The surprising life of Bob Ross prior to ‘The Joy of Painting’

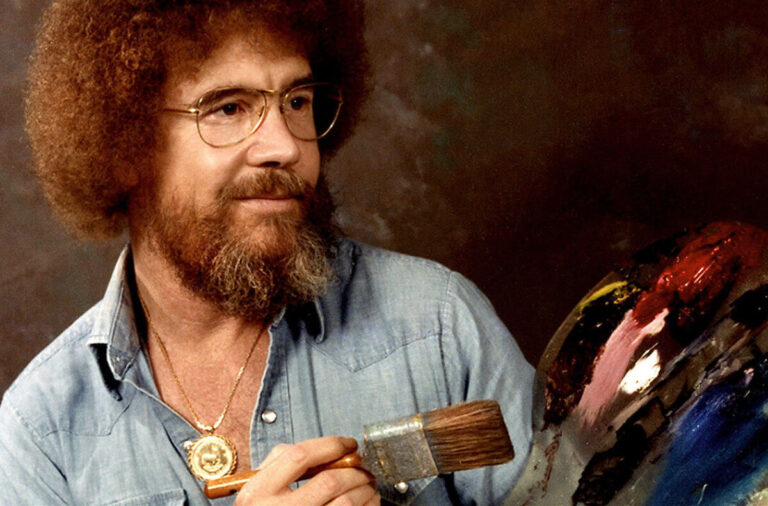

If you tuned in to the BBC when the pandemic hit in March 2020, you might’ve come across a man with an impeccable perm, narrating softly while painting a serene Alaskan mountain range—a place you probably wished you were when trapped in the confines of your living room. That man is Bob Ross—arguably the most iconic, and definitely the most recognisable, painter of the late 1900s.

Thanks to becoming somewhat of a meme on Twitch, the man has gained rapid internet popularity from his show The Joy of Painting, which ran for 31 series from 1983 to 1994. His iconic persona and art style has enchanted generations—but how did this man come to be? I’ve dug through the history books to find out how this iconic man came to be, and the legacy he’s left behind.

The early years of Bob Ross

Take a look at his art and you’d assume Bob Ross was born in Alaska, Canada or, at a push, maybe a remote cabin in Idaho? The truth might surprise you. Robert Norman Ross was born on 29 October 1942, in the beach-side city of Daytona, Florida—a world away from his scenic landscape paintings of iconic mountainous arctic tundras.

Ross by no means had a rags-to-riches story, he actually enjoyed a fairly conventional 1950s American upbringing. His dad was a carpenter and, for a short time, Ross spent his formative years working in the family business. However, on one fateful day, a tragic accident where Bob lost a part of his index finger while working changed everything.

If there’s anything to prove that the butterfly effect exists, it’s this. When life gives you lemons, just think of Bob—everything happens for a reason. If it wasn’t for Ross losing part of his finger, he wouldn’t have become the man we cherish today and would’ve most likely stayed a carpenter making (probably quite aesthetic) furniture for the rest of his days.

Bob Ross’ career in the military

But he didn’t continue making furniture. In fact, the accident led him to throw in the carpentry towel and search for a career change. That change was for the Air Force, which he joined in 1960, marking a new chapter in the artist’s life.

While stationed in Alaska, Ross discovered his passion for painting—taking a number of classes outside of his working hours. However, he found himself at odds with many of his painting instructors, who specialised more in abstract painting. The very man himself told The New York Times, “they’d tell you what makes a tree, but they wouldn’t tell you how to paint a tree.”

Now, I can’t tell you for certain what went on in these art classes but gathering it was the 1960s, it wouldn’t be past the realm of possibility that they dabbled in a few drugs to unleash their artistic spirit. Mind you, Ross was in the Air Force at the time, which perhaps explains why he rallied against the more abstract aspect of painting—I doubt LSD and flying fighter planes would’ve been a great mix.

It wasn’t before when Ross discovered wet-on-wet, or to put it in fancy art terms ‘alla prima’, oil painting that he really found his artistic stride. Ironically, Ross was taught this type of painting—now his iconic style—by a German painter called Bill Alexander who hosted his own show The Magic of Oil Painting in the 1980s. Little did Ross know at the time, he would go on to host a cherished art show of his own, binged by millions of millennials on Netflix for generations later.

Ross fell for this style of alla prima oil painting, mastering his technique by capturing and flogging his Alaskan surroundings painted on gold-mining pans. Eventually, he made such a name for himself that his income from art surpassed his military salary and he was able to retire from the Airforce in 1981.

It sounds like the Air Force was never for him anyway. According to the local newspaper the Orlando Sentinel, his role required him to be aggressive and authoritative, out of character for the sweet hippie-looking, afro-rocking man we know and love. He told the Sentinel he was “the guy who makes you scrub the latrine, the guy who makes you make your bed, the guy who screams at you for being late to work.” The day he left the military, he vowed never to raise his voice again. This explains his soft, soothing and monotonic voice—ah, talk me to sleep, sweet Rossy.

Hosting his own show

The origins of his debut TV show, The Joy of Painting, is elusive as his iconic dress sense, permed hair and artistic talent. Please, if you do know how he made the jump from canvas to television screens, let me know. From digging through the archives, what I can tell you is that when he left the Air Force, he worked for Alexander Magic Art Supplies Company (remember the German guy who ran his own painting show? He also owned that company). I’d like to think of their relationship as the Padawan (Ross) and the Jedi (Alexander).

In this scenario, the Padawan definitely did become the Jedi—in fact, he surpassed the Jedi. While leading one of his art tutoring lessons for Alexander Magic Art Supplies Company, he was convinced by one of his students Annette Kowalski to start an art business of his own. She, along with Ross and his wife, pooled their savings to start it together, which blossomed into The Joy of Painting that is enjoyed to this day.

It was a risky move and they struggled at first—but it paid off. Now, Ross’ international fame has made his style, perm and personality recognisable across generations. He’s painted over 30,000 pieces—a collection that’s likely priced in the multi-millions. With so many of these paintings out there, it’ll be easy to cop one yourself right? Nope. Kowalski holds the keys to the stash of paintings and doesn’t plan on selling them anytime soon, it’s not Ross’ style.

And there you have it, the mystery of Bob Ross unveiled. I’m sure there’s a lot I’ve missed, after all, a single article can’t cover such a successful artist’s entire life. However, I hope I’ve given a decent summary of how the legend came to be. Unfortunately, like all things in life, everything must come to an end. Although Ross sadly passed away from lymphoma at the age of 52, his perm and persona lives on and will continue to touch the hearts of many for years to come.