Scientists accidentally turn gene-edited hamsters into hyper aggressive demons in experiment

A team of scientists at the Georgia State University (GSU) were left speechless after an experiment involving gene-editing on hamsters turned them into hyper aggressive little demons.

To conduct research into the biology behind the social behaviour of mammals, the GSU team used CRISPR-Cas9—an incredible type of gene therapy technology that can turn genes on and off in cells—on Syrian hamsters. They used such technology to ‘turn off’ a vasopressin receptor in the little creatures, which is the hormone responsible for aggression.

In theory, the scientists believed this would alter the social behaviour of the hamsters drastically and result in them becoming more peaceful. While their behaviour did change, it wasn’t in the direction expected.

Professor H. Elliot Albers and Professor Kim Huhman were both very surprised by the outcome, “We anticipated that if we eliminated vasopressin activity, we would reduce both aggression and social communication. But the opposite happened.”

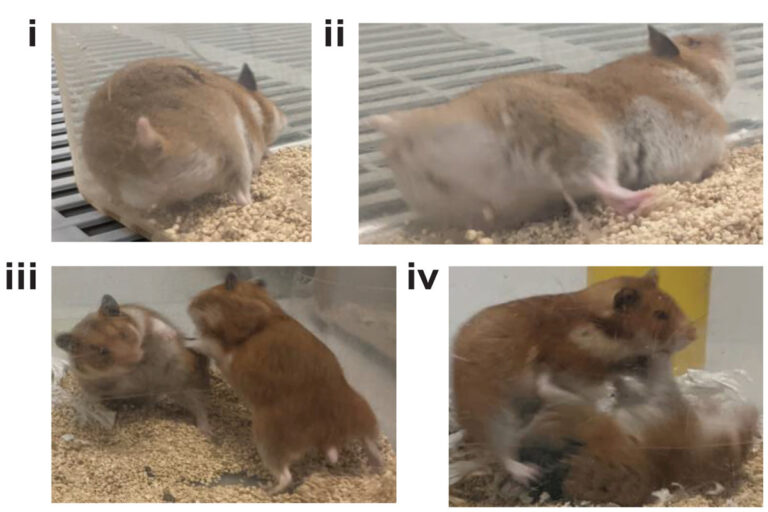

Instead, the hamsters became even more social than ever before, with their aggression towards members of the same sex greatly escalating and resulting in them chasing, biting and pinning each other down.

Albers believes this startling conclusion shows how much there is yet to learn about the biological system involved. “We don’t understand this system as well as we thought we did. The counterintuitive findings tell us we need to start thinking about the actions of these receptors across entire circuits of the brain and not just in specific brain regions.”

The use of Syrian hamsters specifically has been extremely important in understanding social behaviours, aggression and communication. They were the first animal in which the vasopressin hormone was shown to influence social behaviour. Their social organisation is much more similar to humans, which makes them the perfect research subjects, explained Huhman.

“Their stress response is more like that of humans than it is other rodents. They release the stress hormone cortisol, just as humans do. They also get many of the cancers that humans get,” she continued.

While this is a big step forward in gene editing technology, there is still a long way to go before this type of research can be undertaken on human subjects.