Mel B’s new short film comes after ‘disappointing’ Domestic Abuse Bill. What more needs to be done?

A few days ago, Spice Girls veteran Mel B (real name Melanie Brown) shocked the internet with a harrowingly important video about domestic abuse. As a patron of Women’s Aid, Mel collaborated with composer and award-winning film director and composer Fabio D’Andrea as well as choreographer Ashley Wallen to create the short film Love Should Not Hurt. The video narrates the journey of a woman who appears trapped in an extremely abusive relationship.

In an interview for Women’s Aid Mel B discusses how the juxtaposition of the composed music and the visuals are meaningful, “This project really does represent [what domestic abuse feels like], you’re listening to something so beautiful yet witnessing something so horrendous and that is what you end up living—a double life.”

View this post on Instagram

This is a double life that Mel unfortunately knows first hand. As a survivor of abuse herself, she told ITV News: “I, on stage, yelling girl power, being a Spice Girl, which I absolutely love but, you know behind closed doors it was a very different story. It just goes to show it can happen to anybody.” She’s right, it can happen to anybody, which makes the timing of this short film release even more important.

Mel B’s story is not and should not be treated as an isolated headline—the past year of lockdowns has shown a disturbing rise in domestic abuse cases, not just in Britain but across the world. In the same Women’s Aid interview, Teresa Parker, the Head of Media and Communications for the grassroots organisation further highlighted the point of this campaign by explaining that “there are so many women who are impacted by violence. There are so many women who are raped or go missing. Women are much more likely to die. One woman is killed every four days.” Hearing those words throws us back to those difficult weeks in March 2021, as the tragic case of Sarah Everard brought to light the stories of #AllWomen.

View this post on Instagram

What is the Domestic Abuse Bill?

The timing of this release almost coincides with the UK government’s passing of the new Domestic Abuse Bill. Some of the new changes to the bill, which were announced 2 weeks ago include the addition of controlling or coercive behaviour as a form of abuse as well as non-fatal strangulation, ‘revenge porn’ and many others. Revenge porn is another abusive crime that was brought to the forefront thanks to Love Island star Zara McDermott’s BBC Three documentary, which premiered in February of this year. Although revenge porn laws were first introduced back in 2015, this new 2021 bill makes further promises in following through more heavily on convictions. The crime currently carries up to a two-year sentence.

View this post on Instagram

How has it failed?

As much as the achievements of the bill should be celebrated, it has fallen short of what survivors and activists had originally hoped for. Sadly, it still fails to account for the protection of migrants and those on Universal Credit or other state benefits. Janaya Walker, Legal, Policy and Campaigns Officer at Southall Black Sisters told ITV, “The decision to reject our amendments effectively enshrines a system whereby a woman’s access to support and safety when fleeing violence, is determined by her background and immigration status. We are clear that without equal protection, the Bill is neither landmark nor transformational, it is discriminatory.”

How can we celebrate such a bill that falls short in delivering for all women, especially women of colour? Mel B’s short film comes just after the passing of this new law and sheds light on just how much further we need to go in order to protect all women.

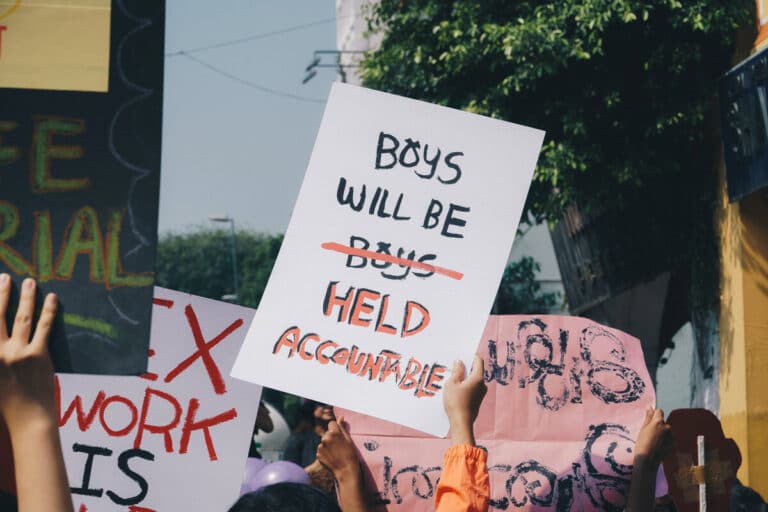

The singer wrote passionately on Instagram that “this is the most important video I have ever made, I will never stop fighting for this cause so please please keep sharing, […] to the abusers we know who you are even though you are still out there thinking you can get away with it. The tide is turning.” Indeed, the tide does appear to be turning, perhaps not through our government’s actions but definitely with the help of influential people like Mel B, the #MeToo movement as well as through the work of grassroots activists. From February to May, 2021 has been filled with incredible highs and terrible lows for women but what has stayed consistent is the conversation. For four months, the subject has remained in the mainstream, as it should, and with Mel B’s stunning new short film, I hope it stays there until the UK government provides the necessary measures for all women.