The day my brain broke: My OCD journey and the future of psychedelic treatments

If you thought obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) was about cleaning, then you need to clean up that image and word association in your mind. OCD left me alone with the worst possible thoughts known to humankind. It led me to lock myself away, convinced that I was a threat to society. But, every cloud has a silver lining. I’m currently part of a NHS trial exploring how psychedelic mushrooms could potentially help my symptoms. Here’s my recovery story from OCD.

What is OCD?

Society still holds a warped perception of what OCD actually is, diminishing and devaluing what sufferers go through on a daily basis.

OCD is a common mental health condition where a person is afflicted with obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours that range in severity. According to the University and College Union, “OCD affects about 1 to 2 per cent of the [UK] population,” meaning it is incredibly common, yet the disorder constantly faces grave silence when it comes to awareness.

I live with sexual orientation OCD (SO-OCD), sometimes also referred to as homosexual OCD, in which I face obsessive ideas about being attracted to the same sex, and harm OCD—thoughts and worries I could harm other people and myself. OCD thoughts are known as “ego-dystonic,” which are beliefs out of alignment with your morals and values.

My OCD story

My OCD story began with a dream where I suddenly believed I was gay. Anxiety caused me to vomit and I couldn’t stop myself from seeking evidence to prove that was the case. I became used to feeling this way every single day for three years.

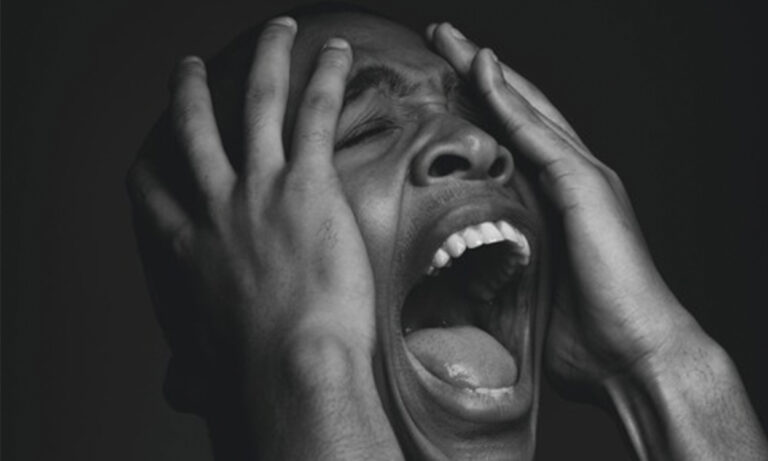

OCD causes breakdowns, with my personal first being a result of thoughts surrounding sexual assault. Initially, I believed I was hearing voices. One day, I panicked and screamed at one of my female friends, telling her to leave because I was so worried I was going to hurt her.

Then suddenly, the thoughts left. I tried to sleep it off, thinking that perhaps all I needed was some rest, only to be hit with images of suicide and blood. I called an ambulance, and they referred me to a mental health team. I decided to undergo psychodynamic therapy—a form of therapy which focuses on the psychological roots of emotional suffering.

Unfortunately, my treatment only sent me further down the rabbit hole as I sought more questions than what I got answers for, in turn making my anxiety shoot through the roof.

The final straw was when I was with my friend and a suicidal vision came into my mind which understandably panicked me to the point that I begged her to leave. An Uber was called straight away and I cried to my loved ones, sharing with them that I felt suicidal and depressed. For the next couple of days, my life shut down and my mind became my worst enemy.

On Saturday 4 June 2022, I found a new therapist—Emma Garrick, otherwise known as the ‘anxiety whisperer’. She saved my life, and to her, I owe the rebuilding of my broken OCD brain. My recovery journey started the following Monday. As you can imagine, it has not been easy, and it would be naive to think that all my worries have been put to bed. But I have since found a purpose in helping others by sharing my story.

The gold standard of therapy for recovery from OCD is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and exposure and response prevention (ERP). Exposure therapy begins with confronting situations that create anxiety without the intention to cause any danger. On these terms, the source of distress should be something that the person can tolerate on a daily basis. An exposure hierarchy is created in order to face and confront higher levels of discomfort. In turn, you’re able to learn ways in which you can avoid giving in to any compulsions—which can develop into avoidance, counting, and not looking at anything.

I also participated in acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which taught me how to pay attention in the present while simultaneously accepting thoughts and feelings without judgement. Paying attention means not allowing anxiety to rule your everyday existence, worrying about the future and predicting negative outcomes or ruminating about the past. ACT essentially aids by helping you progress through difficult emotions and, instead of focusing on the negative, divert your energy into the healing process. A core tenant of the therapy is acceptance, rather than understanding.

Sadly, not many black people or other ethnic minorities speak out about OCD and mental health in general due to the persistence of shame and stigma within cultural norms. This is why I’ve made it my mission to use my social media influence to raise awareness about the condition. I recently appeared on Channel 4’s Unapologetic chat show hosted by Zeze Millz and Yinka Bokinni. But my work here is not yet done.

Psilocybin and the future of OCD treatment

Psilocybin is the psychoactive ingredient found in magic mushrooms which are known for their proposed healing properties. Due to the war on drugs and a perpetual societal stigma attached to drug use, psychedelic substances have long been relegated to the underground space. This covert attitude has, in turn, prevented any and all mainstream medical research from being conducted.

According to a 2006 research project, psilocybin was reported to significantly reduce symptoms in OCD patients. The results were positive, yet, no further research has been carried out since due to a lack of funding.

That being said, it seems like things are about to change, given the new NHS trial for psilocybin with Imperial College London which aims to assess the therapeutic capabilities of psychedelics on OCD symptoms.

I first heard about the trial during my time as a voluntary advocate for Dr Nick Sireau’s organisation, Orchard OCD—a UK-based charity with the sole mission to fund better and faster treatment for those coping with the condition in question—where I helped others and improved research in my own community. The trial is a momentous occasion and could potentially change lives, particularly if the conclusive findings can be made available as an alternative form of treatment for those living with OCD.

Orchard OCD has collaborated with professor David Nutt, Imperial College London, and professor Naomi Fineberg, Queen Elizabeth II hospital, to run the aforementioned pilot psilocybin clinical trial. The study is due to last 18 months, recruiting and following up a total of 15 patients.

Looking to the future, my aim would be to deliver a TEDx Talk in order to stimulate a greater societal conversation in regard to developing new and better treatments. This condition affects over one million people in the UK, yet there is still an overwhelming lack of sufficient funding and research. According to Mental Health Research, a mere 89p is spent on OCD-targeted research each year for every person affected in the country.

Moreover, recovery-focused charity OCD-UK found that, in 2010, the total economic cost of mental illness in the country was a staggering £105.2 billion, of which anxiety disorders including OCD cost £9.8 billion a year.

Recovery from OCD is not linear, neither is it easy, but I promise it is possible. I strongly believe that our generation will continue to revolutionise the way we view and treat mental health. Generations before us existed in a survival mindset, where they sacrificed their mental health to give us the freedoms and greater understanding we now have. With that freedom, we need to dismantle societal norms and destructive behaviours so that we can make the world a better place for us all to cohabit.

OCD may have nearly taken my life and still causes people torment but broken crayons still colour the same—in spite of everything you have been through, you still have purpose and value.