Scientists have now discovered microplastics inside newborn babies

For decades, scientists have been warning humanity about the deadly consequences of microplastics: small fragments of plastic that can either be microscopic or resemble a grain of rice. Last year, several studies proved how these tiny particles are dispersed around the globe in the atmosphere—triggered by wind and rain. Then came the revelations that we could actually be eating up to five grams of microplastics, the approximate equivalent of a credit card, every single week.

As of today, microplastics have invaded our kitchen, guts and beauty regimes. In a shocking twist of events, however, researchers have now confirmed the presence of the material inside the human placenta and newborn babies.

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Health Perspectives (EHP), detailed the connection of both nanoplastics (tiny particles that are manufactured unintentionally) and microplastics with pregnancy and children’s health. Reviewing 37 different articles, the researchers noted how it’s practically impossible to prevent children and infants from ingesting and absorbing microplastics, even before they’re born.

In these terms, the researchers explained how we’re exposed to toxic chemicals in the environment especially as foetuses in a female womb and throughout our childhood. “Children do not have a fully developed immune system and are in a very important phase of their brain development. This makes them particularly vulnerable,” Kam Sripada, a neuroscientist from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and lead author of the study, said in a press release.

What’s further shocking is that children are more likely to be exposed to microplastics than adults. “No one knows exactly how much microplastic a child ingests. But several studies now suggest that today’s children absorb microplastics in their bodies as early as at foetal age,” Sripada added. “This is concerning.”

The lack of studies for the demographic’s exposure to microplastics is partly due to the limitations of technology for researching very small particles in the atmosphere. “Although a lot of research is being done on microplastics, studies on the health effects of these plastic particles are limited,” Martin Wagner, an associate professor of biology at NTNU, said in this regard. “This applies especially to the effects on children.”

For example, more insights are required to acknowledge children’s exposure levels to the tiny plastic fragments at school, in neonatal wards and through breast milk, breast milk substitutes and baby care products.

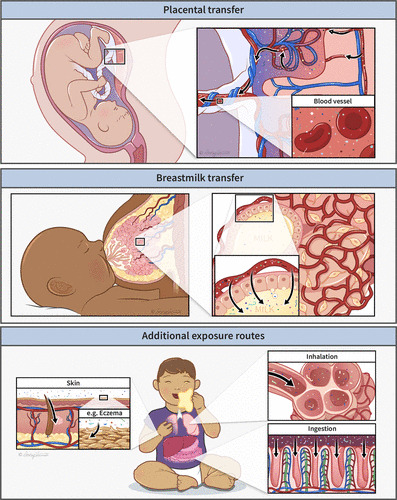

The list doesn’t end there either. According to the researchers, the demographic in question can ingest microplastics in several ways—including infant formula, baby bottles, toys, textiles and food packaging. They can also absorb the toxins via the placenta as a foetus from the mother. Household dust, however, is one of the major factors in play here. “When microplastic particles end up in household dust, children may come into contact with them through crawling and playing on the floor. Then they put their fingers in their mouths,” the press release noted. The team of scientists, thereby highlighted how it’s “almost impossible to prevent children from ingesting plastic.”

But not all hope is lost. There are certain ways in which parents can reduce the amount of plastic that their children are exposed to. Some of the pointers suggested by the team include cleaning the house regularly with soap and water, preferring personal hygiene products with less plastic and making sure that their food comes into as little contact with plastic utensils and cutlery as possible. Choosing the right building materials that don’t contain PVC is also on the list.

In the end, be aware that microplastics don’t just contain plastic, but carry a variety of toxic chemicals as well. “Nano and microplastics are so miniscule that they can travel deep into the lungs and can also cross into the placenta. At the same time, they transport dangerous chemicals with them on their journey. That’s why we believe that they can be a health risk for children,” Sripada concluded.

Given how plastics can take hundreds of years to biodegrade, each fragment of microplastic simply breaks down into smaller pieces—thereby circulating indefinitely in our atmosphere. Until we get more insights into these deadly particles, I guess we’ll be ingesting credit cards-worth of plastics every other week.