the dating app Blued easily, as well as all the hype that surrounds it. Described as “one of the biggest gay dating apps in the world” by The New York Times in 2020, Blued was founded by 43-year-old, ex-police officer Ma Baoli who, decades ago, had suffered from the sheer volume of online pages telling him he was a pervert, diseased and in need of treatment, simply because he was gay.

Launched in 2012, the dating app caters specifically to the gay community. In July 2020, Blued went public with an $85 million debut on Nasdaq—“a remarkable tech success story from a country that classified homosexuality as a mental illness as recently as 2001,” writes The Straits Times.

The app’s journey started in the early 2000s when Ma began writing on Danlan.org, a blog and forum about his life as a gay man, where he was known as ‘Geng Le’. At the time, there were few places in China for gay men to socialise. “Everyone was scared of being found out by others,” explained Ma.

As his blog gradually expanded into an influential online forum for LGBTQ+ people in China to share lifestyle articles, health advice and short stories, increasing media coverage of the website outed Ma to his co-workers. This prompted him to leave the police force in 2012 to focus on Blued, which was launched the same year as mentioned above.

To be more precise, in 2012, he first founded the company BlueCity (evoking memories of the coastal city Qin Huangdao where he trained and worked as a policeman). Then, in November of the same year, Ma launched Blued, his own dating app using smartphones’ GPS capability to find gay men nearby—think of it as the Chinese version of Grindr. As soon as it launched, Danlan members were quick to try it out.

Today, Blued has more than 58 million users in China and other countries including India, South Korea and Thailand, which put it beyond US-based Grindr.

Blued’s impact on China’s new generation of daters

Despite its predecessor being repeatedly shut down in the first few years of its existence, Blued has largely avoided conflict with the authorities. Its parent company, BlueCity, has managed to go for a cautious approach in raising mainstream awareness and tolerance of the LGBTQ+ community.

Among other things, BlueCity runs an online platform that sells HIV diagnostic kits and brokers consultations with doctors as a move to tackle the stigma around the virus, which has played an important part in the discrimination against gay men and prevented people from seeking medical care—something not so different from the way the rest of the world reacted to HIV in the 80s and 90s.

But the dating app still faced its fair share of problems. In 2019, it temporarily had to freeze new user registrations after local media reported that underaged boys had been using the app. From then, the company pledged to tighten age and content controls.

Overall, however, Ma’s app has helped build a brighter and healthier image of the LGBTQ+ community, in turn leading to more open-mindedness in the new generation of Chinese citizens.

Meet Alfonso, 25, Creative Project Manager living in Shanghai

Although Alfonso spent some years of his childhood in Shanghai, only to come back later on in his life, he was born in Palma de Mallorca, Spain, having also lived in London and Madrid. When meeting him, it’s clear to see how the diverse cultures he grew up surrounded by have impacted his own personality and character.

As a young gay man starting out in the fashion industry, Alfonso exudes creativity, ambition and enthusiasm—even, or should I say especially, when he agreed to speak to Screen Shot about his relationship with LGBTQ+ dating apps and online dating in general. “I’m a fashionista. I adore everything that is glamour and fashion-related,” shared Alfonso when introducing himself.

Because of his mixed cultural background, Alfonso explained that he primarily tends to go for Grindr and Tinder instead of more ‘local’ apps such as Blued. Speaking about the main differences between dating tech in China and the rest of the world, Alfonso said that “It’s mostly the same. However, when I lived in Spain and started using dating apps after I turned 18, it was such an exciting experience.”

“Well, I’m gay,” he continued, “and I had never had a gay sex experience before that. I started discovering these apps, along with my sexuality, in Spain. I finally felt like I could connect with many interesting people. But my usage of dating apps in Spain compared to China was not that different in retrospect. In both cases, it’s about connecting with like-minded people.”

“And sex!” Alfonso jokingly added.

How live streaming is taking over China

When Alfonso showed me his phone’s dedicated folder to his selection of dating apps, I listed apps such as Grindr, Tinder, ROMEO (also known as Planetromeo or Gayromeo), Scruff, Recon, and Blued. “It’s just the Chinese version of Grindr,” explained Alfonso, confirming what I had read previously.

“Grindr is my favourite,” he continued, “because it’s real-time, and you can set your perimeter to 5 or even 10 kilometres away if you want to search for people who are—or aren’t—around you. People on there are trying to find friends, relationships, or just a hookup.”

