The Anthrax Attacks: Inside the bioterrorism events that tormented the US shortly after 9/11

Netflix’s love affair with ‘docutainment’ began long ago—with the platform currently boasting an eclectic catalogue of binge-worthy documentaries and docu-series, all poised and ready for your viewing pleasure. From Abducted in Plain Sight to Cyber Hell: Exposing an Internet Horror, there are few stories that have slipped through the cracks and avoided the streaming giant’s eagle-eyed production team. Its most recent venture, however, is none other than a thrilling documentary dissecting the 2001 US Anthrax Attacks that shook the nation, killing five people and infecting 17 others.

The Anthrax Attacks is a feature-length documentary, commissioned by Netflix, that investigates one of the worst biological attacks in US history. Through a combination of interviews and dramatic scenes, the documentary re-examines a series of Anthrax assails that took place one week after the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks.

Directed by oscar-nominated Dan Krauss and created by the BBC studios Science Unit, the documentary provides a chilling portrayal of the FBI investigation that took place following the first horrific attack on 4 October 2001.

Krauss, when speaking to the BBC, said: “This was a sprawling and massively complex story, one that required an adventurous approach in our filmmaking. The team at BBC Studios was fearless in meeting the challenge head-on, attacking every obstacle with impressive skill and care.”

The highly anticipated documentary was released on the streaming platform on 8 September 2022. But before we proceed any further, here’s all the background info worth noting.

What is Anthrax?

For those of you who may not be aware, Anthrax is a serious infectious disease caused by gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria known as ‘Bacillus anthracis’. According to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Anthrax can also be used as a biological weapon. If a human is exposed to the deadly bacteria, the Anthrax can become “activated”—causing it to multiply, produce toxins and result in severe illnesses.

What is ‘Amerithrax’?

For several weeks following the 9/11 attacks, anonymous letters laced with deadly Anthrax spores began to arrive at media companies and congressional offices across the US. From September to October 2001, a total of four letters were delivered—resulting in the deaths of five individuals, and the infection of 17 others.

Shortly after the attacks began, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) launched a search that soon became codenamed ‘Amerithrax’. The investigation lasted for almost a decade, officially concluding in 2010.

Inside ‘The Anthrax Attacks’ documentary

The Anthrax Attacks provides audiences with a detailed account of the days, and years, following the initial Anthrax assails. They reaffirm this information with eyewitness accounts from former FBI agents, Anthrax experts and members of the public—such as postal workers, scientific academics and victims’ families—who had been directly involved with the highly-publicised case.

After the first letter was discovered on 4 October 2001, public representatives immediately deemed it “an isolated incident.” It soon became apparent that this was not the case as, soon after, more letters began to arrive at both the offices of media companies and at the houses of government officials.

One individual, who had first-hand experience with an Anthrax contaminated letter, was Casey Chamberlain, an NBC news assistant from 2001 to 2007. During the documentary, Chamberlain described the moment in which she opened one of these fateful letters.

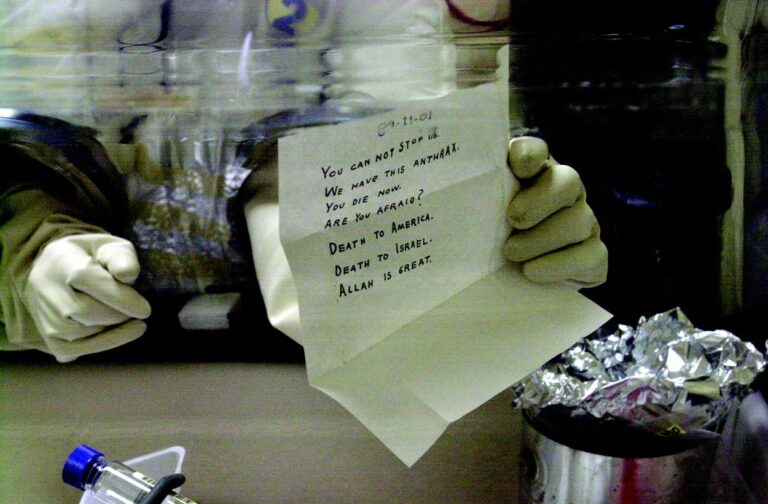

The former news assistant recalled, “I saw this letter, when I opened [it] I got chills all over. It said ‘09.011.01, Death to America, Death to Israel, Allah is great’ and inside was, what appeared to be to me, a combination of brown sugar and sand.”

