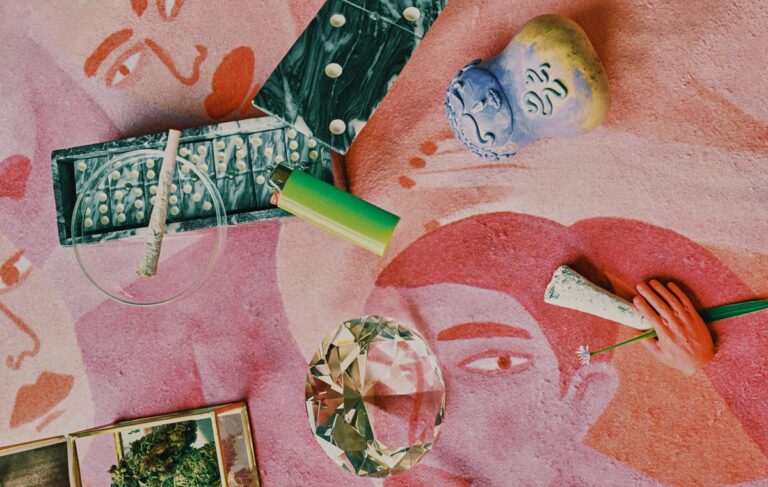

Amazon’s solution to its delivery driver shortage? Recruiting stoners

Amazon’s currently struggling with a severe shortage of delivery drivers in the US. But when it comes to next-day delivery, we all know Jeff Bezos isn’t kidding around, which is why the e-commerce giant has already found a solution, one that is surprising to say the least: it’s now recruiting marijuana users.

According to communications obtained by Bloomberg, Amazon has told its delivery partners to prominently state they don’t screen applicants for weed use. Doing so can boost the number of job applicants by as much as 400 per cent, Amazon told the publication in one message, without explaining how exactly it came up with the statistic.

Conversely, the company says, screening for marijuana cuts the prospective worker pool by up to 30 per cent. One delivery partner, who’s now stopped screening applicants after Amazon’s request, said that marijuana was the prevailing reason most people failed drug tests. Now that she’s only testing for drugs like opiates and amphetamines, more drivers pass.

While some of Amazon’s independent delivery partners are fine with simplifying their screening process, others aren’t too thrilled about its newly found stoner-friendly attitude. Understandably, there are concerns when it comes to the insurance and liability implications in the many states where marijuana use remains illegal. “They also worry that ending drug testing might prompt some drivers to toke up before going out on a route,” added Bloomberg.

“If one of my drivers crashes and kills someone and tests positive for marijuana, that’s my problem, not Amazon’s,” explained one delivery company owner, who requested anonymity because—would you look at that—Amazon discourages partners from speaking to the media.

In June, Amazon announced it would no longer screen applicants for the drug. It wasn’t long before the company began urging its delivery partners to do the same. And it looks like the company is not the only one coming up with creative ways to recruit more employees. Target announced this month that it would pay college tuition for its employees while Applebee’s offered free appetisers to applicants in its push to recruit 10,000 workers. Side note: cheers for the snacks Applebee’s but Target wins without a doubt.

Whether it truly means it or not, Amazon justified its pro-weed approach in a statement that said that marijuana testing has disproportionately affected communities of colour, stalling job growth. The company’s spokesperson also said that Amazon has zero tolerance for employees working while impaired. “If a delivery associate is impaired at work and tests positive post-accident or due to reasonable suspicion, that person would no longer be permitted to perform services for Amazon.”

According to Bloomberg, Amazon delivery contractors are often outbid by school bus companies, where drivers can make more than $20 an hour and are home for dinner. Amazon contract drivers typically earn $17 an hour and often work late into the night to keep up with demand. One solution against the delivery driver shortage would be to raise their wages. But it’s Amazon we’re talking about here.