Documentary photographer Valentina Sinis tells all about the Iraqi Kurdistan women burning themselves

Photography is a powerful way in which to platform and communicate intense and complex feelings, and the people behind the lens are often some of the most emotionally intellectual individuals out there—able to capture truth in motion. Documentary photographer Valentina Sinis is one of these individuals.

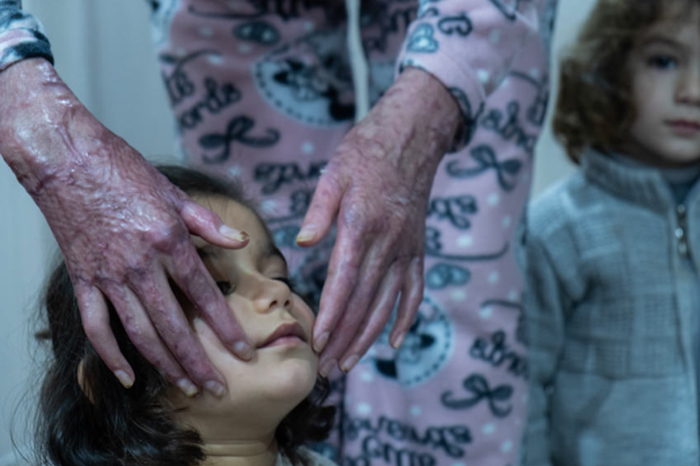

SCREENSHOT recently got the privilege of sitting down with Sinis and speaking to her about her award-winning series Broken Princess, which shared her poignant reporting on women in Iraqi Kurdistan who have been forced to resort to the desperate act of self-immolation as a form of escape from domestic violence or an expression of extreme despair.

For those of you who may not know, the act of self-immolation suicide involves deliberately setting oneself on fire as a way to end one’s life. While self-immolation suicide has been observed in various cultures over time, it is notably more widespread among the Kurdish community.

Since gaining autonomy in 1991, Iraqi Kurdistan has witnessed a troubling rise in the phenomenon of self-immolation. Despite notable progress in areas like education and legislation against gender-based violence, a significant number of Kurdish women continue to live under repressive conditions. Trapped within archaic structures, many suffer at the hands of their husbands, driving some to resort to extreme and unimaginable measures to break free.

Over 20,000 women have tragically lost their lives in what is referred to as honour crimes. Honour crimes are acts of serious violence, usually committed by male family members against female family members who they’ve decided have committed an unhonorable act. When seeking justice or protection through the legal system, victims of these crimes often encounter challenges due to potential biases that may exist within them.

Speaking with Sinis, the photographer revealed how she stumbled upon the heartbreaking stories of these women during Christmas 2018, while working on two other stories about the millennials of Baghdad, and the Iraqi LGBTQIA+ community, and was deeply moved by an incident involving a woman and her three children severely burnt due to domestic violence. This discovery led her to uncover the tragically common practice among Kurdish-Iraqi women and compelled her to bring their stories to light, shedding much-needed attention to their plight.

What drove you to document the devastating story of these women?

At the time, I was in Iraq because I was working on two other stories. When I do a story, I always live with the locals because it allows me to understand their world much more deeply. While watching TV, I had just heard a news story about a woman who had been burnt in her house along with her three children. She had arrived in the hospital alive with 90 per cent of her body damaged by flames—just in time, before dying, to accuse her husband of attempted murder. He had made it look like suicide. How was it possible that the Kurdish-Iraqi society could believe this fact?

For me, it was shocking news. I then realised that the suicide of women was a phenomenon of Kurdish-Iraqi society and that fire was the element often used. It was too sorrowful a story not to be told.

How did you approach gaining the trust of the women you photographed?

It was very difficult at first. I initially received support from the hospital in Sulaymaniyah specialising in burns. The majority of women who commit suicide there come to that hospital. When I arrived, I met extraordinary female psychologists who voluntarily offered their emotional intelligence. They were rightly defending the intimacy of these victims. I began to gain access to families and obtained the trust of the victims when they felt that I was emotionally connected with them.

Did you encounter any particular woman whose story touched you deeply?

Yes, the nature of this work and my expansive (and very Italian) temperament always leads me to maintain relationships. I have eaten and slept in the homes of the people I have had the honour of working with. These are relationships tied by threads that nothing in the world can break. I have the most intense relationship with Daroon. Daroon tried to kill herself—she is a charming, rebellious, proud, determined but also a fragile woman. She is like a character written by Jane Austen but in today’s Iraqi Kurdistan. She loves social media, sharing her photos, and she dreams of being a teacher.

Did you find any common threads among their experiences or motivations for resorting to self-immolation as a form of protest against domestic violence?

It’s a very complex question. Fire is a very special element in Kurdish culture: it means light and purification. Kurdish women also go so far as to say “I will set myself on fire for you” to bear witness to their loyalty to their beloved man. Another element is the diesel stove that is present in every house, making it a simple means to commit suicide. One thing that has always struck me is that they commit suicide at home, in most cases, when there are with other people. It is a declaration of suffering, visual suffering, shared by the people who will be forced to witness this act of this tragedy.

How did you navigate the cultural barriers that you encountered while on the ground?

For many of the families, it was an act of relief because they knew that their own story has been experienced by other people as well. Many families who gave me access to their stories were families with whom I had communicated more. In many situations, there was the husband who did not allow me to photograph freely. Trust is a process that has something alchemical and magical about it. I believe that true access is achieved when our inner perspectives as photographers align seamlessly with the inner perspectives of the individuals we are documenting.

How would you say your reporting has helped shed light on these women's situations?

I’m not a photographer who is parachuted into a reality to do a job and then leave. I choose where I want to go and what I want to narrate. For this reason, it’s essential for me to participate. If I didn’t participate, I wouldn’t even be able to make the story. 99 per cent of my work is communication.