What’s the happiest country in the world? Spoiler: it didn’t win fairly

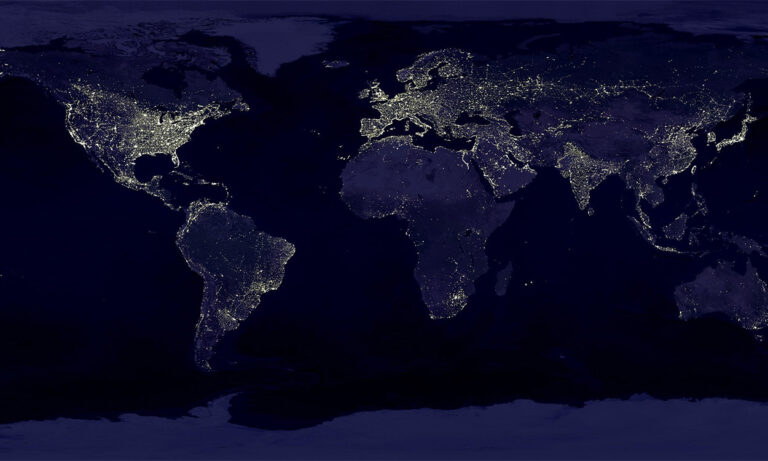

Each year, the World Happiness Report unveils the residents of the happiest countries globally. Countries that usually dominate the top ranks include Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Israel, and the Netherlands. However, these rankings, based on Gallup surveys asking individuals to rate their lives on a scale of zero to 10, have recently sparked criticism for their biases and exclusions. Critics have argued that the report exhibits a Western inclination, focusing on economically prosperous nations while overlooking the historical contexts of colonial exploitation.

Defining happiness

Every year, a United Nations-backed organisation releases the World Happiness Report, ranking countries based on residents’ self-assessments of their life satisfaction. These self-reported assessments are combined with various other factors to create the annual rankings. However, the report’s methodology and focus on life satisfaction have raised questions about its accuracy and relevance.

Happy but yet depressed?

While the report crowns European nations as the world’s happiest countries, it’s a head-scratcher to see some of them leading in both joy and the quest for serotonin. Finland, for instance, wears the “Happiest Country” crown while keeping its pharmaceutical industry quite busy.

@drkaurtherapy 2 million people have been on anti depressants for 5 years or more in the uk. Thats shocking and too high! As a therapist I believe the first step to better mental health is developing self awareness of what you are experiencing- start with learning about what you are going through and focus on making small changes to start to feel more empowered. Mental health exists on a spectrum and some days will be better than others but self awareness means taking time to start to reallt reflect in a much more objective way about yourself so that you can see the dips and learn from rather than get caught up in a cycle of self criticism. #mentalhealthmatters #antidepressants #uknes #ukmentalhealthservices #psychologistoftiktok

♬ original sound - Dr Gurpreet @drkaurtherapy

View this post on Instagram

Another observation was that countries with prosperous economies obviously tend to rank higher as the happiest countries in the world. But they also solely focus on a nation’s overall economic performance and do not account for income inequality. In the US for instance, based on data from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 2022, there are approximately 582,000 people experiencing homelessness, resulting in a national rate of 18 homeless individuals per population of 10,000. But, in some states, these rates soar much higher, hitting a peak of 44 individuals per 10,000. California, Vermont, and Oregon lead the pack with the highest homelessness rates among all 50 states.

@thestreetsofhollywood There’s gotta be a better solution for this. I couldn’t believe what I saw that day. #Homeless #homelesspeople #homelessness #homelesspeoplematter #takeaction #takeactiontoday #losangeles #losangeleshomelessness #homelessinlosangeles #homelessinamerica

♬ original sound - HollywoodBlvd

Whose happiness matters?

The World Happiness Report’s data collection relies on Gallup surveys, which have limitations. They focus on civilian, non-institutionalised adults, excluding populations in institutions like prisons and nursing homes. Unsafe regions for data collection are also often omitted, possibly impacting marginalised communities’ representation. Moreover, there’s criticism of cultural bias, with the report potentially imposing Western ideals of happiness at the top of our epicentre.

Reimagining happiness

The Happiness Report’s reliance on self-assessments also raises questions about how respondents perceive happiness. Rather than a universally individualistic perspective, happiness might be rooted in interpersonal relationships and social harmony. For instance, “interdependent happiness,” which relates to family and peer relationships, plays a more significant role in determining happiness in certain cultures. Western ideas about happiness for example, often revolve around independence, while Eastern ideas emphasise interdependence.

Happiness at the expense of others

The Happiness Report’s rankings fail to consider how the well-being of one group can be connected to the suffering of another. Some nations in the report have histories of colonial exploitation that contributed to their wealth. Belgium, for instance, extracted immense wealth through its colonisation of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, yet ranks among the happiest nations. Similarly, Israel ranks fourth while Palestine, which has experienced dispossession and military occupation, ranks much lower. This highlights the complex interplay between happiness and historical injustices.

In essence, the World Happiness Report prompts us to question the authenticity and significance of its rankings. Is it a genuine representation of global happiness, or does it predominantly highlight the West’s monopolisation?