AI-generated fake faces are more trustworthy than real people, new study reveals

Can you tell the difference between a human and a machine? Well, recent research has shown that AI-engineered fake faces are more trustworthy to us than real people.

Pulling the wool over our eyes is no easy feat but, over time, fake images of people have become less and less distinguishable from real ones. Researchers at Lancaster University, UK, and the University of California, Berkeley, looked into whether or not fake faces created by machine frameworks could trick people into believing they were real. Sophie J. Nightingale from Lancaster University and Hany Farid at the University of California conducted the new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA (PNAS).

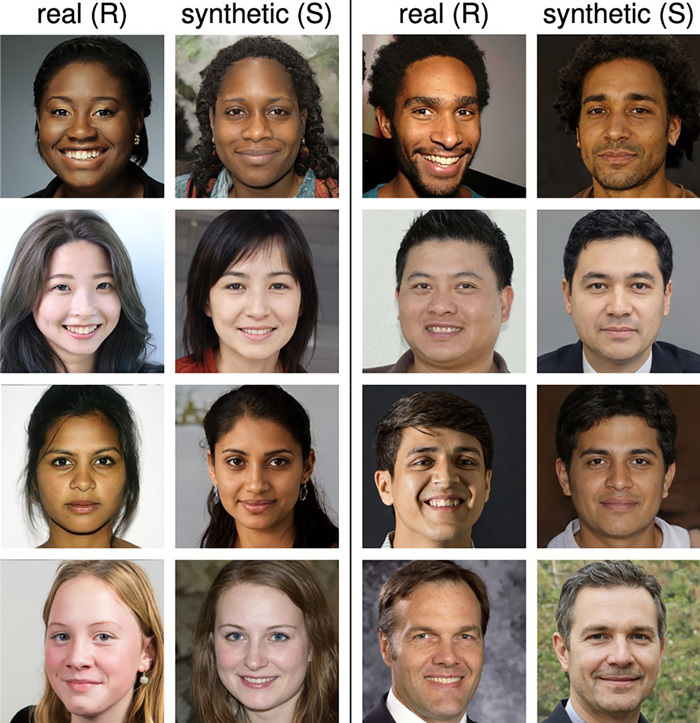

In the paper, AI programs called GANS (generative adversarial networks), produced fake images of people by “pitting two neural networks against each other,” The New Scientist explained. One network, called the ‘generator’, produced a series of synthetic faces—ever-evolving like an essay’s rough draft. Another network, known as a ‘discriminator’, was first trained on real images, after which it graded the generated output by comparing them to its bank of real face data.

Beginning with a few tiny pixels, the generator, with feedback from the discriminator, started to create increasingly realistic images. In fact, they were so realistic that the discriminator itself could no longer tell which ones were fake.

