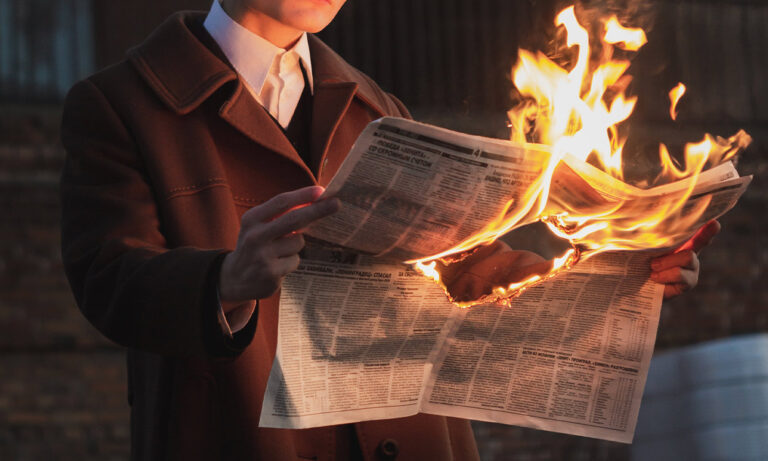

How the mainstream media’s reframing of the truth is causing an erosion of human empathy

In 2023, just like 2022, the truth is liquid—taking the shape of whichever container it’s dispensed into. This harsh reality has resulted in the partial (and sometimes complete) vanishing of truth. Facts fall by the wayside, replaced by single-minded narrative stories which almost always peddle a particular agenda, be it political or social. When it comes to reporting, clickbait headlines are not written to only appeal to the masses, but they are also meticulously designed to impose and reinforce an all too often narrow mindset.

Depending on who the subject—or the object—of the story is, the shape of the container changes. We are fed a variety of different stories, each of which further damages and skews the ways in which we relate to the outside world. By recognising the behavioural and psychological techniques that are at play here, we can begin to demystify the design of these truth-moulding mindsets.

Why has police brutality against black people in the US been reported as actions of “a few bad apples” in the workforce? Why did the Netflix docuseries Harry & Meghan solely focus on tabloids when the real cause of their suffering lies elsewhere?

How framing feeds us problematic views without our knowledge

The most significant theme linking these stories is their use of the behavioural technique of “framing,” which allows for an underlying mindset to be concealed beneath the surface of the text—dangerous rhetoric and language hide in plain sight because of this.

It’s human nature to struggle with absorbing the truth as is. Speaking to SCREENSHOT, Akan Abdula, co-founder of the FutureBright Group—which consists of research and strategic consultancy agencies—explained: “We are not wired to assign value to a given subject without any reference point.” For example, in order to say that SOS is SZA’s best album, we would first have to listen to her previous albums to provide a reference point.

“One of the key principles of behavioural economics,” Abdula further pointed out, “is that there is no absolute value—we can only appoint value to a certain thing through comparison.”

What Abdula means by this, is that without firm and consistent points of reference, we struggle to understand things and that comparison of ideas is what keeps them valuable. There isn’t an inherent value to any one statement without the points of reference as backup.

This need for comparison makes room for, as Abdula pointed out, “our ability to change the perception of the truth by simply changing what we compare it with.” Just look at how the Western news channels half-heartedly referred to Ukraine as “not Iraq or Afghanistan” while reporting the war, leading to a comparison of Ukrainian lives to Middle-Eastern lives. These statements inherently assigned more value to the former, as if white lives have any more value to them than those lost in the Middle East.

This way of framing the truth camouflages another message in itself, signifying a certain mindset. “What you say is less important than how you frame it,” Abdula summarised. Within the context of reporting, he highlighted that “it is about ethics, and we can say that the news channels right now are mostly using framing in an unethical way.”

How framing leads us to dehumanise others

The main result of unethical framing is mass “empathy erosion”—a term coined by British clinical psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen. In his book Zero Degrees of Empathy, he replaced the unscientific term “evil” with “empathy erosion” to refer to when we start regarding a person as an object rather than a human being, in turn making us capable of hurting them.

Baron-Cohen pointed out that people are not motivated to do cruel things for cruelty’s sake. It isn’t a momentary blip for a policeman to take an unarmed black person’s life. It isn’t normal for Middle-Eastern people to die because that region of the world is perceived to be the home of terrorism.

Human cruelty does not exist solely because some parts of the world, or some people, are inherently evil when compared to others. Some people are evil, but no one group is more evil than another. In the context of unethical reporting, empathy erosion happens in two stages: dehumanising the subject and distracting the public while doing so.

What news channels lose sight of, in their effort to bring the truth while reframing, is firstly the humanity of their subjects. When we regard the outside world from a single-minded point of view, “we relate only to things, or to people as if they were merely things,” Baron-Cohen wrote. Our truth is the only valid one, and because of this, we reject any value that might lie beyond our own personal experiences. Ignoring a human being’s subjectivity and feelings is surely one of the worst things we can do to another person, and yet we see examples of it every day in the mainstream media.

