The British Army’s marketing needs a 2019 wake-up call

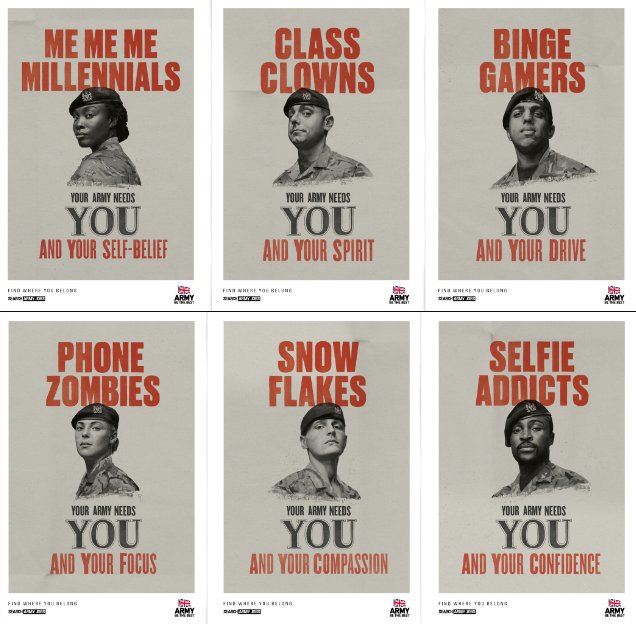

Call me old-fashioned but rarely do you get someone to do something you want by insulting them. “Snowflakes”, “Binge Gamers” and “Me Me Me Millennials” were just some of the few terms used by the British army in an attempt to recruit 16-25-year-olds via updated iconic WWI army posters. Living in a digital world, of course, Twitter went up in flames about this. Some argued that millennials, in fact, were acting like snowflakes over a few words—it’s just an ad, right? Saying one is a “binge gamer” is surely just another way to show the stamina and dedication a gamer staying up all night has.

Yet this comeback fails to see how deep the problem with language is when it concerns the army and ignores the influence and power Britain’s international and political interests have socially across the world. Regardless of its flailing Brexit pound, Britain is still seen as aspirational for many, especially in previously colonised countries across the world, therefore its culture is also one to look up to. So what are we saying about new voters and young adults by essentially calling them to arms by telling them off for being selfish?

This idea of millennials being narcissistic does not just sound old fashioned but is, and in the same outdated breath, social media tends to always be blamed for the foundations of these arguments. The army is essentially saying young people are too busy taking selfies (one of the posters even uses the words “selfie addict”) to care about their country—while ironically sharing their campaign across the same social channels.

What it neglects to see is how much young people are doing more than ever because of this tool. “Creative” was amongst some of the most published terms millennials used to describe themselves while Google searches for how to be an activist skyrocketed in 2018. Whether that was heading to a feminist march that helped girls who are among the poverty line access free sanitary towels at school (just like Free Periods organised with 2,000 other protestors i.e. young people showing up for their peers), or is the push for the Gender Recognition Act for transgender rights in October 2018. I could go on and on but I won’t because you’ve already witnessed it. And probably retweeted it too.

Yet this poster has worked—hasn’t it got everyone talking about it? In an ultra Piers-Morgan-Katie-Hopkins-style bash, its hypocrisy has also gone viral. The tweet “Which 47 year old man came up with these” aptly said what everyone else, sorry, 16-25-year-olds largely thought of in the room. This disconnect with young people is not just shown in how we’re slandered as good-for-nothings but also the toxic language used in the campaign reveals a whole lot about British Army’s relationship with matters of mental health.

The wimpish qualities of a ‘snowflake’ undermine mental health issues such as anxiety and depression—issues millennials are more succumbed to due to the global market competition, lack of jobs and decrease in quality of life while general costs are on the rise. The defence secretary, Gavin Williamson, however, has defended the campaign, calling it “a powerful call to action that appeals to those seeking to make a difference as part of an innovative and inclusive team. It shows that time spent in the army equips people with skills for life and provides comradeship, adventure and opportunity like no other job does. Now all jobs in the army are open to men and women. The best just got better.”

But something isn’t working. The campaign was a direct result of not meeting recruitment targets—something Capita, an outsourcing giant, have been given £495m to do. 47 per cent of applicants have dropped out of the process voluntarily in 2017-2018 while the army has only 77,000 full trained troops instead of the 82,500 target. The British Army and Capita argue it’s due to the length of training that applicants have fallen through but could it also be a result of the British Amry’s archaic ways of doing things and its inability to speak to those they have so brazenly tagged ‘snowflakes’?

Language and ideas have a trickle effect. What this campaign shows, beyond yet another boardroom of decision-makers who are completely disconnected from the public they are targeting, as the toxic culture towards mental health within the country that is still raging. So if the British Army thought it could lure a generation by textbook negging them and pasting diverse faces on its posters, it needs to catch up and realise we don’t do that in 2019.