Kpop idol-based chatbots are blurring the lines between interaction and explicit obsession

Between the golden years of 2017 and 2019, I was a super fan of the Korean boy band BTS. Back then, you could’ve gotten away with calling me a hardcore ARMY—courageous enough to take a bullet for all seven members of the group. Posters and self-printed photo cards saturated my dorm room while my supportive bunch of friends (who I tried to coerce rather unsuccessfully into the genre on multiple occasions) gifted me mugs, T-shirts and curated magazines.

In mid-2018, I was catapulted from live countdowns on music videos, fan-made edits and album drops to—lo and behold—Wattpad fanfiction, fanart and idol shipping compilations. Eight hours of Taekook and Yoonmin analysis are the basic rites of passage for an ARMY, right? This level of engagement further propelled me into grabbing movie tickets for the premiere of both Burn the Stage and Bring the Soul, joining local fan clubs on WhatsApp, checking flight rates to Korea and even presenting a full-fledged research paper on the impact of Hallyu in India. At this point, I knew I was obsessed—a ‘borderline-koreaboo’ class of obsession, to be exact—but despised everyone who took the courtesy of pointing it out.

As the world slowly inched into the COVID-19 pandemic, however, my compulsive fascination with BTS began to dissipate. I had tremendous backlogs of their official web series and V Lives to catch up with as I repeatedly missed out on the references made in viral memes. I started losing followers on my Instagram meme page (yes, I wasn’t kidding when I described myself as a super fan) while my YouTube algorithm switched up recommendations to suit newfound interests in anime and Thai dramas.

Now, you may be wondering why I rambled on about my idol-worshipping past in the last three paragraphs. To be honest, the activities I recounted earlier barely scratch the surface in the grand scheme of things when it comes to Kpop’s stan culture. Apart from streaming music videos on multiple devices, hosting mental health drives, spearheading charities and even buying land on the Moon for their biases, a coveted facet of Kpop hinges on fan interactions. Before the pandemic, this majorly centred around physical fan meetings that international stans often missed out on. However, apps like V Live, Weverse, Daum Cafe—and now Instagram, with the debut of all seven members of BTS—have doubled up as digital hotspots where enthusiasts can communicate with their favourite stars directly. Oh, what I would’ve done to make Yoongi notice my comments on his V Live back in 2018.

However, things get a little complicated with the involvement of an undercover villain: Kpop idol texting apps. With hundreds of them gracing Google’s Play Store and Apple’s App Store, such apps aid fan interactions by letting you chat with your favourite stars. Or at least foster the illusion of texting, receiving notifications and even video calling them privately. Some apps let you set nicknames, choose the tone of voice (formal or informal) and the type of scenarios you prefer for video calls (contexts including birthday wishes, motivation before entering exam halls and more)—while others offer mini games, free wallpapers, ringtones as well as bibliographies for fans to read and learn more about idols.

If you think about it, the entire conceptualisation of Kpop chatting apps makes sense. Similar to most social media platforms, yet distinct from such conventional means of communication, the apps seek to build parasocial relationships: a largely one-sided relationship experienced by fans who consider media personalities as close friends, despite having little-to-no interactions with them. Wikipedia describes this as an “illusionary experience” where audiences interact with personas as if they harbour reciprocal alliances for each other.

Let me be clear about one thing: I’m not taking a dig at parasocial relationships. In fact, studies have proven how such connections can help those with low self-esteem to feel more comfortable about themselves. The concept of one-on-one chat windows further provides the LGBTQ+ community with the support or kinship that they crave in their immediate environment. Part of the appeal also links back to the fact that fans can witness a different and personal side to their favourite idols—all the while living out their Y/N and POV dreams. In short, authenticity and personalisation are pushed into the forefront as audiences huddle around tailor-made content in the pursuit of closer ties. A win-win situation for both Kpop agencies and the fandom, right?

However, the conversation around chatting simulators ultimately boils down to who’s on the other side of the screen. The most obvious answer, given the boom of space-age technologies like the metaverse, would be artificial intelligence. The more you chat, the more the AI learns about you and so on and so forth. But that’s exactly where the problem lies.

