Photographer Gosha Bergal on perpetuating the Soviet school of photography while challenging Russia’s pedagogical system

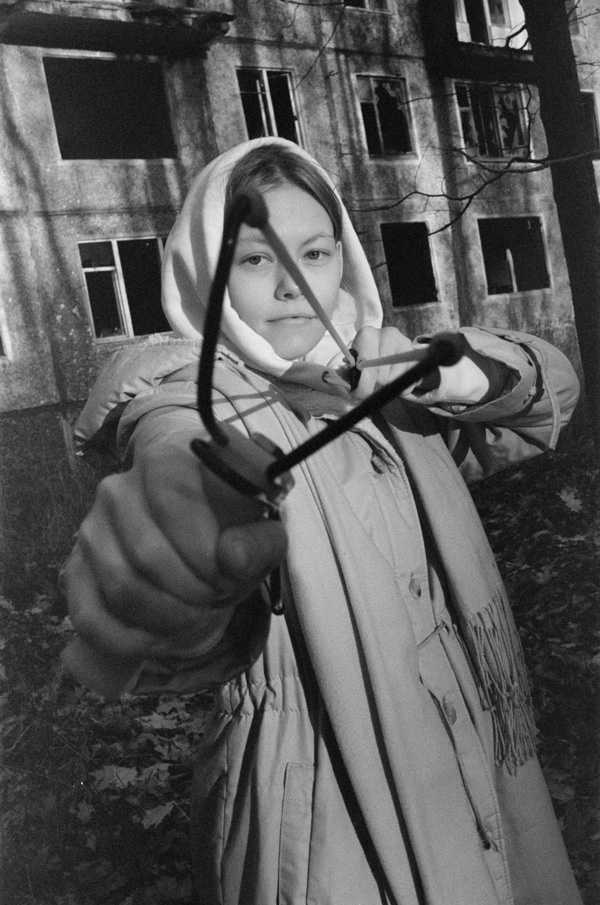

“I’m known for taking pictures very close, and the older I get, the closer I get,” Bruce Gilden, one of the most iconic street photographers of our time, once said. The same quote comes to mind when looking at some of Russian photographer Gosha Bergal’s raw-yet-highly-technical work. From capturing Moscow’s youth-led protests since 2011 to perfecting the art of shooting everything that surrounds him and everything that he considers important, here’s what advice Bergal had to share with Screen Shot Pro.

From skateboarding to photography

For someone with close to no idea as to how certain photographers manage to capture certain moments with such strong emotion, I had a good feeling that Bergal had somehow been influenced by the skateboarding community prior to his photography career. Not to compare his work to the likes of skate photographer Atiba Jefferson for example, as that would downplay the former’s wide range of subject matters, but Bergal’s work seemed too honest and revealing for me not to link it to the skateboarding community’s similar free-thinking approach to creativity. And, as he told me himself, I wasn’t too far off from the truth.

When asked when he first started experimenting with photography and what led him to it, Bergal explained, “I was skateboarding with friends, and of course all of it had to be filmed. That’s the first time I consciously held a camera in my hands.” However, he ended up getting injured and had to stop skating. “I always thought that I would stay in the skateboarding industry as a photographer, but photography simply had other plans for me,” shared Bergal.

Bergal decided to go to university in Moscow instead, where “I began to study photography techniques and technology. I also went to Berlin under a student exchange programme, and took a photography course at the Berlin photography school Focon.”

After four years of studying, when Bergal graduated, he had already begun to switch from digital photography to film photography. “I learned how to develop and print photos myself. That was back in 2011.” Speaking to the photographer, it’s clear to see how much respect he holds for his education, or pedagogy in general, which I’ll get back to shortly. That being said, I couldn’t help but wonder whether he would promote autodidacticism photography over it.

Theoretical knowledge first

“I believe that receiving a certain type of education when it comes to photography is essential, both for professionals and artists,” Bergal told me. “Photography is all about optics, mechanics, chemistry, physics, and art. Therefore, it would be very difficult for a young photographer to craft their skills without theoretical knowledge.” You know how it goes, “learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

First and foremost, photography is a technical skill. In order to truly appreciate how light and shadow can turn a simple picture into a photograph of interest, a basic understanding of the mechanics of photography is required. The very fact that anyone with a camera can take pictures means professional photographers need to be exceptional in one way or another. Otherwise, why would your work stand out from the rest, right?

“But, it is not at all necessary to go to study photography at university,” adds Bergal. “Besides, institutions often follow the path of wider conjuncture, which is the complete opposite of art. I read books on photography by old Soviet masters, and I also draw inspiration from there.”

Of course, the photographer also has his teachers and mentors to thank too, “A.V. Agafonov, N.M. Udalova, Y.M. Ydilevich, V.N.Kornyushin, and Mukhin I.V. They are all heirs of the Soviet school of photography, and I would like to think I’m here to continue this glorious tradition.”

But if you’re not sure whether paying a substantial amount of money just to go to university, Bergal has the answer you’ve been looking for, “Most of the information that schools or universities are trying to sell us in the form of photography courses, master classes, and modern books is nothing. Don’t waste your time and money, it’s available on the internet for free! Masters rarely share their real experience, and you can find the operating instructions for a particular device yourself. Probably the best advice is to take pictures. Shoot and don’t stop, don’t waste time on dubious connections or profits. It is important for your creativity to be completely disinterested, for the sake of your creative process.”

