Isolation, fear and foreboding: how the original ‘Metroid’ turned out scarier than actual horror games

Horror games are plentiful in the gaming world, from Resident Evil to Silent Hill, it’s a fan favourite genre to be sure. But it’s only in the last few years that we’ve seen horror games back on form, with the release of Resident Evil 7 in 2017 really sparking the ‘return to terror’. Previous titles such as Resident Evil 6 and Silent Hill: Homecoming swapped a lot of the spooks for action, leaving many players underwhelmed and feeling like the genre was losing its way.

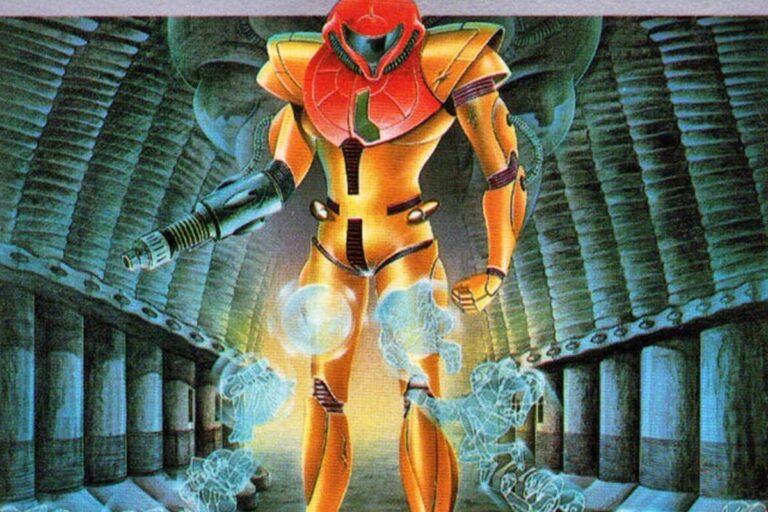

But what if I told you that there is one series out there that has consistently kept up the scares over the 36 years since it first graced our screens? Oh yeah, and it’s not even a horror game. I’m talking about Metroid, Nintendo’s answer to Alien and possibly the scariest non-horror game franchise out there. What the heck is he going on about, you ask? To understand that, you have to understand Metroid’s history first. Let’s take a look.

History of ‘Metroid’

Metroid was originally released in Japan on the Famicom—Japan’s version of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)—in 1986. Set on the planet Zebes, the story follows Samus Aran as she attempts to retrieve the parasitic Metroid organisms that were stolen by Space Pirates and their leader Mother Brain, who plans to replicate the Metroids by exposing them to beta rays and then use them as biological weapons to destroy Aran and all who oppose them.

From there, a story of galactic proportions was set into motion, with the sequel, Metroid II: Return of Samus releasing for the Gameboy in 1992, where Aran is tasked with travelling to the Metroid home world of SR388 to destroy them all, as they pose too great of a threat to the galaxy. While escaping the planet however, the hero witnesses the hatching of a baby Metroid, who imprints on her, believing Aran to be its mother. She then escapes with the baby and hands it over to the Galactic Federation for safe keeping.

In 1994, Super Metroid for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) was released and continued not long after the events of Metroid II. The research station where the baby Metroid was left is attacked by the Space Pirates and their leader, a giant pterodactyl-like monster known as Ridley, and the baby is stolen. Aran, who responded to the station’s distress signal, follows the Pirates back to their home world of Zebes and once again braves the depths of the planet to retrieve the baby Metroid.

At the stories’ culmination, Aran—who had been gravely injured by a rebuilt and more powerful Mother Brain—is saved by the baby Metroid, which sacrifices itself in order to bestow the Hyper Beam on the game’s hero, a powerful weapon that is strong enough to destroy Mother Brain once and for all. In a nail-biting escape sequence, Aran escapes the planet as it self-destructs.

It wasn’t until 2002 that we were able to witness the next instalment of Aran’s legacy. Metroid Fusion for the Gameboy Advance (GBA) was released and followed our main character, sometime after the events of Super Metroid. After being infected by an unknown organism on SR388, referred to as the X Parasites, Aran almost dies, but is saved by a vaccine made from the cells of the baby Metroid. As it turns out, the Metroids are the natural Predators of the X. She also gains the ability to absorb X Parasites, much like the Metroids.

Her infected suit parts are sent to the Biological Space Labs (BSL) for testing, but an unexplained explosion rocks the station and Aran is sent to investigate. The X are able to perfectly mimic any natural organism they infect, and due to her infected suit containing organic components, the X creates a powerful clone of Aran with all her strongest abilities known as the SA-X.

Throughout her adventure, Aran is stalked by the SA-X and it is discovered that BSL has been secretly cultivating Metroids. Our hero, not able to allow the Metroids to live, sets the station on a collision course with the nearby Metroid homeworld of SR388 and both are vaporised in the explosion, while she escapes in the nick of time.

