Windrush Day 2022: Meet the generations who believe nationality is not defined by racial appearance

Today is the fourth national Windrush Day, commemorating the arrival of the eponymous HMT Empire Windrush (originally MV Monte Rosa) on the docks of Tilbury 74 years ago. 1,027 passengers stepped on British soil for the first time, arriving in what was commonly held as the ‘Motherland’ to help rebuild the post-war nation. 80 per cent of these voyagers were from the Caribbean—along with other countries of the British Commonwealth, including Pakistan and Australia. Over the next 23 years, nearly half a million people emigrated from the Commonwealth and replenished Britain’s National Health Service (NHS), public transport sector as well as the oil and steel industry.

Today, as we commemorate this generation and their descendants, there remains an erroneous assumption that Britain’s Caribbean people are Jamaican and of African descent. In fact, many proud West Indians are of global heritage, with roots in China, India and Europe and their nationality is not defined by their racial appearance.

81-year-old Sister Monica Tywang knows this only too well, having left Trinidad for London in 1952. “When I came to London in 1952 ahead of the Queen’s coronation, people didn’t expect someone who looked like me to be from Trinidad,” she told SCREENSHOT.

Born in Belmont in 1941 as the sixth of 11 children, Sister Tywang’s father was the descendent of indentured Chinese labourers while her mother was of native Carib stock. She became a veteran of the Notting Hill Carnival, one of the most vivid expressions of Caribbean culture in the UK, which she describes is all about liberation and bringing people together.

As Sister Tywang explained in an accent rich with the rhotic tones of Trini rhythms, while she considers herself British and Trinidadian, she still faces questions about her nationality.

“I remember being asked, ‘What part of Jamaica is Trinidad in?’.”

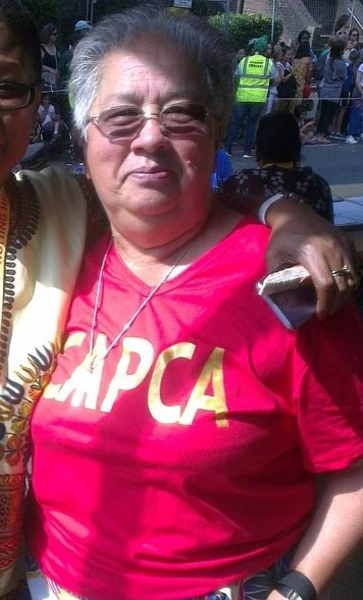

55-year-old singer and producer Joan Achong has also witnessed surprising reactions upon telling people she is Caribbean, as “people assume that most individuals from the Caribbean are Jamaicans.”

Born in Trinidad of Carib, Chinese, Black, Spanish and Portuguese heritage, Achong travelled to the UK in 1990 and went on to launch her own production company. Her musical career was influenced by the Calypso, Soca, RnB, Soul and Gospel tunes she grew up surrounded by. Rightly proud of her heritage, Achong feels there are still many inequalities faced by those of the Windrush generation and their descendants.

“The greatest challenges faced by the Windrush generation are the cultural clash, lack of respect and autonomy, and lack of shared information,” she said. “Despite some of these people having beaten the odds, they are not celebrated among their peers and white counterparts—they remain under-paid, under-valued and invisible in plain sight.”

One of the testaments to the Windrush generation’s struggle for autonomy and recognition is occasional divisions within the diaspora. Council worker Chyrell Williams explained, “Some people can be fiercely protective of their culture and traditions, which of course I respect, but there can be a lack of awareness within our own community that Caribbean people come from all backgrounds.”

Born in South London, both of Williams’ parents are Jamaicans of Indian ancestry, the descendants of indentured workers who moved to the UK back in the 1960s. Though the 44-year-old grew up in a household where Patois was used and Jamaican cuisine such as ackee and saltfish or peas and rice were incorporated, she mentioned that her background wasn’t really talked about while she was a child.

“I think it was too difficult for them to discuss what it was like when they first came here, there was a lot of trauma,” Williams said. “It wasn’t until I first visited Jamaica in my early twenties that I became fascinated by my background and my history.”

Now as a mother herself, Williams explained that finding out the trajectory of her family’s migration to Jamaica is challenging because, as indentured labourers, her ancestors’ names were changed. The lack of awareness around the indentured community’s experience is something Williams is passionate about challenging and often highlights in her Instagram profile with #dontcallmecoolie.

When asked what she considers as her nationality, Williams added, “I consider myself Jamaican. I was born here and love the UK, but I feel like people don’t accept me. People still say ‘You look Indian’ and I’ve even been told that I shouldn’t ‘talk black.’ But my parents are Jamaican, I was raised that way through the way we talk, what we eat and the old reggae they listened to. Jamaican is not an ethnicity, it’s all there in our motto, which is ‘Out of the many, one people’.”

This is echoed by 31-year-old teacher Sara Jamah, whose parents moved from Jamaica to Birmingham in the early 1970s. While her parents are of Syrian and Portuguese descent, Jamah said their Jamaican heritage was a central part of her childhood.

“My parents were both born in Jamaica, their parents were Syrian Jewish and part of the longstanding Jamaican Jewish community,” Jamah explained. “It’s an interesting dual-culture. I grew up speaking odd bits of Yiddish and Patois slang. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve researched our history and feel a strong connection to my Jamaican heritage.”

The cosmopolitan nature of the Caribbean means there are many active religions practiced from Buddhism to Islam. Sham Mahabir, owner of Limin’ Beach Club said, “I’m Indian Trinidadian and was raised Hindu so that shows itself a lot in the food and music of Trinidad. We’re just two small islands but we have influences from every continent as everyone seemed to find their happy place in the twin islands.”

46-year-old Mahabir was born in Sangre Grande and admitted that he loves sharing his culture, food and music with new people, as his Hindu traditions combine with his Caribbean mentality. “There are so many ethnicities in the Caribbean but I didn’t feel any conflict growing up. It was just a mix of people, I was aware there was a difference, but it wasn’t divisive. We had a rich childhood.”

Out of the 13 countries in the Caribbean, most have been part of the Windrush migration to the UK, bringing with them their own culture and traditions. They also ushered diversity in its truest form, a variety of distinct influences and outlooks which combine to make the Britain we know today.

As Sister Tywang mentioned, “Great Britain was the motherland, so I have always been British, but I am also Chinese and proudly Trinidadian. There is no contradiction in that.”