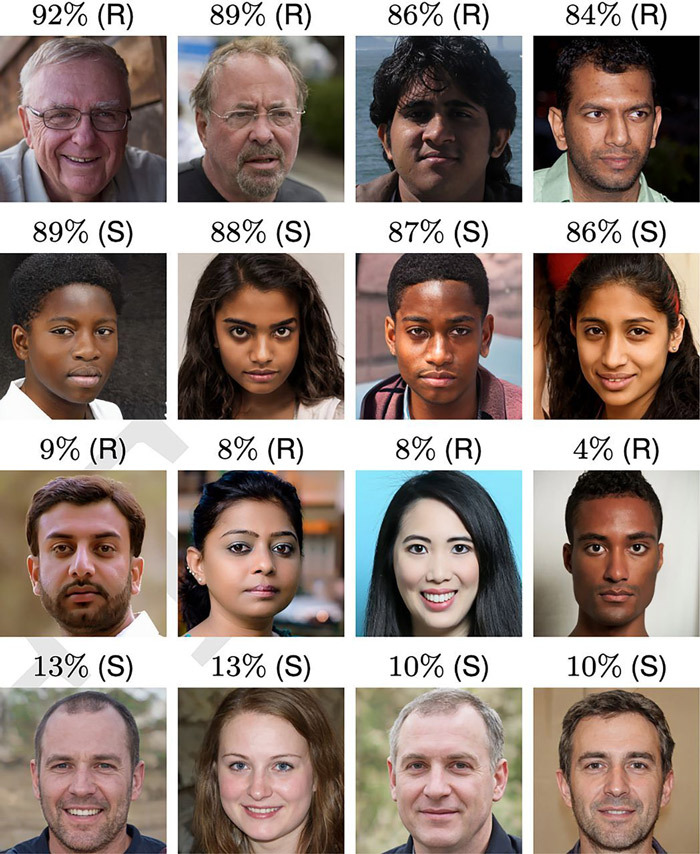

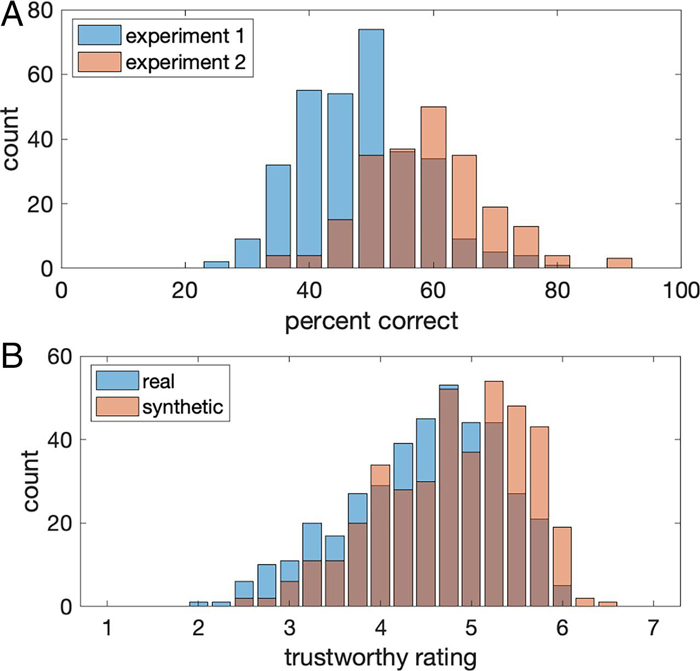

Providing an accurate measure for how much technology has advanced, Nightingale and Farid tested these images on 315 participants. Recruited through a crowdsourcing website, the audience were asked whether or not they could distinguish between 400 fake photos matched to the 400 pictures of real people. The selection of photographs consisted of 100 people from four different ethnic groups: white, black, East Asian and South Asian. As for the result? The test group had a slightly worse-than-chance accuracy rate: around 48.2 per cent.

A second group of 219 participants was also tested. However, this group received training in order to recognise the computer-generated faces. Here, the participants scored a higher accuracy rating of 59 per cent, but according to New Scientist, this difference was “negligible” and nullified in the eyes of Nightingale.

The study found that it was harder for participants to differentiate real from computer-generated faces when the people featured were white. One reason posed for this is due to the synthesis software being trained disproportionately on creating white faces more than any other ethnic groups.

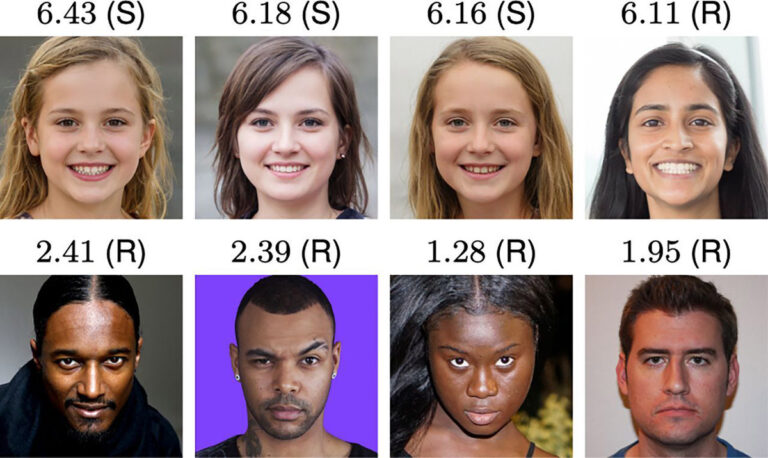

The most interesting part of this study comes from tests conducted on a separate group of 223 participants who were asked to rate the trustworthiness of a mix of 128 real and fake photographs. On a scale ranging from one (very untrustworthy) to seven (very trustworthy), participants rated the fake faces as eight per cent more trustworthy, on average, than the pictures of real people. A marginal difference, but a difference nonetheless.

Taking a step back to look at the extreme ends of the results, the four faces that were rated the most untrustworthy were all real, whereas three that were top rated on the trustworthiness scale were fake.

The results of these experiments have prompted researchers to call for safeguards to prevent the circulation of deepfakes online. Not sure what a deepfake is? Well, according to The Guardian, the online epidemic is “the 21st century’s answer to Photoshopping.” The outlet then goes on to describe how they use a form of artificial intelligence called deep learning to make images of fake events. Hence the name.

Ditching their “uncanny valley” telltale sign, deepfakes have evolved to become ”increasingly convincing,” as stated in Scientific American. They have been involved with a series of online crimes including fraud, mistaken identity, the spreading of propaganda and cyber defamation, as well as sexual crimes like revenge porn. This is even more troubling with the knowledge that AI-generated images of people can easily be obtained online by scammers who can then use them to create fake social media profiles. Take the Deepfake Detection Challenge of 2020 for example.

“Anyone can create synthetic content without specialized knowledge of Photoshop or CGI,” said Nightingale, who went on to share her thoughts on the options we can consider in order to limit risks when it comes to such technology. Attempting countermeasures against deepfakes has become a Whack-A-Mole situation or cyber “arms race.” Some possibilities for developers include adding watermarks on pictures and using the flagging process when fake ones pop up. However, Nightingale acknowledged how these measures barely make the cut. “In my opinion, this is bad enough. It’s just going to get worse if we don’t do something to stop it.”

“We should be concerned because these synthetic faces are incredibly effective for nefarious purposes, for things like revenge porn or fraud, for example,” Nightingale summed up.