New report reveals horrifying sexual abuse perpetrated by WHO aid workers in DR Congo

Humanitarian organisations have historically had their fair share of corruption and exploitations in the very countries in which they’re supposed to provide aid. The latest scandal has put the World Health Organization (WHO) in the spotlight for swathes of sexual abuse cases at the hands of its aid workers during the Ebola crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). An investigation carried out by the Thomson Reuters Foundation and The New Humanitarian in 2020 prompted WHO to conduct an independent commission into the allegations made in DRC. The now released report cites accusations from over 50 women.

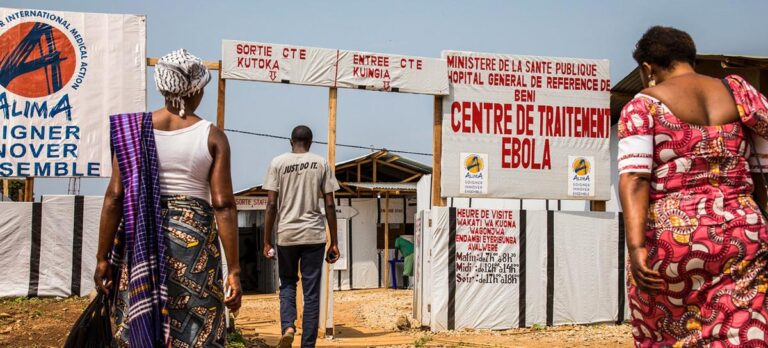

The women in question have accused aid workers who identified themselves as workers from a number of different charities and humanitarian organisations, including WHO, UNICEF, Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières, World Vision, Alima and IOM (the UN’s migration agency) for demanding sex as payment for work conducted throughout 2018 to 2020. The report that was first released yesterday, 28 September, has uncovered one of the largest sexual crimes that United Nations (UN) bodies have been linked to in many years.

A total number of 83 aid workers—21 of whom being WHO staff members—were accused of this sexual abuse and exploitation of women and girls during the Ebola outbreak in the country; nine of these (over 50) accusations alleged rape at the hands of both Congolese nationals and foreign workers. The details of the findings are incredibly disturbing, with local women citing that they experienced being “ambushed” in hospitals and plied with alcohol. According to commission member Malick Coulibaly, many of the accused male abusers did not wear condoms which resulted in 29 of the women falling pregnant, 22 of which were carried to term, and some being pushed to have abortions.

The report cites an accusation made against a doctor from WHO, as well as two other agency officials, for allegedly offering to purchase land for a woman who had fallen pregnant. “The review team has [also] established that the presumed victims were promised jobs in exchange for sexual relations or in order to keep their jobs,” Coulibaly continued in a press briefing. A 14-year-old girl, given the name ‘Jolianne’, disclosed to the commission that in April 2019, she was approached by a driver for WHO and offered to be driven home; instead she was taken to a hotel where she was subsequently raped and later, gave birth to his child.

The report showcases how the male perpetrators working for such organisations like WHO utilised the Ebola crisis and financial burden of such women and girls to exploit them with promises for jobs or to keep their jobs in exchange for sex. The commission is said to have blamed WHO for its negligence in screening the workers it deployed to aid in the Ebola crisis and argues that this is simply one example of structural issues in the organisation’s sexual abuse investigations.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO’s Director General, stated in a press conference that “this is a dark day for WHO.” He then pledged a reform of the organisation’s current policies on sexual abuse, “I’m sorry for what was done to you by people who are employed by WHO to serve and protect you … It is my top priority that the perpetrators are not excused, but held to account.” Passy Mulabama, executive director and founder of the Action and Development Initiative for the Protection of Women and Children in the DRC (AIDPROFEN), told Al Jazeera, “The DRC has been affected by conflicts for so many years … and it’s just unacceptable that humanitarians can still be responsible for sexual assault and sexual exploitation of women and children.”

Julie Londo, a member of the Congolese Union of Media Women (UCOFEM), praised WHO’s pledge to punish accused staff but also stated that the public health body needs to go further, “WHO must also think about reparation[s] for the women who were traumatised by the rapes and the dozens of children who were born with unwanted pregnancies as a result of the rapes.”

“There are a dozen girls in Butembo and Beni who had children with doctors during the Ebola epidemic, but today others are sent back by their families because they had children with foreigners … We will continue our fight to end these abuses.”