One year later, the selling of an AI painting shows that AI art is still not that groundbreaking

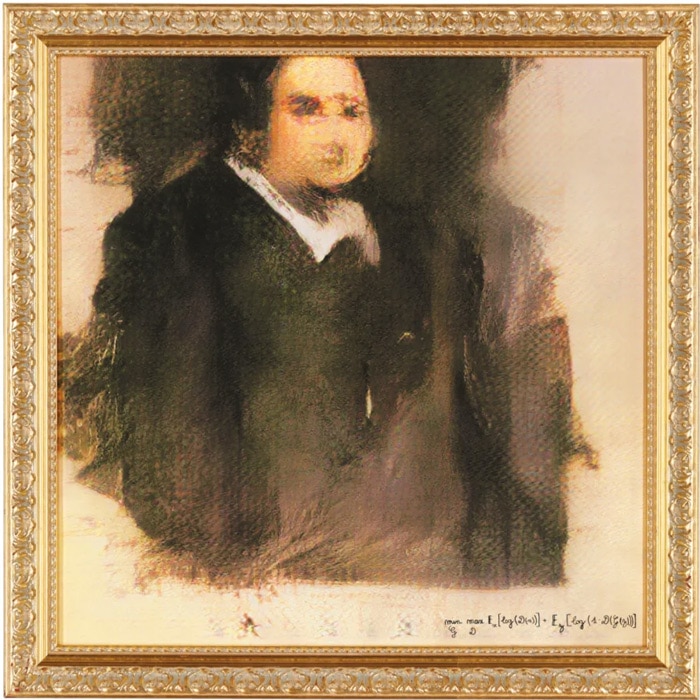

To mark the one-year anniversary sale of the Portrait of Edmond Bellamy, the first AI-generated art piece auctioned at Christie’s in New York for $432,500, I ask myself, can anyone who has some kind of algorithm know-how become the next Andy Warhol? Is art made by machines ‘good art’? Should it even be considered art at all? These questions have been asked around the art and tech circles since last October, when the blurry 19th-century-inspired portrait created entirely by an AI machine was unveiled at the iconic auction house.

What makes AI art groundbreaking is that it uses GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks). This is a machine modelled after the human brain with two approaches to thought and conception: first, it scours images and detects patterns using an algorithm. Then it generates images that align with that algorithm. In a rigid industry ruled by ‘White Cube elitism’, it’s surprising that tech mediums such as artificial intelligence, deep learning, and adversarial networks are having a moment in the art world. Although this historic auction signalled the disruption of art by the digital revolution, its controversy has not been ignored.

Some may argue that this could be the end of art as we know it, with artists worrying about machines possibly stealing their jobs and putting them out of work. Others have debated whether machine-made paintings and prints should even be considered art. Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Jerry Saltz has said “AI artists are striving for their machines to paint like humans do or even better. But why should they?” If artists and scientists are striving to pioneer in this new form of artistry, why not explore other modes of creativity? These are both exciting and scary prospects, but the question people should be asking themselves is why is AI art created only on paintings and prints?

To some, paintings and prints can be considered as an outdated medium, and if AI’s advantage is being more cognitively advanced than humans, why not use it on a more advanced level? One that springs to mind is digital face filters (yes, digital face filters like the ones on Instagram). Hear me out—although their popularity amongst the selfie-obsessed has been pioneering what is digital beauty and disrupting societal beauty standards, they should also be recognised in an art context.

As we are always interacting with flat dimensions, seeing art through a face brings a new perspective to understanding art. Filters such as the ones made by digital artist Johanna Jaskowska, who created the famous Beauty3000, Blast, and Zoufriya, have been transforming faces into otherworldly living artworks. Using AR-made face filters as a medium for AI-generated imagery could catapult the future relationship between art and tech.

Think about it this way—the Mona Lisa is the most photographed art piece in history, yet everyone would kill to have the original sitting in their homes. Who wouldn’t want to buy a face filter if you knew you and only a slim few others would be able to experience it and show it off on your social media platforms? Plus, if AI-made blurry prints can make it into Christie’s, then why can’t face filters? The art world should see beyond the White Cube and realise that art in the digital era shouldn’t just live on canvas anymore.

Why put a wealth of knowledge on an outdated medium? AI art is presenting a new form of creative thinking that is beyond human comprehension, and it’s a disservice to put this contemporary way of thinking into old mediums. Besides, seeing AI used in creation with already overused mediums doesn’t seem that groundbreaking. For being so innovative, using old methods seems counterintuitive.

The reason why some aren’t convinced of the significance of AI art is that it looks like it was badly made, and, more importantly, that a human made it. Shouldn’t we focus on the fact that it was machine-made and conceptualised by a machine? Although seeing face filters on auction at Christie’s or seeing digital artists such as Johanna Jaskowska, Jade Roche, and Mathieu Ernst next to the Old Masters in museums may seem like a stretch for now, who knows where the future of art lies in the techy world. In the words of Andy Warhol himself, “Art is what you can get away with.” We just need to push the boundaries.