19 years later, the fifth and final instalment of Aran’ story came out: Metroid Dread. Following the events of Metroid Fusion, the Galactic Federation receives a video showing surviving X Parasites on the planet ZDR. They send seven Extraplanetary Multitform Mobile Identifiers (EMMI) to investigate but shortly after lose contact. Aran is sent to investigate and discovers that some of the Chozo, an ancient, highly intelligent race are still alive, and that one of them, Raven Beak, wishes to resurrect the Metroids using the Metroid DNA implanted in her at the beginning of Metroid Fusion. Finally confronting Raven Beak aboard the floating fortress of Itorash, Aran’s Metroid DNA fully awakens and after defeating the villain, who becomes infected by an X Parasite, drains the life from him.

As Itorash crashes into ZDR and the planet begins to self-destruct, Aran finds herself unable to return to her ship due to her new abilities. Quiet Robe, a Chozo who is able to wield the X and aided Aran during her adventure appears and allows himself to be absorbed, quelling her Metroid abilities and allowing her to escape, thus bringing an end to her legacy.

What tricks does ‘Metroid’ employ to make it feel like a horror game?

With all the sci-fi elements present in Metroid, it’s not hard to see how it can easily utilise horror elements to its advantage. Let’s break these elements down, shall we?

Style

For a game from 1989, Metroid is absolutely dripping with style, from its fascinating environments to its detailed character designs. But it’s how it uses these elements to induce fear and a sense of isolation that is really incredible. From start to finish, the game employs a completely black background. As soon as you boot it up, the title screen is just black with only a little environment visible. Once you begin to explore, the only pops of colour you see are Aran, who is a vibrant orange, and the different terrain and enemies you encounter—but throughout your travels you will be actively destroying bits of the environment while looking for hidden items or passageways, only adding to ever encroaching blackness.

This use of colour is also the only way you can really know what part of the world you’re in, as there is no map system, really driving home that you are lost and on your own in the depths of an alien planet.

This use of, or rather lack of colour, brings about a sense of isolation and oppression. It follows you everywhere—there’s no escape from it. Additionally, all the shades used are of a darker hue, meaning when you enter an area like an item room which uses a bright grey/white colour scheme, it almost stands out like a beacon of hope. A little respite from the darkness of the rest of the game. It explains why the final area of the game, Tourian, has a similar colour scheme to the item rooms. You’re so close to the end of the game, to escaping, it’s like the light at the end of the tunnel.

Sound

Sound plays a huge part in any video game, and it’s one of the key components of creating true immersion. Metroid does this incredibly well, especially for an NES game from 1989. Its limited, 8-bit soundtrack, while simple, really adds to the creepy and foreboding atmosphere the game creates.

The title screen starts off with a rather unsettling mono bassline, which immediately lets you know that the adventure to come isn’t going to be a walk in the park. This leads into a much more upbeat theme as you start your adventure and make your first descent into the plant. It bravely sends you off on your quest and fills you with a sense of hope. Very quickly though, this optimism is replaced with an awkward, uneasy creepiness. The music in Norfair in particular, moves in such weird and unpredictable patterns that the pauses sound almost deafening and it does a very good job of putting you on edge.

Enemy sound effects have a sullen and dull moodiness to them, which directly opposes Aran’s crisp and bouncy sounds, cementing the fact that she is the hero and that she is agile and strong. One piece of music you will encounter frequently throughout the game is the item room theme, which is particularly unsettling due to its rising and falling, bumpy bassline and high-pitched melody that plays on top. For a room that, on the one hand, gives you some respite with its colour scheme, it pulls away from that with its uneasy music, letting you know that while you may be safe for now, there’s still much worse to come.

Substance

Metroid comes from an era when video games were still very hard to complete, and lives were employed as a way to keep players going as an incentive. But Metroid in particular broke the mould, and did away with lives. If you died, you died. You needed to use a password to return to vaguely where you were before. This feature, which now would seem archaic with our quick saves and auto-saves, added tremendously to the tension felt by players. One mistimed jump or missed shot from your arm cannon and it was game over, literally. You don’t even start the game at full health, and there are plenty of rooms with enemies whizzing about that could get you killed instantly, so picking your battles and the route you take was something you really had to think about.

Metroid does a really good job of providing a good selection of enemies and long, obstacle-filled corridors for you to navigate, but as mentioned earlier, don’t expect any help. Without the use of the internet to aid you, you had to rely on memory—or if you were lucky, a paper map provided in an issue of Nintendo Power, Nintendo’s gaming magazine, but those who had one of those were few and far between. You really were left on your own in a dark, alien world, and it was all up to you whether you succeeded or failed in your quest. Your only respite was the design loops and backtracks built into the game to make exploration easier. Other than that, there was nothing else that could help you.

Well, there you have it. A game all the way from 1989 where characters were only a few pixels high, 8-bit music was considered the pinnacle of gaming and one that wasn’t even created as a horror game can still leave you feeling unsettled and on edge. While there are those out there who much prefer a good gory horror game, or a spooky, spine-chilling film for that matter, the way Metroid uses colour, sound and design to create isolation, fear and foreboding is undeniable. So the next time you go to pick up the latest horror game, just think to yourself: is it scarier than Metroid?