Looking is the web app that sheds light on toxic dating culture within the queer community

Let’s face it. Dating in the ‘apps’ era can be downright demoralising. With virtually infinite choice of prospective lovers comes an equal volume of heartbreak, ghosting, self-doubt, and rejection.

While the trials and tribulations of online dating aren’t exclusive to the queer community, the symptoms of depression, loneliness, and anxiety associated with the apps seem to be particularly potent among gay men using Grindr, Scruff, and similar hook-up apps. Transmedia artist Nicholas Pfosi set out to explore this phenomenon through a media project called Looking, in which interviews and photographs of gay men are presented on a web app mimicking Grindr.

Like many queer men, Pfosi found himself encountering a recurring theme of men describing going on hook up binges, usually with strangers, that leave them feeling unsatisfied, depressed, and frustrated. And after conducting some research into the matter, Pfosi decided to try and put these themes and observations into words and give them some sort of expression.

What began as an experiment in Boston with several interviews had quickly morphed into an outpouring of dozens and dozens of men recounting their, mostly negative, experiences with Grindr and the sense of distress it leaves them with.

“I’ve just been talking organically with these individuals,” Pfosi told Screen Shot, “and I’m thinking to myself ‘people need to hear this and understand what you’re saying; people need to see themselves in your story’.”

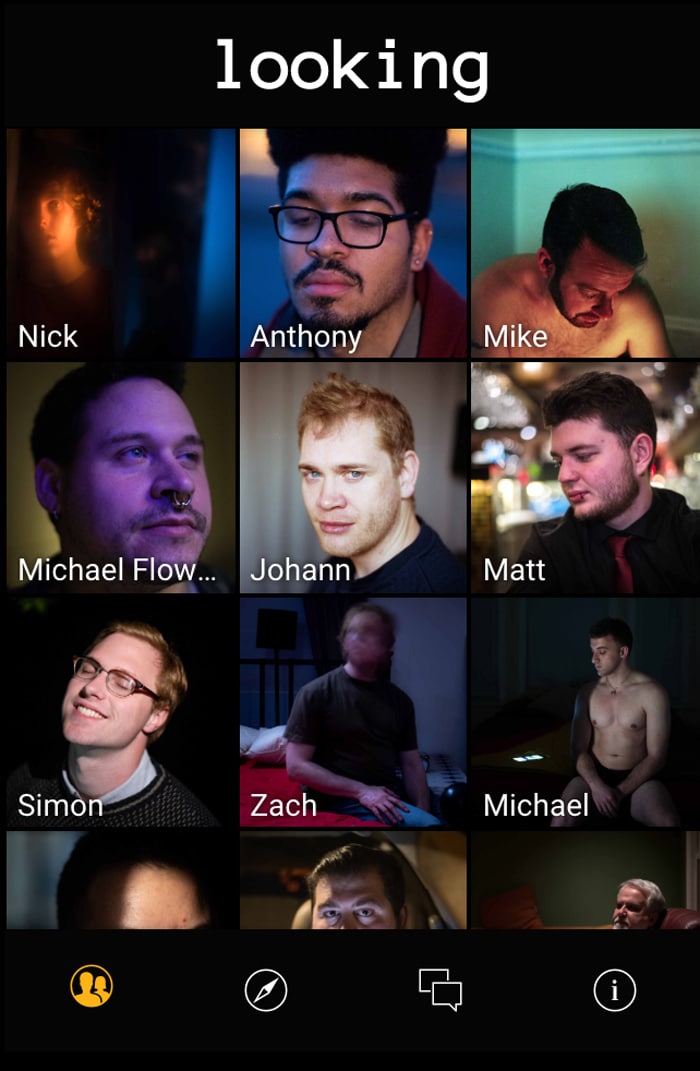

The Looking app, which was created in collaboration with web-developer Mike Fitzpatrick, features the familiar Grindr grid, only instead of a potential hook-up, each picture leads the viewer to the individual’s account of their experience with the app. The interviews, presented in a Grindr chat format, provide raw testimonies of men grappling with challenges such as depression, loneliness, body image issues, and HIV, all within the context of hook up apps.