Amid a slew of racist and misogynistic examples discussed during Netflix’s Harry & Meghan docuseries, one incident particularly exemplifies the topic of framing. During the dehumanisation of Markle, Danny Baker—former BBC presenter—posted a horrifically discriminatory tweet following the birth of Prince Archie featuring a couple holding hands with a chimp.

The framing here is clearly a manifestation of a certain mindset, one that reflects hatred for someone simply because they’re black and a woman. In addition, misogynoir is not the only dehumanisation this single-minded narrative exercises.

While reporting the bombing that took place in Taksim Square, Istanbul on 13 November 2022, the New York Times International announced the news with a caption that read, “Of the tens of millions of tourists who visit Turkey each year, many spend time in the area where Sunday’s bombing took place.” While reframing Turkey as only a holiday destination, this narrative fails to acknowledge the existence of ‘other’ human beings who actually live there, and whose lives matter, too. As we lose any ability to relate to an ‘other’ as human, and get stuck in our single-minded vision, our perception is “by definition unempathetic,” as Baron-Cohen explained.

Of the tens of millions of tourists from around the world who visit Turkey each year, many spend time in the area where Sunday’s bombing took place. https://t.co/iyV2duE75S

— New York Times World (@nytimesworld) November 13, 2022

These examples of unethical and unempathetic framing create a pollutant ideal that normalises cruelty for human beings who are perceived as ‘others’ by these singular commentators. Empathy is not only our ability to identify other humans’ feelings or thoughts, but it is often our most valuable tool for understanding, and one this reporting style so often lacks. A human response is much needed in today’s cold and increasingly insular outlook.

How framing takes away from the ones who should be held accountable

Reframing not only damages mass empathy, it distracts the public from the power that authorities have to create change. The aforementioned docuseries, which has its own framing baggage too, focuses mainly on tabloid newspapers as the driver of the couple’s decision to exit the royal family.

This focus fails to offer any further disclosure regarding Markle’s own claims in her Oprah Winfrey interview that an “unnamed member of the royal family had commented on how ‘dark’ their baby’s skin would be.” However, the criticism is against their own royal institution, one that told them “there’s nothing we can do to protect you.” Could it be more about systematic discrimination than the paparazzi?

Another notable instance of framing is the means by which outlets distract the public from those who should be held accountable, through the highly dangerous and untrue narrative of “bad apples”—a narrative often found in the reporting on police brutality against black people in the US.

On one hand, National Security Adviser Robert C. O’Brien attempted to reassure the public with the words, “We have got great law enforcement officers—not the few bad apples, like the officer [Derek Chauvin] that killed George Floyd. We got a few bad apples that have given law enforcement a bad name.” On the other hand, unarmed black people are more than three times as likely to be shot by police as unarmed whites. Bad apples come so often from rotten trees—a reflection of structural racism rather than individual cruelty.

This narrative framing can be found in the covering of news about other minorities, too. In the New York Times article that reported the mentioned bombing in Istanbul, the main focus was on how it would affect tourism. The attack that killed at least six people and injured 81 others was framed with callous focus on how it would affect tourism in the city, rather than, oh you know, all the people who lost their lives to a devastating attack.

This single-minded narrative that both dehumanises its subjects and distracts the public from the actual problem fails to hold authorities accountable. It is deeply rooted in a lack of self-awareness, because “someone with poor empathy is often the last person to realise they have poor empathy,” as Baron-Cohen summarised.

When other people’s feelings aren’t on our radar, we are so often oblivious to how we might come across, which leaves us “free to express any thoughts in our minds, without considering the impact.” To put it simply, we feel blindly entitled—and publications do very little to change this unethical framing.

Paul Butler, law professor at Georgetown, former federal prosecutor, and the author of the book Chokehold: Policing Black Men, calls it “torture.” Not in a way that pulls out your fingernails, but a kind of psychological warfare, “which is to make people feel both humiliated and terrified that anything could happen to them at any moment.”

Mass empathy erosion is not just the simple act of supposed scapegoats. It is a widespread process in which a specific mindset is imposed and reinforced, reducing the opacity of any form of ‘other’ in our perception. These very real humans are left with little autonomy to try and build change in a system that repeatedly puts them down through the subtle and nuanced technique of framing.

With the lack of awareness news channels have towards humanity and themselves, blind entitlement is the only communicational currency they exchange. And the reaction it ignites is far deeper than the eye-roll we get from our slightly racist relative. As a woman who happens to be Turkish, I can confidently say that being repeatedly dehumanised settles within the mind, inhabits the body, and weakens the light that shines in our eyes.

For that reason, it’s crucial we start exercising empathy and go beyond that single-mindedness, which is an exercise we all should do, especially when consuming the news. To rediscover that a life is a life, and a death is a death. On top of that, to see that no one was asking our permission to exist in the first place. As trans advocate, actress, author and model Dominique Jackson put beautifully in her acceptance speech for HRC National Equality Award, “We’re all human beings. I will never ask any of you for respect, I will demand it.”