Opinion

Why does everything look the same right now?

By Will Stokes

Opinion

Why does everything look the same right now?

By Will Stokes

Updated May 19, 2020 at 03:24 PM

Reading time: 3 minutes

Trends

May 1, 2019

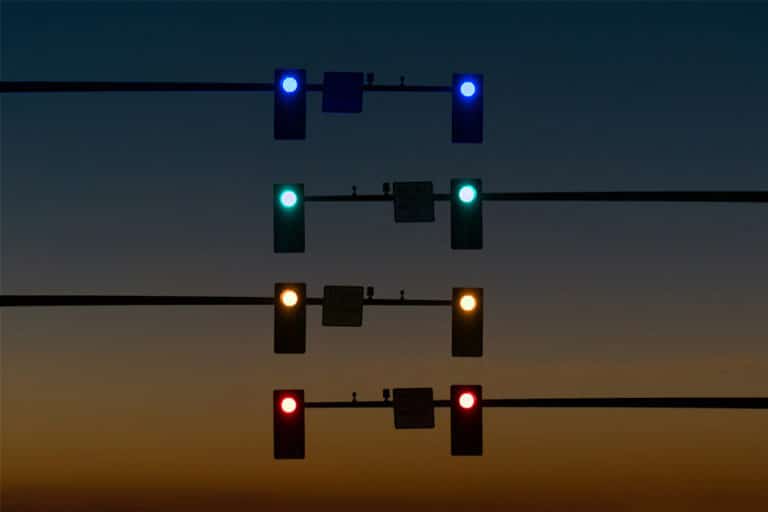

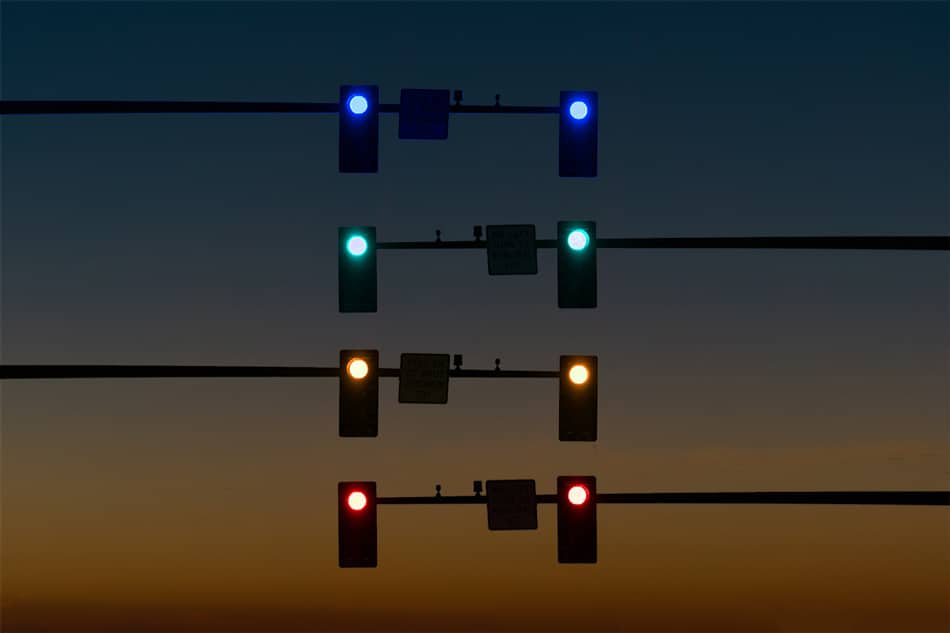

All around the world, things are looking more and more the same. Coffee shops, Airbnb listings, and boutique hotels feature the same subway tiles, brass fixtures, and neo-Scandinavian minimalist furniture, regardless of what continent you’re on. A few years ago, Kyle Chayka in The Verge coined the term ‘AirSpace’ to describe the eerie sense of visual sameness invading built environments across the world, helped along by Silicon Valley forces like Airbnb and social media feeds. A few years on, the AirSpace phenomenon still exists, but it is slowly being eclipsed by new singular trends in visual design.

The Atlantic declared in April that the “Instagram aesthetic is over”—noting the recent trend towards messy authenticity, DIY photography aesthetics, flash photos, longer captions, and double- (or triple-) posting. People grew tired of hyper-staged photos, saturated colours, and the culture reached its aesthetic tipping point. But even these more ‘authentic’ trends, many of which were generated grassroots-style by Gen X digital natives, are already being co-opted and expanded on social media by major brands like Balenciaga, Off-White, or Vetements.