“There’s a lot of dysphoria and distress around gay people’s relationship to romance and sex because we’re kind of indoctrinated or socialised with a certain modality about being sexual or being romantic in the world,” said Pfosi. “And I think one of the best ways to subvert norms is through narratives and stories; people really start to think differently when they hear an account, or they hear a story of someone feeling the same way, struggling with the same things.”

Pfosi points out that the very design of the Grindr app plays a crucial role in creating the problems associated with it. On Tinder, for instance, people have to match with one another and indicate that there is mutual interest (at least on some level) for a conversation to start. “With Grindr there’s no process like that,” said Pfosi, “it’s all about geographical proximity… you can message anybody, regardless of who they are or if they’d be interested in you just because they’re near you. The design of the app informs the function that it has. So that’s why it’s important for me to imitate that experience.”

“There’s a whole psychological component to it,” Pfosi added. “There’s kind of a dopamine rush when you get a lot of messages or people tap you or when you change your picture and suddenly new people message you. And even without looking for sex you’re like ‘oh yeah, this feels kinda good’. And I’ve done this too, opening the app just to see what’s going on.”

Pfosi, however, is cautious in his critique of the app itself, arguing that it’s merely a symptom of a larger problem. “If it weren’t [Grindr] it would just be something else,” said Pfosi, “because, at the end of the day, it’s a manifestation of how gay male dating culture has grown, and what it has grown into. It’s about sexual gratification.”

What, then, could be at the base of this toxic dating culture?

In his widely acclaimed book The Velvet Rage, Dr Alan Downs ascribes the ongoing psychological struggles of queer men (particularly, but not exclusively, when it comes to dating) to deep-rooted shame we carry from growing up queer in a straight world. In many cases, Downs claims, this shame goes untreated and unacknowledged, and so we grow into adulthood with an internalised sense of unworthiness that makes us both primed to expect rejection and highly discriminatory of other people who we sense share the same symptoms. This explains why when we come into contact with one another we often treat each other viciously, and why predominantly gay spaces—be it neighbourhoods, clubs, bars, or dating apps—are prone to become breeding grounds for further hurt, isolation, and trauma. We often don’t function as a real community, but rather as a cluster of deeply traumatised individuals who mirror each other’s internalised shame.

According to Michael Hobbs, a Seattle-based writer who greatly influenced Pfosi’s work, this is nothing short of an epidemic. A research by the Community-Based Research Centre (CBRC) indicates that as queer men we’re between 2 and 10 times more likely to commit suicide than our straight counterparts, and are twice as likely to suffer from major depression. We are also prone to higher rates of diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, allergies, asthma, and more. Researchers correlate these phenomena with what they call ‘minority stress’ syndrome as well as trauma experienced in gay relationships and environments after coming out.

In order to truly tackle this toxic plague of depression, anxiety, and loneliness among queer men (and arguably in the queer community in general), we must engage in the challenging but necessary work of self-exploration and healing, while, simultaneously, building a real community. Not necessarily one that is fabulous and chic and blunt, but rather a network of communities that foster genuine human connection and support.

Pfosi’s goal is to have people upload their own stories to his Looking web-app, a function that is still in the works. “What I would really love for this app is for it to, through this submittable profile capability, become a way to interface with this work commenting on the LGBT dating experience, specifically the gay male dating experience, in a deeper, more conversant way,” said Pfosi. “There’s this feminist term,” he added, “called consciousness raising—bringing together ideas and experiences between a politically or socially marginalised group, and what facilitates that is narrative and empathy, and I want this project to be one of those tools that facilitate this kind of conversation.”

Ultimately, a sense of belonging must transcend the screen and be formed through real life connections and support networks. It is initiatives such as Pfosi’s, however, that set us in the right direction and have great potential to inspire empathy, decrease alienation, and spark some much needed conversations.