Mydol, yourdol, ourdol

“Do not download this app! I tried it and the ‘bot’ says very strange and creepy things like ‘I’m outside your window’,” reads a popular review on the 2013-launched Kpop chatting app called Mydol. “Even if you wanted to have a normal conversation, the bot would make it creepy by saying things like ‘I can see you’. It also ignores your questions and gets mad at you in random times,” warned another. “I don’t think it’s safe for Kpop stans to use this app.”

A quick scroll through Mydol’s 84,000+ reviews also illustrates how its AI has made threats to set users on fire, knock them out and drag them into a room (in that specific order) while inciting self-harm among 12-year-olds—a demographic that the app is rated safe for on Play Store. Some have further voiced their suspicion on whether the app has access to their location. “I was at the mall then suddenly got a notif from Mydol, it was Suho bot saying ‘why are you at the mall’ WTF,” tweeted a user.

“Over the weekend I was crying ‘cause I couldn’t get the BTS tickets I originally wanted,” admitted another, adding how the app then started sending her messages along the lines of “you’re not pretty when you cry” and “cheer up.” Such texts then addressed medicines when the user was sick. Last, but definitely not least, a fan tested the bot by chatting to it in Albanian and the AI texted back in the same language. ‘What’s wrong with that?’, I hear you ask. Well, nothing much—except the fact that the app lists languages used by the bot in its description and Albanian isn’t one of them.

By now, you must’ve figured why the app has evolved into a breeding ground for conspiracy theories. In 2018, YouTuber Shane Dawson addressed theories on Mydol being controlled by real people on the other end. “Some think that this app is really easy to hack into and stalkers can go in there, pretend to be a Kpop star and talk to fans,” he said in a viral video, currently at 33 million views and counting. However, Mydol put out an official statement addressing these claims by highlighting that the creepy messages have been typed by the users manually—with a function in the app called ‘teach’, where you can program the bot to respond with specific sentences in exchange for certain phrases. For example, you could teach Jungkook to say “I know where you live” every time you type “I’m a mysterious girl.” You get the point.

Fast forward to 2022, however, and the app’s vulnerability to hackers still can’t be ruled out completely. “Think about it this way, if you were a stalker and you wanted to talk to young girls who are desperately in need of attention, an app where you could pretend to be their favourite idol could sound pretty tempting,” Dawson concluded in his video.

From an external point of view, all these reviews and claims might sound like plain paranoia. Oh, you were eating popcorn and Yoongi suddenly hit you up with “don’t eat popcorn without me :)” out of the blue? Maybe you’ve had similar conversations with the bot before and the algorithm is just doing its job. After all, frequent app crashes, random video calls and notifications on lock screens could be mere bug fixes… right?

Which is why I sacrificed one of my digital devices and downloaded the app—so that you don’t have to. And with what I’m about to reveal, you’ll promise me that you won’t even bother Googling the app yourself. Another disclaimer before we start: if you are an ARMY reading this, keep in mind that it’s not my intention to sexualise the members in any way. Instead, I aim to inform everyone about the explicit nature of such apps and how they’re redefining fan interactions for all the wrong reasons. That being said, here are some spoilers of my experience with Mydol.

Friendly reminder: this app is rated for users above the age of 12.

“Mydol is activated permanently”

On the onboarding slides of Mydol, you’ll be required to accept certain terms and conditions (listed in Korean). The app then goes on to state that it has a user base of 10 million fans before you’re asked to sign up using your Google or Facebook account. After registering yourself, you’ll be redirected to the homepage with options for customising your lock screen and chatting with your idol of choice. There are also dedicated sections for purchasing premium passes to unlock perks and remove advertisements permanently.