As for Blued, Alfonso shared that he is not a fan of the app. “When I came back to China, Blued was just a poor copy of Grindr. However, since then, our dating technologies have immensely developed, and Blued has turned into a live streaming platform, instead of what you would typically expect from a regular dating app.”

Indeed, Blued’s live streaming feature has gained enormous popularity recently, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic put the world into lockdown. Like many other apps trying to survive the coronavirus-induced dip in our dating lives, Blued put extensive effort into promoting digital ways of connecting and ‘meeting’ with potential partners. From its live streaming ‘broadcast’ feature to its standard video chat option, the app had to find new ways to keep its users engaged. To Alfonso’s dismay, it certainly succeeded.

“Live streaming is a huge trend here in China. All the popular people here are trying to set up channels on Blued in order to become KOLs [key opinion leaders] instead of connecting with someone else for authentic reasons. And I find that quite weird, which is why I don’t use the app that often.”

As reported by TONG, “2020 will go down in history as the year that—among other things—catalysed the development of live streaming,” adding that “well over half a billion Chinese consumers tuned in to a live stream at some point this year.”

Although the buzz surrounding live streams has not yet reached its full potential in Europe, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated its trajectory. Slowly but surely, dating apps that are popular in Europe have started introducing the feature to satisfy their users. Hily introduced its ‘one-to-many streaming and speed dating’ feature, while Tinder promoted its ‘face-to-face video chat’ option.

Meanwhile, Instagram Live notifications ruined our WFH concentration on a daily basis, and Twitch became a second home to some.

“I enjoy live streams, however, in China, once people start live streaming regularly, they end up thinking they’re celebrities. So when people actually try to connect with them on dating apps, which after all is the end goal, they simply reject them. They don’t want to talk to them because they basically feel superior,” Alfonso further explained.

As a result, Alfonso feels like Blued has almost turned into a marketplace app where people use the platform’s popularity in order to sell users something completely different from what they came for in the first place. Looking back to what Chloe previously explained about dating apps in China being used as marketing tools for many, Alfonso’s point resonates.

Fashion bragging as a dating app no-no

When speaking about his dos and don’ts when it comes to building the perfect dating profile, such as tips like “always use a picture of yourself with warm tones” or “smile—show some teeth,” Alfonso was also quick to point out his most no-go ‘profile occurrence’, which he had to learn the hard way. “Do not wear anything that is too fashionable or stylish in your profile pictures.”

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

“I have had some bad experiences with it. Once, I decided to change all my profile pictures to an editorial I worked on. Shortly after, I realised that no one wanted to start a conversation with me. I actually found out that there is a Chinese saying that goes along the lines of ‘the closer you get to fashion, the further love will go’, meaning that you’ll have a hard time finding real love if you’re too fashionable.”

While generalities should not be made, Alfonso further explained that most users on dating apps in the country act—and therefore dress—quite straight. Opting for something more flamboyant to highlight your personality on your profile could potentially translate into the wrong message. “All the accessories, the makeup, and out-there clothes will scare other people away and stop them from connecting with you,” said Alfonso.

Despite of the country’s emerging fashion scene as well as the crucial part it plays in the global fashion market, Alfonso’s argument clearly highlights the progress that is left in terms of what is acceptable to wear or not—something that can come as a surprise to those interested in Chinese fashion designers such as Samuel Guì Yang, Yushan Li, Jun Zhou or Xuzhi Chen.

Shanghai’s digital and real-life LGBTQ+ community

“Shanghai is very international, right? So the city’s LGBTQ+ community is very diverse—we have people from all over the world. But I have found myself that members of the community tend to only hang out with certain groups of people. They do not particularly want to welcome new members at first, or at least until they really get to know them,” explained Alfonso.

With almost 28 million citizens, Shanghai is not only China’s largest and most populated city, but it is also the most densely populated city in the world. Taking this into consideration, it can seem surprising that its LGBTQ+ community is not as welcoming as one might expect.

However, in terms of open-mindedness and mentality, Alfonso agrees that Shanghai distinguishes itself from the rest of the country, because of its foreign population. “This foreign influence on the city means that people can relate to each other more easily. What I should note though is that approximately 80 per cent of gay foreigners who move to Shanghai are what we call ‘rice queens’—Westerners who are particularly into East-Asians.”

“The reverse version of rice queens,” explained Alfonso, “would be ‘potato queens’.” Because Westerners eat potatoes, and Asians eat rice, get it?

