Apple launches Apple Arcade, leaving us wondering, is it time to ‘unsubscribe’?

There’s a subscription service for everything nowadays—food and drinks: coffee (particularly Nespresso-style capsules), tea, gin, beer. For household goods: dishwasher tablets and laundry detergent. There’s even one for the sort of products you should be replacing regularly, such as razors and toothbrushes. I’ve signed up for several (perhaps too many) and have found that some are far more useful than others.

You have to use something on a regular and predictable basis in order to not run out too soon or have a dozen spares when the next package arrives. Introductory deals quickly lose their appeal when you have to pay full price, but they can also be awkward or deliberately annoying to cancel. I should know, I’ve been caught out repeatedly.

Most media is consumed via subscriptions, too. Apple Music and Spotify, Netflix, Amazon Prime, NowTV. Who still buys CDs or DVDs (strangely though there are still 2.4 million Americans who get Netflix via post in DVD format), or even purchases music to download? And in that same breath, Apple has announced that iTunes is being discontinued next month, to be replaced with Apple Music and Apple TV apps.

This week, it also launched Apple Arcade, a subscription-based games service launched on the App Store. It gives users access to dozens of games—in time, there will be over 100, with zero ads and no additional payments at any time. “How Apple Arcade Will Reshape Mobile Gaming,” reads Wired’s headline. It is offering high-quality games from established mobile gaming studios, such as Ustwo Games who produced the stunning Monument Valley. “The genres range from strategy and fantasy to absurdist golf,” Wired summarise. “Some, like Sayonara Wild Hearts, seem wildly ambitious.”

After a free one-month trial, access to Apple Arcade will cost £4.99 a month, a thoroughly good value given the range of games available, and one subscription can be shared with up to five family members. But the service goes beyond just mobile gaming—it will soon be available on Macs and Apple TV too.

Recent years have seen a shift away from paid mobile apps—remember Doodle Jump?—to free-to-play games with in-app purchases, generally to remove apps, access further content, or buy in-game currency. Here, Apple hopes to redress that, focusing on user experience without distraction.

Subscriptions give more power to the production companies, meaning they have more up-front capital and are less reliant on advertisements and gimmicks. Generally, this allows them to be more creative, experimental, and take on bigger risks. It’s what has allowed HBO, for instance, to make Game of Thrones, or Netflix to produce shows like The Crown. But it also requires these platforms to continue bashing out hit content in order to keep their subscribers. At the end of each one of those blockbuster series, Netflix, for example, loses massive percentages of its subscribers.

Subscriptions, however, fundamentally change the relationship between vendor and consumer. You don’t own your Spotify library. Netflix can remove programmes and films whenever they want, and they do so all the time. There are no guarantees, apart from their own original content, which they might cancel. Given the success and popularity of such companies over the past few years, many major U.S. networks are following suit. Friends and The Office, perennial favourites on Netflix in the U.S., will leave the platform in 2020, instead streaming exclusively on HBO Max and NBCUniversal’s streaming service.

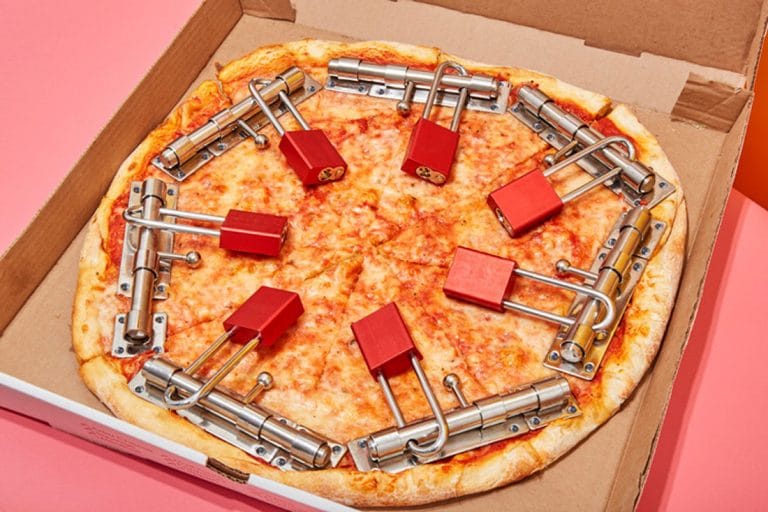

The crux of the issue is that access only lasts as long as your subscription. No matter how much money you give Netflix, they’ll never let you download and keep Friends, or Orange Is The New Black, or Glow. This isn’t even limited to purely digital systems. NuraNow offers a headphone subscription, but stresses that it is not a rent-to-own program, like many phone contracts where you end up owning whatever you rent in the first place. It seems slightly insidious, yet understandable, that any device you rent from the company remotely deactivates the moment you fail to pay an instalment.

And more services are coming. Disney+ will have the studio’s entire back catalogue of movies, as well as Disney channel programmes, original content, and the libraries of subsidiaries: Pixar, Marvel Studios, Star Wars, and 20th Century Fox. This streaming service will be big—and competitors should worry, Apple included. It is launching Apple TV+ on 1st November, promising original content from the likes of Steven Spielberg, M. Night Shyamalan, Oprah, and many more.

Paying for half a dozen different subscriptions really starts to add up, no longer centralised under Sky or similar satellite TV packages. And, without physical artefacts, you can’t share your library with friends and family. Having less ‘stuff’ (CDs and DVDs and video games) might be useful for the nomadic millennial lifestyle, but also feels somewhat empty. I find it hard to remember quite what I have and haven’t watched, while being thoroughly spoilt with choice. Perhaps it is time to unsubscribe.