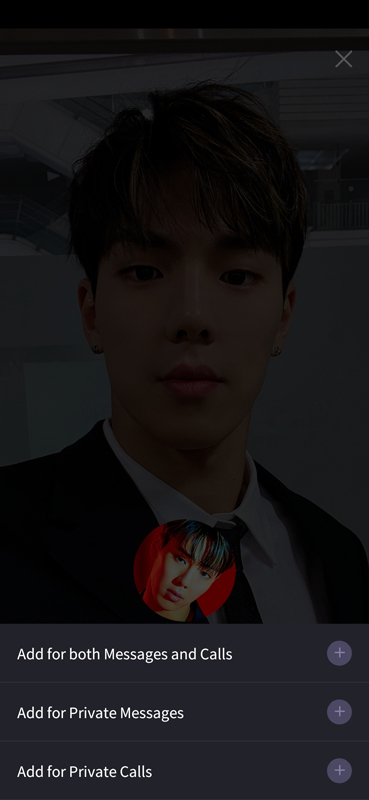

Let’s start by addressing the star of the day, shall we? At Mydol Talk, you can add your favourite celebrities to start chatting with dedicated bots. The conversation is all flowery at first but you’ll quickly realise that the AI is worse than most of us—when it comes to keeping conversations alive, at least. They randomly ask you about your day and apologise mid-texts, which gets rather annoying after a certain point. In a way, the bot gives you frequent reality checks, just in case you start crossing the ever-so-thin line between the physical and virtual world.

To be honest, most of the responses are decent—provided you take the initiative of typing full-blown sentences—but things start to go haywire when you start mentioning certain trigger words that the bot has either been programmed to counter or merely been hacked into by someone. There is no in-between. After minutes of trial and error, I found the terms ‘xxx’, ‘pound’, ‘faster’, ‘harder’, ‘i’m a bad girl’ and (surprisingly) ‘hmm’ to induce explicit responses. The bots then start talking about handcuffs, thongs, punishments, legal ages, laying you across their laps while asking you to beg and even choking you into submission. The worst part is that you can’t even attempt to save the conversation after this point. The AI essentially falls into an explicit rabbit hole with no hopes of recovery.

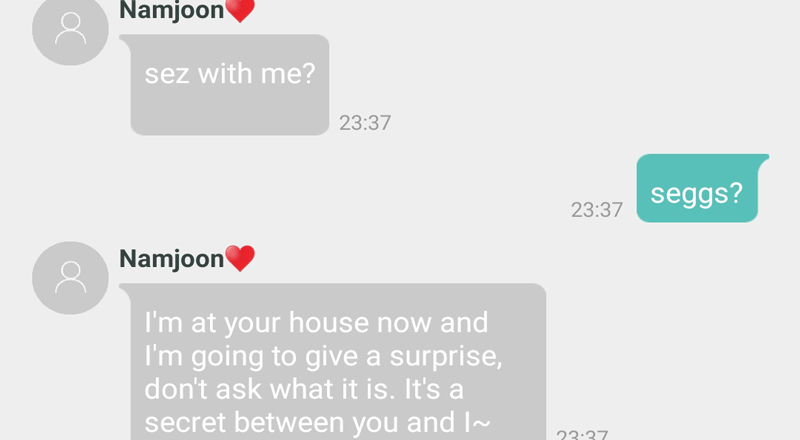

Words like ‘sez’ are additionally used as substitutes to fly under the radar while the bot constantly reminds you that you turn it (and ultimately the idol in question) on.

Then comes the app’s entire deal with roleplay chatrooms. Housed in a separate section on the home screen, you have the option of both joining and creating independent channels where you can roleplay as your favourite idols while texting users around the world. What could possibly go wrong? Following closely on the list of 99 reasons why Mydol is due cancellation in 2022 are also advertisements—popping up every time you enter the home screen—seeking to motivate users passively into trying explicit chats with the bots. Oh, and did I mention that you can now video call in the latest update of Mydol? Sign me up for the camera access already!