Chamberlain continued: “I took the substance and I dumped it in the trash. I just was incredibly sick. I felt like there was something running through my whole body and my veins. I could’ve died easily, if I’d decided to smell the substance—I’d be dead.”

Anthrax scientist Dr Paul Keim also went on to recall the moment they realised that the anonymous letters could not have been delivered by a foreign terror group associated with the 9/11 attacks—as had been previously suspected.

Dr Keim stated, “We got the data in, and we started comparing it to our databases and it matched up with this strain we call the ‘Ames strain’. Everyone was silent, because at that point the only examples of the ‘Ames strain’, even to this day, originate in American laboratories. The person that we were pursuing was one of us.”

Now, all of this information is provided before the opening credits have even begun to roll, so you know that you’re in for a treat.

Meet Dr Bruce Edward Ivins

The documentary team then swiftly introduces viewers to our ‘leading man’: Dr Bruce Edward Ivins, who was a Department of Defence researcher at The United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). In the drama-doc, Dr Ivins is reprised by Clark Gregg—an actor most famous for playing the lovable-yet-hard-working agent Phil Coulson in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU).

Today Netflix released The Anthrax Attacks documentary which features @clarkgregg pic.twitter.com/ULArbNocxR

— ClarkGreggDaily (@ClarkGreggDay) September 8, 2022

Throughout the documentary, we’re encouraged to watch Dr Ivins and his experience when he becomes the FBI’s number one suspect. Director Krauss combines words from Dr Ivins’ personal emails alongside FBI field notes to paint a very clear picture of the shocking events in question.

A number of former FBI agents also express throughout the programme their reasoning as to why Dr Ivins appeared as the prime culprit. Both Brad Garrett, FBI agent between 1985 and 2006, and Vince Lisi, who held the post from 1989 to 2015, explained how there was a serious distrust between the bureau and the academic Anthrax experts.

Lisi explained: “One of the challenges we had was relying on the scientific community to help us in the investigation, how do we know they were not being helpful. Bruce was definitely somebody that needed to be looked at.”

After extensive testing, it was revealed that the specific strain and ‘morphs’ of Anthrax found in the anonymous letters did in fact originate from USAMRIID—the organisation where Dr Ivins worked. Morphs are the visual or behavioural differences that occur between organisms.

“Under subpoena, all of the scientists at USAMRIID, including Bruce, would have had to have gone into their collection, sampled each of their tubes, and then the FBI would send that to my laboratory for DNA analysis,” Dr Kleim explained.

“None of the scientist’s tubes had the morphs—Bruce was in the clear.”

The story of Dr Steven Hatfill

Dr Steven Hatfill is an American pathologist and biological weapons expert who quickly became the FBI’s primary suspect in 2002. His previous employment history—having been fired in 1999 for violating lab procedures and then losing a government contractor job on 23 August 2001—led officials to believe that his distrust for the government confirmed he was the Anthrax-by-mail perpetrator.

Dr Hatfill was quickly labelled as a “Person of Interest” by multiple news sources and public figures, leading to extreme media surveillance, also known as “in-your-face harassment.”

Tom Connolly, Dr Hatfill’s attorney, expressed in the documentary: “The FBI engaged in a campaign with their friends in the press to continue suggesting to the American public that Dr Hatfill had committed this offence. They did so without any evidence because they were happy to have a patsy to suggest to the public that ‘we’re making progress’.”