The AirSpace phenomenon was undeniably real. But a few years later, it’s obvious that it was not permanent. So why does everything still look the same, even if it’s a different flavour of ‘same’ than it was in 2016? The simplistic answer is that design is a pendulum, and humans are drawn to trends. But a closer look at the platforms that enable today’s culture industry underlines how technology is restricting our choices to an ever-smaller set of ‘accepted’ visual styles.

Visual design trends in the world of branding and lifestyle startups are following a similar trajectory. Successful companies in the early and middle 2010s ushered in a conservative mix of sans-serif fonts, pastel backgrounds, still-life stock photos, and hand-drawn icons. In an age of globalisation and complexity, consumers craved simplicity, and minimalist design became a product that was as important as the actual products and services sold by these companies.

Apple followed the trend by eliminating skeuomorphism from iOS, trading in ‘kitschy’ textures and gradients that approximated real-world materials for a flat, monochrome standard. Soon, every new digital brand or company was copying these aesthetics. When a startup could utilise a stock image platform like Unsplash and a minimal template from Squarespace to design their homepage, for example, what would justify the cost of hiring an actual photographer or web designer to create original content? Once again, an aesthetic singularity was reached, and consumers demanded something else.

The redesign of the Chobani yoghurt brand in 2017 signalled a cultural pivot towards a new visual maximalism. Gone were the angular sans-serif capital letters of the Chobani logo, replaced in favour of a vaguely 70s chunky serif, with a mood board featuring colours like ‘milk chocolate,’ ‘geranium,’ ‘rose apple,’ and ‘natural’. The ecstatic online reaction to the rebrand of a yoghurt company would have been impossible to predict—but consumers had grown tired of cold International-style minimalism, and the visual warmth conveyed from the rebrand was a timely reprieve after the uncertain year of Trump and Brexit. Other brands also introduced expansive colour palettes, maximalist designs, and serif fonts in their logos—like the Dropbox and Medium redesigns of 2017, and the new masthead for The Guardian, introduced in 2018.

Instagram, arguably the primary outlet for creative content on the internet today, has grown from its launch in 2010 to a platform of 1 billion monthly active users in 2018. This network effect continually reinforces its primacy—the social network with the most users, in turn, becomes the most valuable, and generates even more users by already being the largest network. But while this vast expansion has connected a billion people to a global creative network, this increase in access does not correlate to an increase in aesthetic diversity or heterogeneity. Much like the law of network effects makes the largest social media network also the most valuable, the algorithms that govern how content appears on a news feed or on a discovery page prioritise the most successful content over all else. And in a world where even social media is a market economy where everyone competes for likes, individual users must imitate established visual trends in order to expand their reach through the algorithms.

New ventures, whether they be aesthetic, artistic, or commercial, must be primarily concerned with economic viability from the outset in this age of ruthless late capitalism. Because they must be focused on economic viability, they therefore adopt the values and aesthetics of the most successful previous ventures. Take a look at some of the most aesthetically ‘innovative’ companies of the last several years, like Warby Parker and Allbirds. These are not particularly innovative companies. These firms took established market ideas like vertical integration, direct-to-consumer sales, and minimalist design, and applied them to new lines of business. Their visual aesthetics appeared to be unique to the industry when they launched, but now they are lost in a sea of design sameness imitated by firms across many industries. But when this visual sameness means better sales, it means the company has a better chance of surviving. And thus we return to the primary catalyst of our cycles of aesthetic sameness and trend changes—the primacy of the profit motive, and the welding together of aesthetic taste and the need to make money with as little investment as possible.

Capitalism promised us an explosion of individual choice, but it has only given us a series of aesthetic singularities, fused to the primacy of the profit motive and irrespective of true creative expression. How can we break the cycle? We can start by reducing the power of dominant social media networks to shape our aesthetic taste and creative production—through creating digital design explicitly designed not for social media, and by re-investing in non-digital mediums. Physical zines and art, even experimental websites, can be methods of creative expression that are radically detached from social media, and these mediums have the potential to facilitate bespoke visual aesthetics that cannot be whitewashed by ad-supported platforms and discovery algorithms.

Next time the urge to create something hits us, we should consider putting down our apps, and picking up a pencil instead.