Climate scientist warns cyclones could soon be the norm in Europe

It’s clear the days of relatively rare extreme weather events in Europe are over. Globally, the climate crisis is at the forefront of all of our minds: from forest fires in Greece and Turkey to landslides in Japan and flash floods in major cities like New York and London. As the anxiety builds, many have taken to the streets to start demanding that global leaders make drastic changes to save our planet. Nadia Bloemendaal—a meteorologist at the Institute for Environmental Studies, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam—on the other hand, prefers to do her activism behind a computer screen, where she believes using her skills can really make a difference.

The importance of mapping extreme weather and early warning systems

Bloemendaal’s work consists of modelling extreme weather, revealing trends in the region that could have significant repercussions for life in Europe within the next half a century. She combines meteorology, mathematics and physics to produce real-world depictions of how the weather is changing across the globe. Her work, along with countless other meteorologists, is producing scientific evidence which in turn shapes the course of climate policy worldwide.

Bloemendaal originally developed her cyclone early-warning system to protect communities in the Global South, however, recently there has been a more sinister forecast for regions further North. The alarm bells are ringing closer to home. Recent instances of extreme weather, such as deadly flash floods across the continent, shouldn’t be brushed off as a rare incident. In fact, it could be foreshadowing a more dangerous, extreme and unpredictable future European climate.

The floods which hit Northern Europe in July 2021 were a tragic disaster, killing at least 180 people. However, if there is one silver lining to the incident, it was that storm warning protection systems did manage to avoid further casualties for people living in the Netherlands. It showed us that warning systems for extreme weather aren’t just recommended in Europe—they’re needed. The day where Europe is largely immune to extreme weather conditions is behind us, political leaders need to step up and implement “early warning systems and adequate communication that can save lives,” Bloemendaal told Euronews.

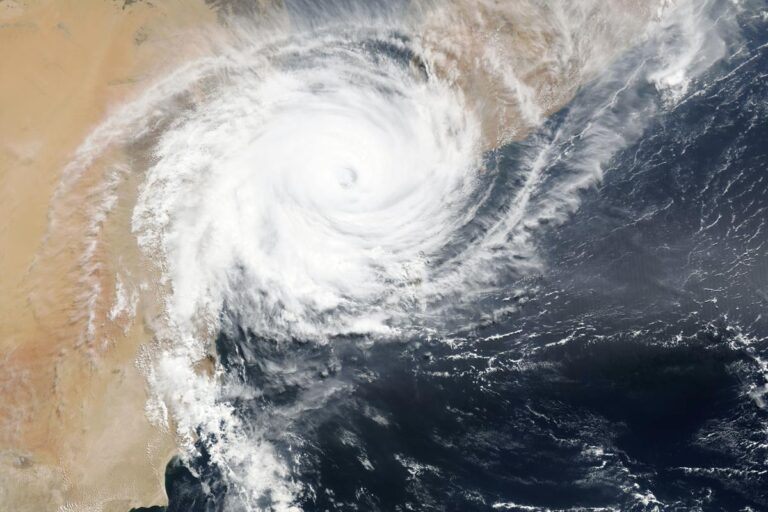

Bloemendaal indicates that a warmer climate could act as fuel for tropical cyclones, especially if seawater reaches a temperature of 30 degrees Celsius (86 Fahrenheit). In her interview, she continues to warn that seawater temperature at this level can cause tropical cyclones to “keep going and keep intensifying.”

Cyclones could be the norm in Europe

And the forecast is grim. As sea levels rise across the world, it will have a knock-on impact by raising water temperatures. This is particularly the case in the South, where rising water levels could cause northern coastal regions to reach temperatures of up to 27 degrees Celsius. Based on the science Bloemendaal is seeing, parts of the world that don’t see tropical cyclones now may see them in the next 30 to 50 years.

A recent report by the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reaffirms her fears. In the release, it was confirmed that even at the targeted 1.5 degrees Celsius levels of global warming, heavy rains and flooding are likely to increase across Europe—as well as Africa, Asia and North America. Even worse, this is on the assumption that world-leading powers stay on target with cutting carbon emissions and fighting global warming—a hope that is showing signs of dwindling. The report also stated that observational data across North America, Europe and Asia shows that “human influence” is the key factor in driving extreme weather… No surprises there then.

The work that climate scientists like Bloemendaal are doing to inform us of what our planet has in store for us over the next 50 years or so shouldn’t go unnoticed. Her data indicate that Europe could see tropical cyclones—which can destroy communities, cost millions in damages and ultimately take the lives of innocent people—in our lifetime. However, despite bearing the bad news, Bloemendaal’s work could also indirectly save lives; allowing countries to prepare for the worst and implementing effective early-warning systems. Not all heroes wear capes.