Dr Hatfill was ultimately ruled out of the investigation and, as reported by The New York Times, in 2008 he received a $4.6 million payout from the Justice Department in order to settle a lawsuit the expert had filed in 2003 after he claimed that the irresponsible news coverage based on government leaks had ruined his scientific and personal reputation.

The big reveal

Now is your chance to tune out if you’re planning on watching The Anthrax Attacks—spoilers ahead.

September 2006 rolls around, and—as explored in the documentary—the investigation is given a new lease of life, and thanks to an “incredibly aggressive development of the science,” new discoveries were made into where the original Anthrax spores had originated from. These new scientific methods however, were costly and Dr Keim and both of the FBI agents involved in the documentary process revealed that this was the most expensive FBI investigation ever pursued in the bureau’s history.

Through the means of further scientific testing, and extortionate quantities of funding, the team of scientists were able to trace the mailed spores back to one individual… Dr Bruce Ivins. Dun dun duuun! Naturally, this discovery—while helping the investigation—failed to provide enough concrete evidence to convict Dr Ivins of the biochemical attack.

The remainder of the documentary delves deeper into the psychology of Dr Ivins, his idiosyncrasies and his personal relationships with a number of women or, as he would call them, “secret sharers.” Specifically, we get a closer glimpse into Dr Ivin’s online, shall we say, correspondents.

“Crazy Bruce” had a number of obsessions, one of which was Kappa Kappa Gamma (KKG) sorority. Having developed an interest in the 1960s during his college years, Dr Ivins was rejected by a girl from KKG and subsequently became consumed with the group of women. Later on in life, Dr Ivins would invent multiple personas and pose as a KKG sorority sister online.

In one particularly-alarming dramatic recreation, Dr Ivins is sat with one of his “secret sharers”—who is wearing a wire so as to cooperate with the FBI—and they discuss his state of mind.

When asked by the woman if he did indeed send those poisonous letters, Dr Ivins responded, “I can’t recall doing anything like that. The only thing I know for sure, is that in my right mind I would never hurt anyone.” That doesn’t sound too convincing, Bruce.

Following this, Dr Ivins, having suspected that he was going to be arrested for the bioterrorism attack, began withdrawing from his friends and family.

In his personal emails, Dr Ivins expressed feelings of depression. “I have this terrible dreaded feeling that I have been selected for the blood sacrifice. The FBI can take the most innocent moment or incident and turn it into something that looks as if it came from the devil himself,” he stated. “I don’t have a killer bone in my body but it doesn’t make a difference.”

The USAMRIID researcher continued: “I miss the days where I felt we were doing what was worthy and honest. Our paths shape our futures, and mine was built with lies and craziness and depression. Go down low, low, low as you can go and then dig forever, there is where you’ll find me.”

On 29 July 2008, Dr Ivins died following a drug overdose.

Looking back

A number of the interviewees featured in the documentary were conflicted over whether or not they believed Dr Ivins was 100 per cent guilty of the Anthrax attack murders—and whether or not the FBI was to blame for contributing to his depression and subsequent suicide. Despite all of this, the investigation was formally closed on 19 February 2010.

The most crucial takeaways from The Anthrax Attacks is the testimony given from the postal workers about their personal experiences after being exposed to the infectious disease at work. A number of the workers expressed their frustration with their managers being so haphazard and negligent in regards to employee safety.

Terrell Worrell, a former postal worker from Washington DC, told the filmmakers: “They say there were five deaths, 17 people got sick. No, they don’t know how many people—my X-rays show that my lungs look like I’ve been a heavy smoker, or I have a lung disease. I’ve never smoked a day in my life.”

In 2002, the Brentwood Processing Distribution centre was renamed as the “Joseph P. Curseen Junior and Thomas Morris Junior Processing and Distribution facility” in tribute to two of the postal workers who lost their lives to Anthrax inhalation.

Worrell signed off the documentary by stating: “I think different people walk away from this with different things, and I think we’re still learning from the experience.”