How the new dating app Birdy might revolutionise the way we date

Using dating apps has now become a common part of our dating lives. Most people have used or are still using Tinder, Bumble, Feeld, and the many other ones. And yet, many remain single without wanting to be. We complain about the apps’ features, the way they work, and the people we end up meeting on them. We’re accustomed to matching with the way people look instead of matching with their personality, and maybe that’s the primary reason we can’t seem to find ‘the one’.

That’s exactly what the new dating app Birdy wants to change. Birdy is a personality matching app that understands you first, and then finds your perfect match. How does it do so? By asking new users to fill out an in-depth personality test. This idea might sound quite old-school to some, reminding us of what matchmakers used to do before dating apps became the norm. But Birdy’s concept is, as its website states, based on a 92-year-old theory that is trusted by 89 per cent of the Fortune 100, so why not give it a try?

Look back on your previous relationships—the way you and your partner were behaving with each other, what went wrong in the relationship and whether you had plenty of misunderstandings. Most people end a relationship because of these reasons. Relationships can be filled with misunderstandings, hurt feelings and suppressed emotions, which is why, at some point, we decide to go our own way. My aim is not to categorise all relationships by simply saying that they never work out or that they only end badly because of misunderstandings, but it is clear that most people’s previous relationships ended because of personality differences.

Birdy’s main concept relies on the simple fact that in order to have a healthy and lasting relationship, we first need to get to know ourselves. And how can we achieve that? By taking the app’s personality test, apparently. The theory behind the test is based on Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung’s own personality classification. 92 years ago, after analysing data about people’s different personalities, Jung came up with 16 different types of personality and their communication preferences.

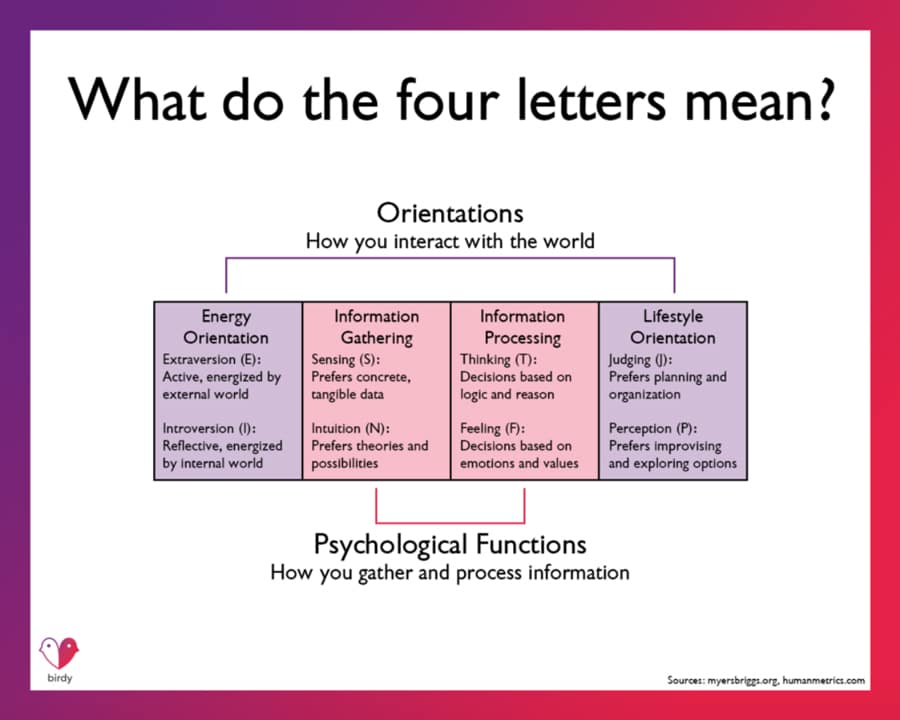

Referring to the Jungian typology theory, Birdy’s website explains that it “categorizes people’s preferences based on how they interact with the world and how they gather and process information to make decisions.” Most people are familiar with the most common application of that theory, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), but Birdy “goes the extra mile and puts a romantic spin on it.”

The whole concept might sound too complicated to truly work, but the end goal is actually quite simple: to help you fall in love, as cheesy as it sounds. Filling out the test takes more time than your usual Buzzfeed quiz, but the 39 questions do the job. In-depth questions push people filling it out to put themselves back into the mindset they had when they were younger, before they started forming a ‘social self’.

Screen Shot spoke to Juliette Swann, the founder of Birdy, about where the idea came from and what’s next for the app. After spending 5 years in a relationship with someone who she felt never understood her, Swann had a horse accident and broke her spine. It gave her perspective and made her realise “that I was wasting my time with the wrong person and that I needed to start focusing on my own life and what I desired.” That’s why, when Swann founded Birdy, she wanted the app to “go back to the basics, to the things that our parents may not have taught us: first love yourself because people love you for who you are.” That’s where the personality test helps you find out who you are.

The test informs you on which type of bird you are—what personality type you are—in a detailed analysis. On top of that, it also gives you an elaborate profile of your perfect match. What results did I get? ISFJ, aka the weaver bird, aka the introvert that aims to please everyone. Is this description accurate? To a certain extent, yes. The test also revealed my perfect match’s personality, ESFP, aka the budgie. Same here, the personality description of the budgie sounded like every person I dated. Then again, just like with astrology, people always find something to relate to, but the fact that this test is based on Jung’s psychology gives it just a tiny bit more weight than astrology and tarot reading, at least in my mind.

Swann is aware of that, and she is already talking about ways to improve the accuracy of Birdy’s test, “Personality tests are subjective and it’s hard to set every user in the right mood to answer the questions the right way. We will put in place a system of verification. Every time the user makes a verification process, he increases his ‘type certainty percentage’.” The app will also soon feature more filters to ‘classify’ its users.

Birdy might find your perfect match or it might not, but what seems obvious is that it has a strong potential to change the way dating apps push us to look at relationships, as well as changing the dating experience in general. We’re almost in 2020—it is time we date people for their personality, not only for their looks. So if you feel like you’re in the mood for a new approach to dating and want to test the alpha version of Birdy that will be available on 5 January, you can register on the waiting list and will receive your code to access it. Good luck.