YouTube does not consider homophobic harassment a violation of its policy

After a week of ongoing controversy, YouTube announced that it will not remove the channel of conservative commentator Steven Crowder despite his repeated use of homophobic slurs against Vox writer and video host Carlos Maza. YouTube’s refusal to take a bold stance against Crowder continued even in the face of increasing harassment Maza has suffered as a result of the unfolding scandal.

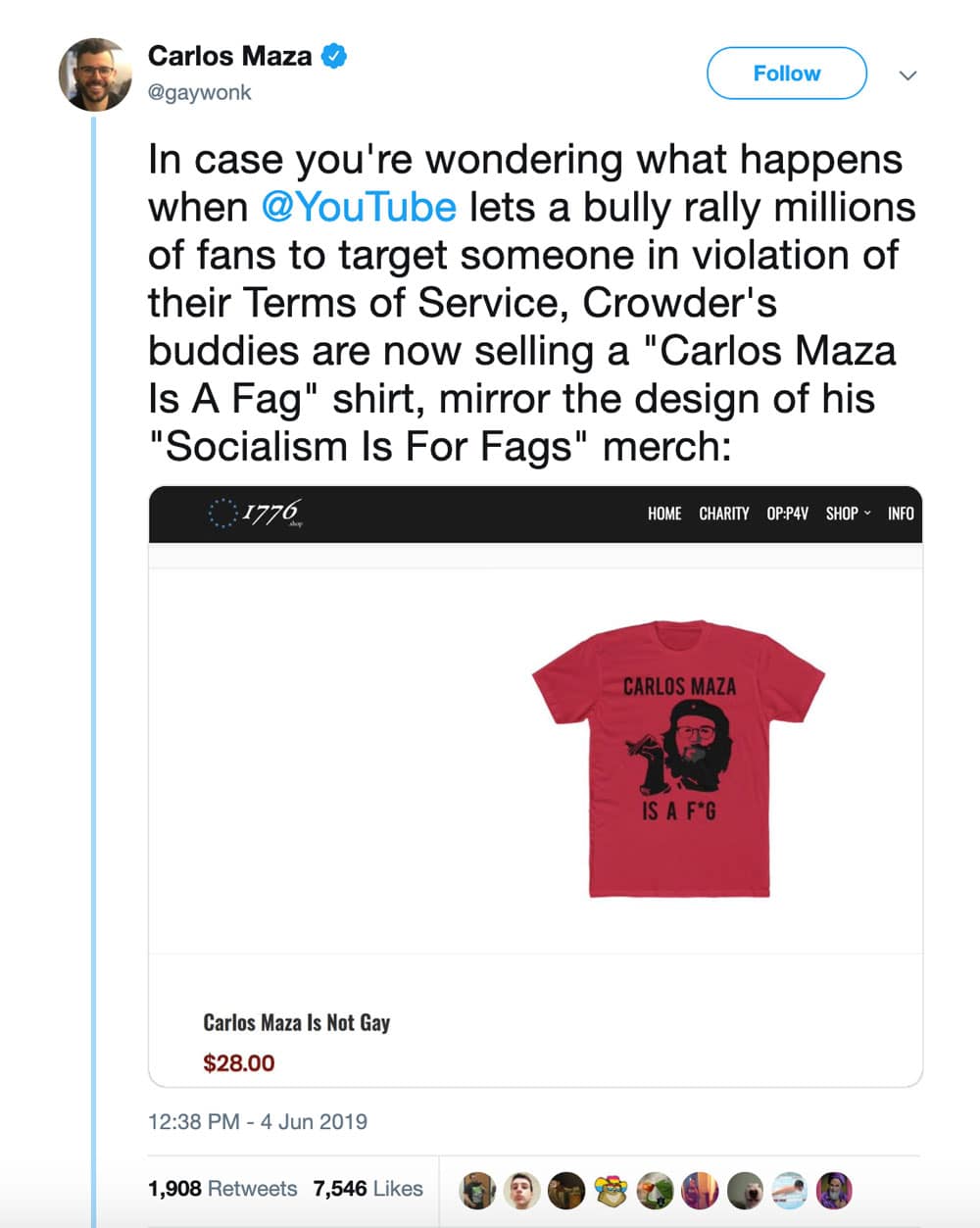

Crowder’s bullying of Maza on his channel—which currently has nearly 4 million subscribers—has been ongoing and persistent for years now, while he attempted to debunk socio-political claims made by Maza on his online Vox show Strikethrough. What Crowder referred to as “harmless ribbing” of Maza, has in fact been blatant verbal attacks on his ethnicity and sexual orientation, calling him, among other things, a “lispy queer” and a “gay Mexican”. Crowder has also repeatedly mocked Maza’s physical features and demeanour, and has gone so far as to sell T-shirts that read “Maza is a f*g”.

Although YouTube’s policy clearly dictates that “content or behaviour intended to maliciously harass, threaten, or bully,” will be taken off the platform, the company nonetheless deemed Crowder’s abuse of Maza unworthy of removal. In a tweet from Tuesday, YouTube stated: “Our teams spent the last few days conducting an in-depth review of the videos flagged to us, and while we found language that was clearly hurtful, the videos as posted don’t violate our policies.” YouTube then iterated that while they do not endorse the content in Crowder’s videos, they will not remove them from the site.

YouTube’s inaction on Maza and Crowder’s case calls for a serious meditation on the regulation of hate speech online, and exposes the great complexity of the issue.

Many arguments could be made against censoring hateful content on the web, even from a more liberal standpoint. The first challenge associated with curbing hate speech is determining what in fact constitutes hate speech. Where does one draw the line between offensive and downright hateful? This particularly becomes an issue in instances when discriminatory comments are embedded in otherwise legitimate political statements, as opposed to overtly racist slurs hurled by Neo Nazis, for instance.

Another problem involving online censorship is figuring out who should be granted the authority of classifying content as ‘hateful’. Can we trust major corporations to make these decisions for us? Again, this may be a no-brainer in cases of extreme and overt expressions of hate. It becomes more tricky, however, when it comes to speech that is more difficult to interpret. If we mandate companies such as YouTube, Facebook, and Google to be the ultimate arbiters for determining what type of content can be presented online, it may come back to bite us in the ass if companies utilise this power to censor any type of content they find objectionable or threatening to its agenda, simply by classifying it as hateful. for instance.

That said, it is important to recognise the dangerous impact of hate speech. Words matter and history is replete with examples of unabated hate speech that inspired the most heinous of atrocities.

Crowder’s case serves as a clear example of the danger of hate speech as Maza has been receiving countless harassing messages and death-threats from Crowder’s fans. And while it’s true that shutting down Crowder’s channel won’t eradicate the root cause of the problem (prevalent racism and homophobia), it sure will make it more difficult for his most extreme supporters to organise and disseminate their hate en masse.

It seems that what is desperately needed right now is a thorough and comprehensive discussion about the ways in which we could tackle and address hate speech online, while considering the various dangers in unchecked censorship.