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

An eternal search based on the study of space and its behaviour

When asked to describe his take on photography and what influenced his style, Bergal compared the former to “an eternal search based on the study of space and its behaviour.” The photographer’s subject of choice is people as well as the way they live, move, breath, behave, and so much more. “Photography is not just creativity, it is my teacher of life […] I study visual means and artistic techniques in order to establish contact with space, with its metaphysical manifestations,” he once told the Paris-based photography edition PARAD.

Bergal’s favourite photographer is Maxim Petrovich Dmitriev, a Russian photographer of the 19th and 20th century, and one of the pioneers behind documentary photography. “He left a cosy studio to go and film the hunger in Nizhny Novgorod [a large city on the Volga River in Western Russia].” In a way, one could say that Bergal’s work draws some inspiration from Dmitriev.

As I mentioned before, Bergal has been documenting anti-Putin demonstrations in Moscow for a little over ten years now. “Over the years, the opposition in Russia has been literally killed,” he told i-D in January 2021, after he shot a series of images on Pushkin Square for the publication. “People are almost accustomed to the fact that it is impossible to change something in this country; many do not vote in elections. But thanks in part to Alexei Navalny, other opposition bloggers, and the internet, a new wave of socially active citizens has emerged among young people,” he continued.

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

In perspective, leaving your “cosy studio to go and film the hunger in Nizhny Novgorod” and regularly putting yourself in the middle of anti-Putin protests for ten years both sound bold to me. But then again, what’s photography if not a constant search for something, be that the exploration of the mundane or even the violence in life?

“Most often than not, photography is of an applied nature, but one should not forget about its social side either. Today, documentary photography is dead, because any eyewitness with a smartphone suddenly becomes a ‘documentary filmmaker’ and it’s easier and faster for editors to buy unprofessional materials,” explained Bergal on the topic of candid (or candid looking) photography.

“But it also has its positives,” he added. “It makes young photographers look harder for an interesting topic, work with drama and other expressive means of photography. In my opinion, today’s documentary photography has moved into the category of art.”

When asked about his number one tip for working with people behind the scenes, the photographer explained that his process is as simple (meaning difficult) as it gets, “You can seize the moment, or you can try to recreate the situation. But my trick is as simple as possible: ‘Hello, my name is Gosha, I’m a photographer. You look very interesting! Let me take a picture of you?’ This does not always work, I often end up with a refusal, sometimes it is even dangerous, but I am not cheating on myself.”

He further shared that there are times when he knows he can’t ask, “you just need to shoot right now. Photography teaches not only composition, it is also psychology, and most importantly, it teaches you to look three steps forward, assess the situation from all sides, so you need to shoot more.”

Can your social media presence truly land you some jobs?

When it comes to photography, having an engaged (and engaging) social media presence can be tricky, to say the least. Instagram photographers are a thing, and many actual professional photographers think they don’t deserve that title. But what if you’ve gained theoretical knowledge first and are now looking to expand your reach?

“I love the internet, it allows you to think much wider than the boundaries that are built by society and the state. It was social networks that helped the clients I’ve worked for find my work in the first place. It was unexpected and pleasant—the first publication that commissioned me was Neon, a magazine based in Hamburg, Germany,” shared Bergal.

“Daily posts on your social pages will provide you with an influx of subscribers, so think about a content plan for the week ahead, and adhere to this strategy,” he continued. “Imagine that your page is someone’s favourite series—do not upset your viewers, publish new works! Of course, it is difficult and it is not always possible to keep such a rhythm, but it will help you find your audience.”

In the end, it all comes down to the same point Bergal made previously: as long as you’re willing to put in the work and master the technical aspects of the art, then why shouldn’t you take advantage of the exposure social media platforms have to offer?

Gosha Bergal’s go-to cameras

“At the moment, I am shooting with a Leica M5, and I’m very happy with it.” Debuted in 1971, the Leica M5 is an interchangeable lens 35mm film rangefinder camera. Although reviews tend to be mixed, depending on the shooter using it, the Leica M5 can be either “singularly elegant or uniquely cumbersome,” reads the first review that showed up through my Google search. Another one simply reads: “it’s the camera that nearly put an end to the Leica rangefinder after it was balked for being too big, heavy, ugly and incompatible with what came before. Despite this, the Leica M5 seems to have been given a second chance.”

“For beginners, I would recommend Japanese or German SLR cameras, which have good optics and a reliable mechanism—everything a photographer needs,” adds Bergal. “And for all aspiring creators, I recommend that you learn the basics of exposure and composition before picking up your camera.”

Gosha Bergal’s big no-nos

Speaking about the artists he looks up to for inspiration as well as the artistic movements he dislikes, Bergal admitted, “I do not like institutional art, it is too loaded with theory. The ordinary viewer does not understand it, and artists in pursuit of conjuncture are losing themselves.”

As for inspiration, “I turn to myself—I remember my childhood, the films I watched, the books we read with my grandmother. Actually, my grandmother did the reading while I looked at the pictures! Maybe that’s why some people call my work ‘honest’. And if I go to shoot something extraneous, then I put myself in the hands of curiosity, trying not to forget to correctly set up the camera and build the composition.”

Because he mainly shoots on film, Bergal hardly edits his pictures. “I run everything through Adobe Lightroom, and, if necessary, make preparations before printing in Photoshop,” he told Screen Shot Pro.

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

So, what’s next for the photographer?

“Good question! I see myself in a circle of creative, talented people, who are working on large commercial projects, which allow us to engage in independent creativity. And of course, I am engaged in pedagogy. Both now and in the future. I think that it is necessary to change the pedagogical system in Russia, it is simply outdated.”