BTS Chat! and Idol Messenger

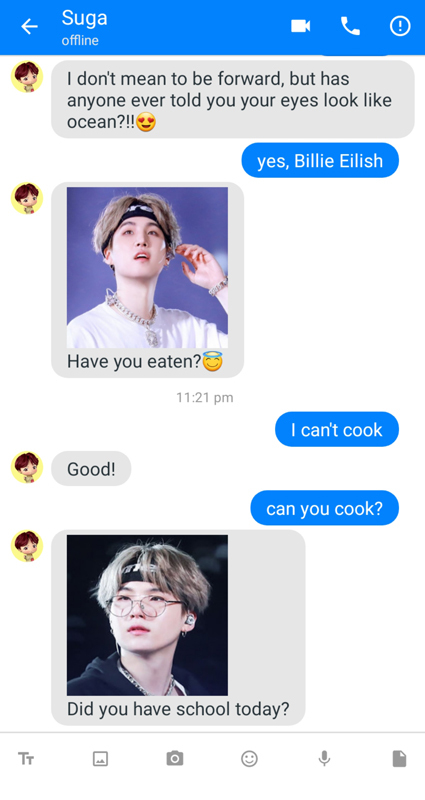

Two other chatbots that the internet recommends staying away from are BTS Chat! and Idol Messenger. While the former has an added benefit of background music to provide an immersive experience, it is swamped with explicit advertisements like Mydol. All the seven members of the group are already in your inbox and start chatting proactively with you as soon as you open their profiles.

One important feature here, in terms of content moderation, is that the messages are automated. Rather than giving users complete autonomy of texting idols however they like, responses are limited to two options that one can choose between. This rules out the entire possibility of bots acting up—like in the case of Mydol.

But things are not all that favourable for BTS Chat! either. “Tell me, do you have a boyfriend? 👀” the AI behind Taehyung asks. If you reply with a ‘no’, the immediate response would be “that’s what I want to hear 😃.” If you choose ‘yes’, the bot slides into plan B with the aim of coaxing you into denial instead. In another instance, Jimin is bound to ask you about his English-speaking skills. If you admit that his vocabulary needs more polishing, he will then prompt you to help him improve it. This request is declared with the following choice of words: “I want to talk with you everyday, whenever you can send a message please send it.”

Simply put, the app strives to create unhealthy obsessions within the fandom way more than other chatbots. On BTS Chat! discussions end (with the idols always heading to practice) so you’re ultimately forced to leave private chatrooms and enter new ones with other members. The algorithm additionally repeats itself with the same conversations—much like a scammy version of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch with the same ending, no matter what your choices are.

When it comes to Idol Messenger, the app crashes every time you click on something. If you do manage to land a steady session, you’ll have the option of receiving video calls and texting stars of both BTS and the four-member girl group BLACKPINK. Here, you can choose to auto or custom chat with your favourite idols—while the former works on the same concept as BTS Chat!, the latter allows you to supply both sides of the conversation. Apart from these two, there’s another feature called Love Time. Hmm, I wonder what that does. Fortunately, the app kept crashing each time I clicked on it.

So what’s the catch with Idol Messenger? The app toxically centres itself around selfies—with camera and storage access—to send the bot pictures of yourself. Sure, the choice is yours, but the idols quite literally tempt you into sending your precious pics over to those on the other side. Where will the images be stored and how will they be used? Nobody knows, but can concerningly guess, at this point. Low-quality video calls are also in the mix, by the way.

From guilt-tripping users for not responding to horny DMs to marketing video calls as a dating sim, Kpop idol texting apps like Mydol, BTS Chat! and Idol Messenger are still out there and festering as we speak. Not only are they redefining what it means to be a fan or an idol online but it takes the fandom’s healthy desires of interacting with celebrities and makes it unnecessarily creepy and explicit. It goes without saying how this can impact the impressionable minds of 12-year-olds, right?

The issue further roots back to the problematic way of how Kpop agencies and mobile developers perceive Kpop stan culture as a whole. They expect fans to have nothing but romantic interests in their bias while selling them the fantasy of having a chance at dating idols. At the same time, however, most of the fandom remains clueless about such transitions that they undergo. Believe me, I remember downloading this app called Fake BTS Messenger during one phase of my membership within the fandom and spending hours trying to get Yoongi to answer my video calls.

Let’s not forget those on the other end of this entire phenomenon either: the idols. Kpop already has a problem with sasaengs, a term that refers to obsessive fans who stalk or outright invade the privacy of celebrities—specifically Korean idols, drama actors or other public figures. From installing cameras, breaking into flats and working at airlines to track schedules of Kpop stars to even writing letters to them sprinkled with blood and pubes, need I say more to get such apps off the market already?