Opinion

Climate change therapy: a flying shame

By Eleanor Flowers

Opinion

Climate change therapy: a flying shame

By Eleanor Flowers

Published May 22, 2019 at 05:00 AM

Reading time: 3 minutes

Climate change

May 22, 2019

“I feel so guilty.”

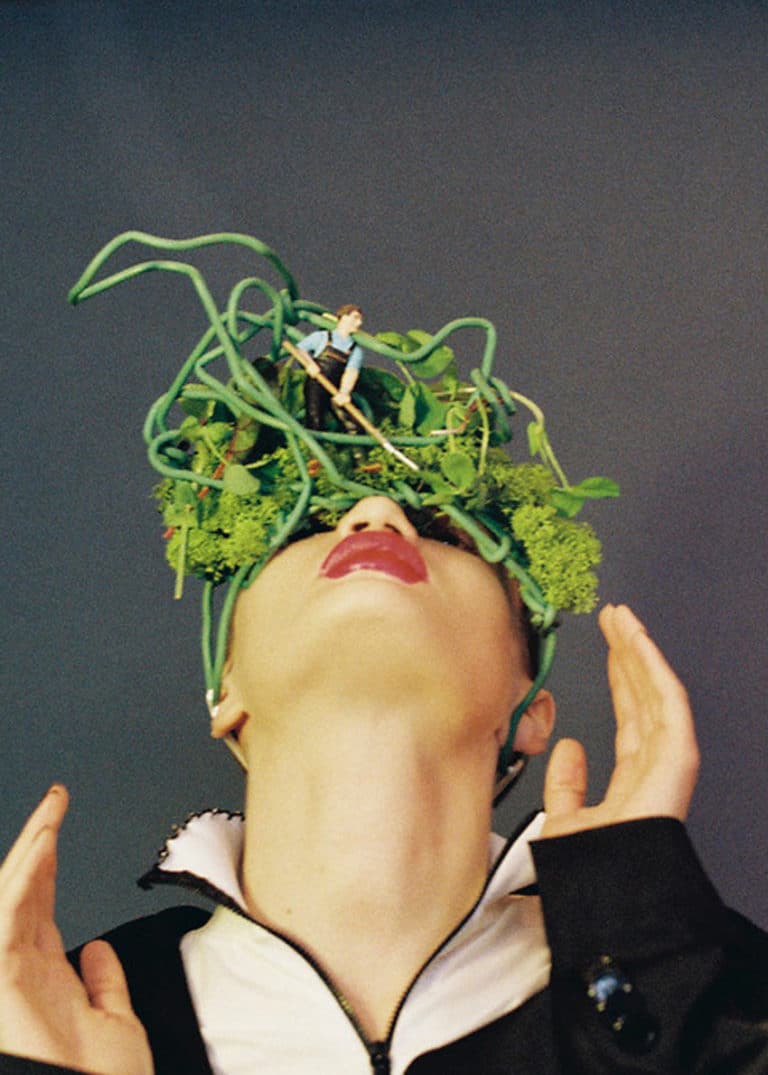

I’m on a video call with a friend, let’s call him Sid, who works as cabin crew for a major airline. He’s generation Z and has a plant-based diet. He tells me he tried to eat scallops the other night when he landed late in France. He couldn’t do it, felt too bad. Instead, he picked at the carrot puree underneath and forgot about the seafood. Sid feels bad about consuming animal products, and about contributing to food waste, but he feels worse about his carbon-intensive job. It’s an inescapable web of shame.

“I do feel guilty that flying is just doing so much damage. I always think, when we’re coming into land and we have to wait for half an hour while we loop around a holding pattern…how much fuel is this burning?”

Sid wanted to vote for the Green Party in the upcoming European Parliament elections, until he heard the party recommend that people limit themselves to one flight a year. “I just can’t get behind that”, he sighs.

Taking climate action means readdressing the foundations of our identities. It starts with flying. When I was growing up I was told that travelling would make me a well-rounded, employable person. I was promised that the only way to truly understand a culture or to learn a language was by jumping on a plane to whichever destination I felt inclined towards. If there were one thing I knew I wanted when I grew up, it was to feel the glamour of being a frequent flyer. It was the narrative of the educated and of the well-to-do. Arriving by plane makes any entrance grander. Planes make people feel important.

Now the narrative has, rightly so, shifted dramatically. Our educated friends in Sweden have begun a phenomenon called ‘flygskam’ or ‘flying shame’. Social stigma in Sweden surrounding flying has led to a sharp drop in the number of aeroplane passengers in recent months, prompting airlines to up their efforts to reduce emissions, or at least pretend to, as all the best green-washing corporations do.

I’m not here to talk economics, although the sheer financial fuckery of a world where rich people have decided flying isn’t cool anymore hits me when Sid suggests I Google ‘flightradar24’. It’s a web tracking tool which shows all the flights in the world in real-time. Thousands of pixelated yellow planes shuffle and stutter over a green and blue map of the world. It’s astounding to think of all those goods and people above us, whose livelihoods depend on fuel-guzzling jumbo jets.

Climate change is hard for Sid and I to talk about. I’m a climate researcher with the luxury of taking the moral high-ground because my job allows me to do so. Frequent flying has been a part of my social makeup, but I’m leaving it behind. I’ve stopped taking weekend trips and city breaks that rely on short-haul flights. Where I can, I take the train, even though it is often more expensive to do so. I console Sid by telling him I had a beef roast the other Sunday.

I ask him, aside from guilt and shame, how the recent school strikes and Extinction Rebellion protests made him feel. He tells me that during the protests there had been a rumour one morning that activists were going to chain themselves to the runway. As Sid belted himself in, ready for take-off, he prayed silently for the activists to go ahead and lie down on the tarmac to halt the take-off. I see that the idea of just one day without flights emissions from Heathrow fills him with a feeling of relief and hope. Sid’s colleagues apparently grumbled at the protests, found them pesky, but I wonder how many of them also turned secret wishes for the environment over in their minds as they ascended towards the sky.

This week, climate activist and journalist Naomi Klein tweeted powerfully in response to Democrat Joe Biden’s plans to craft a middle-ground climate policy: “No Joe, there is no ‘middle ground’ on climate breakdown—there is bold, transformative action or there is sinking ground, burning ground and churning ground.”

There is no middle ground. We have to change today, but that means continuing to open up dialogue, especially with people whose jobs prevent them from taking the type of climate action they’d like to. If we can’t have middle of the ground solutions then perhaps we can have middle of the ground listening. Sid’s grateful for the climate strikes, if activists hadn’t taken bold action, he points out, we wouldn’t be having this difficult discussion.

Shame locks lips and stifles empathy. Shaming is often a pastime of the most privileged. For many, it’s not that they won’t change, it’s that they can’t, yet. Sid loves the earth, but he loves his livelihood too. It’s not about greed for Sid, it’s about putting plant-based food on the plate.