Melting icebergs caused by climate change could trigger tsunamis, study suggests

Wildfires in Greece and Turkey, flash floods in Germany and landslides in Japan. It feels like the world is ending—and that’s because it is. Well, that might be a slight exaggeration, but it’s clear that the man-made detrimental impact on our planet is more tangible than ever, and that tangibility is, sadly, here to stay. Just yesterday, 9 August 2021, the UN released a blistering assessment on the state of climate change. The sobering report, claimed by the UN chief to be a “code red for humanity”, stated how it is “unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land.”

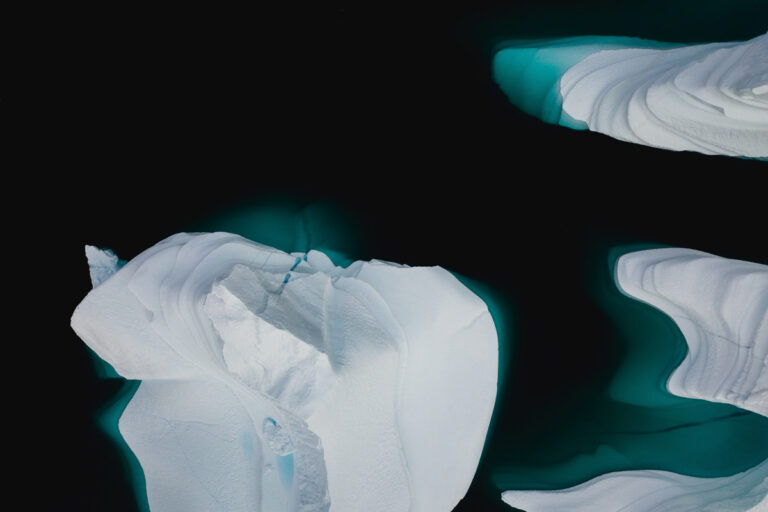

And that’s only the tip of the iceberg—what’s left of it anyway. Recent research suggests that wandering icebergs, brought about by the warmed atmosphere, could pose a significantly underestimated risk of tsunamis.

The icecaps are melting

Before we get bogged down on the details, let’s cut to the South Pole. Last May, a chunk of ice, destined to become the world’s largest iceberg, broke off the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf on the western side of Antarctica. The iceberg, named by scientists as A-76—which boasted an impressive length of 105 miles and a width of 15 miles with a square-mile diameter of 1667 (making it bigger than Rhode Island)—slid into the Weddell Sea. Despite this particular gargantuan splash, significant chunks of Antarctic ice are continuously slipping into the ocean year by year, as warming continues to contribute to the ever-more alarming climate crisis.

Icebergs can sometimes be deep enough to even scrape the seafloor, displacing a mind-blowing volume of water with their splash, which can threaten ships and damage marine structures such as platforms and undersea internet cabling. However, even smaller icebergs, which are not large enough to reach the seafloor, can produce underwater landslides when they shoreline and create a possible risk of tsunamis—according to a new study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Geoscience.

The danger of wandering icebergs

This previously under-appreciated geohazard has pricked the ears of many climate scientists as it could have implications for citizens across the globe, even for those thousands of kilometres away from icy climates. The paper thereby claimed that “Icebergs originating from the Arctic, Greenland and Antarctica are hazards thousands of kilometres away from their original source and can affect continental slopes by triggering submarine landslides.”

The insight comes from geological work that revealed an underwater landslide in the Southwind Fjord, near Canada’s Baffin Island between September 2018 and September 2019. Marine landslides, obviously, occur underwater and out of sight—making them notoriously hard to analyse. To conduct the study, scientists consulted satellite, seafloor bathymetric and local seabed composition data in a bid to solve the geological puzzle. The telltale signs of the landslide were found in a comparison of high-resolution images of the Fjord’s seabed. Iceberg pits—20 to 27 meters worth of depressions indicative of an iceberg impact—were found. This suggests that an iceberg slip was the cause behind the submarine landslide.

The new findings add to the ever-growing, and quite frankly dread-inducing, catastrophic impacts of man-made climate change on our planet. The study exposes a new marine geohazard altogether. Submarine landslides were once thought to be only caused by earthquakes—now, it seems icebergs can cause them too. The paper stated that “These results indicate icebergs grounding and capsizing may be responsible for triggering submarine landslides in many Fjords and on continental slopes in polar to sub-polar environments, representing a previously underestimated hazard.” Coastal cities, beware: as the ice caps continue to melt, this hazard is only going to grow and engulf the future in its way.