Although Alfonso admitted to using dating apps mostly to meet sexual partners, he explained that on Grindr, users are free to customise settings depending on what they’re looking for. “Some people are only looking to chat, others are here for relationships, and some for hookups. So for some people, dating apps are a way to find new friends too, which for me seems near impossible, because when you want to meet a friend here in Shanghai, you’ll have to get drinks, have dinner—it’s all very time consuming, you know?”

While this approach to starting a friendship seems pretty standard, Alfonso further explained that in the largest city in the world, efficiency is key. However, he also added that dating apps are an essential part of his life, one he knows he can also use to help further his career path.

When online dating leads to online relationships

Alfonso met his first love, Shane, on Grindr during his sophomore year. They eventually separated when he was about to graduate in 2019 as Shane had to go back to Canada. After the tough breakup, Alfonso shared that his relationship with dating apps changed into something else, “a channel for desire release,” he told Screen Shot when first introducing himself.

Fast forward to 2020, and the COVID-19 pandemic led to imposed lockdowns all over China. As a result, Alfonso explained how “less fresh meat came to Shanghai.” “Obviously, we got bored of what we could get within a 10 kilometres perimeter, so in order to kill time, I reinstalled Tinder and started swiping right again to match the hotties on there,” he added.

Thanks to Tinder’s paid Passport feature, Alfonso had access to people from all over the world, and the app’s algorithm made sure to show him its best ‘finds’ according to his taste and preferences. And it worked! A few weeks before speaking to us, Alfonso matched on Tinder with his current boyfriend, a Spanish man called Jon working in movie production and living in Canada—yes, like Shane.

“We got on so well, and I didn’t expect to have this déjà-vu feeling bringing me back to a time before the pandemic. I especially did not expect that I would end up in a virtual relationship.”

For many, the terms ‘online relationship’ or ‘virtual dating’ pop up in our heads along with the plot of the movie Her, which tells the story of introvert Theodore who falls in love with his virtual assistant, Samantha. Powered by advanced AI technology, Samantha is able to cleverly and considerately respond to Theodore’s emotional needs in ways no one else in his life had ever done before.

While Alfonso is dating someone very real, unlike Samantha, and Her is, of course, a work of science fiction, it looks like, in recent years, our own understanding (and acceptance) of the many romantic possibilities dating technology can offer users has evolved.

In China, this acceptance of online relationships and virtual partners—which are two different things—has come from the rise of an entire industry back in 2014. As virtual boyfriends and girlfriends emerged in the country, paying customers received emotional support, care, and the feeling of being loved over the internet.

“Known as ‘virtual lovers’, these individuals sell warmth and happiness to clients through platforms like e-commerce marketplace Taobao and internet forum Baidu Tieba, often via a virtual storefront run by an experienced retailer,” writes Sixth Tone. “Crucially, in this kind of care-for-money transaction, no one ever meets the other in person. Depending on the virtual lover’s comfort level, he or she communicates with customers via text, voice message, or video call,” the article continues.

Of course, when it comes to Alfonso’s online relationship, some slight differences are to be noted. Both he and Jon met on Tinder as he mentioned, and Alfonso didn’t intend to keep this relationship digital-based. In fact, he told Screen Shot that he fully intends on meeting Jon as soon as possible.

“For me, using Tinder almost feels like I’m the boss and I’m interviewing potential ‘contestants’. All you have to do is swipe right or left, and I actually accidentally swiped right on Jon. I didn’t expect much from Tinder. I was just bored and wanted to see how people interact on there.”

After swiping right on Jon, Alfonso started chatting regularly with him, and almost instantly, they connected. “The fact that he is Spanish helped us connect on a deeper level. He lives in Canada, and although I don’t particularly like that place because of my previous history with Shane, I find this coincidence interesting. We went on to share personal contact details, and quickly started FaceTiming almost every day.”

Although Alfonso has never met Jon face to face, he believes in their relationship’s potential and is thankful for the COVID-safe opportunity that dating technologies have offered him.

Our open conversation with Alfonso has allowed us to gain insight into China’s LGBTQ+ dating scene and how technology has impacted it in both positive and sometimes negative ways. As apps like Blued and Grindr open up new opportunities for the country’s LGBTQ+ community, they simultaneously help promote messages of acceptance, non-judgement, and freedom.

But just like the rest of the world, China still has a long way to go. “If I wanted to get married, I would do it in Spain, simply because it’s legal there,” shared Alfonso after explaining that his parents were not aware of his sexuality. The question that remains is whether dating technologies will be the last push China needs in order to allow same-sex marriage. For now, same-sex couples in China are only allowed a ‘guardianship appointment’.