Virtual reality helps doctors separate three-year-old conjoined twins with fused brains

Conjoined twins from Brazil who were born with their brains fused together have been successfully separated, thanks to virtual reality (VR) and a team led by a Kashmiri-British neurosurgeon.

Bernardo and Arthur Lima underwent several operations in Rio de Janeiro under the direction of UK-based paediatric surgeon, Dr. Noor ul Owase Jeelani, from London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital. The three-year-old boys had a total of seven surgeries—including more than 33 hours of operating time in the final two alone—involving almost 100 medical staff.

According to Gemini Untwined, a charity founded by Dr. Jeelani dedicated to the research and treatment of craniopagus twins around the globe, the case was one of the most complex operations of its kind ever completed to date.

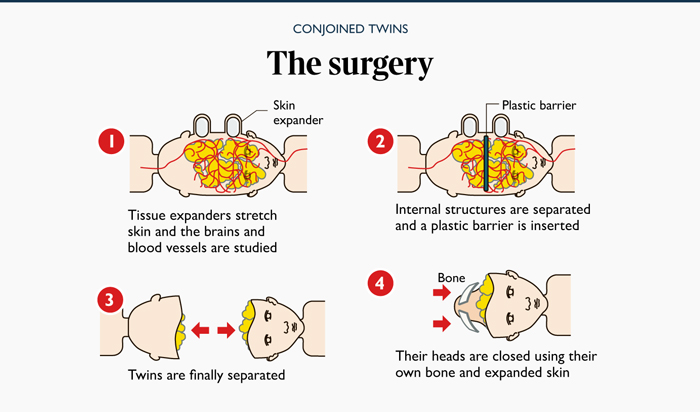

Led by Dr. Jeelani alongside Dr. Gabriel Mufarrej, head of paediatric surgery at Instituto Estadual do Cerebro Paulo Niemeyer, both experts spent months trialling techniques by using VR projections of the twins based on their CT and MRI scans. The surgeons wore VR headsets and operated in the same “virtual reality room” together—despite being almost 6,000 miles apart—allowing them to overcome any apprehension about the actual procedure.

Surgeons from @GUntwined worked for 33 hours with the team at Instituto Estadual do Cérebro Paulo Niemeyer to separate Arthur and Bernardo.

— Gemini Untwined (@GUntwined) August 1, 2022

CW: Contains surgery footagehttps://t.co/nUWZM3RN9H

“It’s just wonderful, it’s really great to see the anatomy and do the surgery before you actually put the children at any risk,” Dr. Jeelani told The Times. “You can imagine how reassuring that is for the surgeons. In some ways, these operations are considered the hardest of our time, and to do it in virtual reality was just really man-on-Mars stuff.”

The publication went on to note how Dr. Jeelani, who performs up to 300 neurosurgical and craniofacial procedures every year, said he was “absolutely shattered” after the final operation—during which he took only four 15-minute breaks for food and water. “The team’s work was complicated by the presence of scar tissue from previous unsuccessful attempts to separate the twins,” The Times reported.

Bernardo and Arthur were said to be recovering well after their blood pressure and heart rates went “through the roof” after the procedure. The expert also mentioned that the twins’ vital signs improved when they were reunited after four days and touched hands for the first time. “There were a lot of tears and hugs,” Dr. Jeelani said, adding how the family was “over the moon” with the outcome. “It was wonderful to be able to help them on this journey.”

According to Gemini Untwined, conjoined twins are quite rare, accounting for about one in 60,000 live births, with only 5 per cent of these joined at the head. The Times also reported how it’s estimated that 50 such sets of craniopagus twins are born around the world every year. Of them, it is thought that only 15 survive beyond 30 days.

“As a parent myself, it is always such a special privilege to be able to improve the outcome for these children and their family,” Dr. Jeelani admitted. “Not only have we provided a new future for the boys and their family, we have equipped the local team with the capabilities and confidence to undertake such complex work successfully again in the future.”