A new app is being hailed as the oral Facebook from Mali

Even with the impressive internet penetration in Africa, which has given rise to an unprecedented uptake of social media, with seven out of every 10 Africans on social media sites like Facebook, the continent is still home to countries struggling with high connectivity costs and illiteracy.

In Mali for example, up to 50 percent of the population cannot read or write. This is despite 30 percent owning a smartphone. The staggering rate of illiteracy, among the highest in Africa, is attributed to a costly education system that excludes ordinary citizens, the majority of whom live below the poverty line. According to Africa Library Project statistics, 18.2 million adults cannot read or write in the country, up to 4.8 million youths between the ages of 15 and 24 are illiterate, and 3 million children eligible to attend school are at still at home.

With limited access to education, the population has been locked out of access to information and connection to the rest of the world as online platforms including social media remain largely alien. That is, until now.

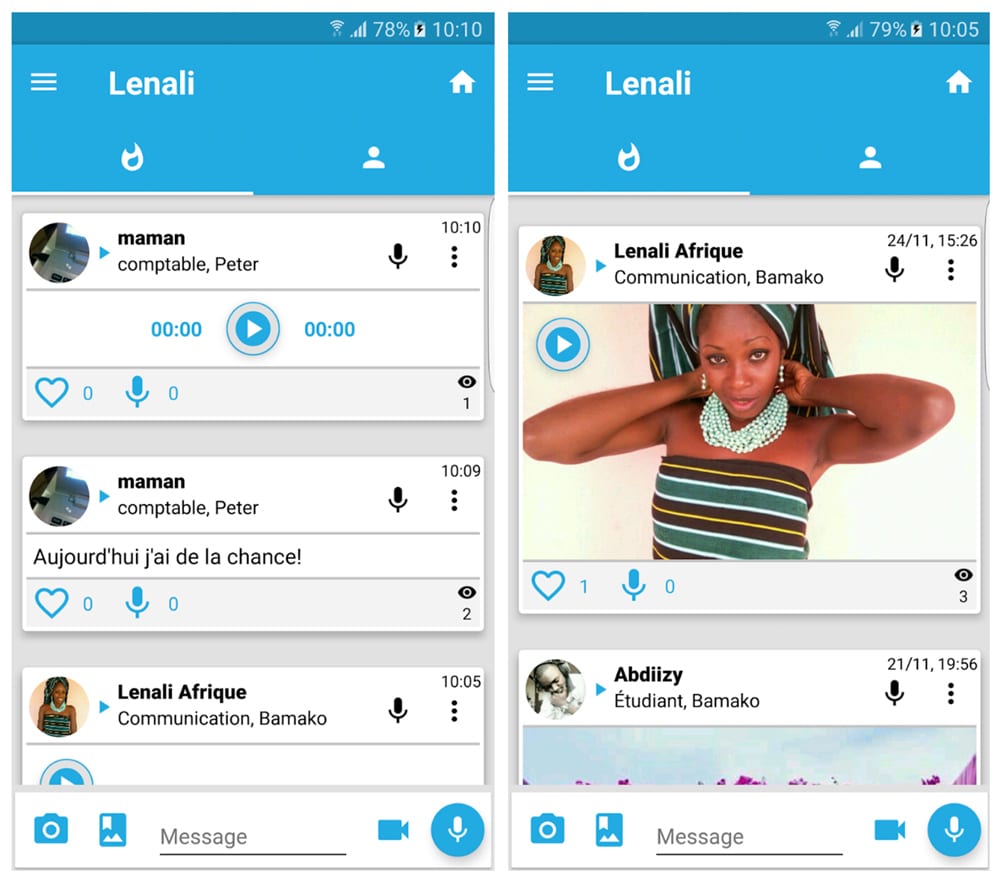

Mamadou Gouro, a 44-year-old computer engineer has come up with a first-of-its kind voice based social media platform that caters to those who cannot read. It allows users to use local languages that are predominantly used in Mali, including Bambara, Soninke, Songhay, Moore, Wolof, and French. Everything around the platform is guided by audio elements. Users even create their profiles using voice commands.

Mamadou was inspired to create the platform when a vendor in an established shop in Mali asked him to assist in translating a message that had been sent on Viber because he was unable to read. He realised he needed to do something about millions of other Malians who were struggling with the same predicament.

The application, dubbed Lenali, has already recorded over 42,000 downloads in Google Play since it first went live last year in what Mamadou attributes to ease of use and the quest by ordinary people to connect and communicate easily.

During registration, users are allowed to pick their language of choice with vocal prompts, in local dialects, directing them throughout the process—the app can even create the entire profile of a user through voice commands. When a user needs to post something, they just need to press record, speak the message then release the record button which then posts the message.

The app also has provisions that allow users to make calls and leave voice messages that are up to 59 seconds. “Since time immemorial, the African community has been predominantly oral in communication with messages passed and interpreted across generations, and this rich culture has been fast fading as technology and globalisation take effect. What the Lenali application is doing is transformative because it ensures that even with penetration of the internet in the continent we are able to bridge the digital divide while ensuring that technology finds space and place in local cultures and ultimately cultivating an online oral community,” said Maurice Mukinda, a digital strategist based in Nairobi Kenya.

To further grow the reach and language portfolio, Mamadou and his team have been working on getting key African languages into the application, including Ewé, which is spoken in Togo and Kinyarwanda, and is the dominant language in Rwanda. Mamadou believes the app has the potential of attracting a critical mass of uptakes across the continent, where spoken word still reigns supreme.

Pundits now say the app is unique to Africa and opens doors for numerous opportunities while placing the continent on the global map in homegrown innovations.

“Looking at the bigger picture we are talking about opening up the continent to opportunities like e-commerce and mainstreaming trade, especially among millions of Africans who cannot read and write but who have been driving continental trade over the decades. This has potential to build a one of its kind digital economy,” said Dr. Arthur Owiri from the University of Nairobi School of Computing and Informatics.

This article has been published as part of an ongoing content partnership with FAIRPLANET.