For writers, NFTs could be game-changing

Recently, publishers have been trying to get in on the action and a growing number are toying with NFTs in a variety of ways. TIME’s ‘Space Exploration’ cover art NFT sold for over $249,000 and the company is also building a 50-person team exclusively focused on NFTs and crypto. Bleacher Report auctioned NFT basketballs for around $810,000 in collaborations with 2 Chainz, Quavo, Lil Baby, and Jack Harlow. Meanwhile, The New York Times auctioned off a column about NFTs as an NFT and it’s now worth over $720,000.

But NFTs could also prove to be game-changing for writers. Mario Gabriele, who runs the business analysis outlet The Generalist, recently led a project that—to his knowledge—culminated in the first tokenised, crowdfunded equity research report. In simpler terms, The Generalist turned a written report about Coinbase’s IPO (which was accompanied by visualisations from digital artist Jack Butcher of Visualize Value) into a set of NFTs that benefited everyone involved.

Writers and artists got paid through crowdfunded support, supporters were rewarded through returns from a subsequent NFT sale of the work for 28.6 ETH (over $59,000 at the time), and collectors gained ownership over one-of-a-kind NFTs. All in all, it was a win-win situation.

Last night, the $GENERALIST experiment ended. By the numbers:

— Mario Gabriele 🦊💭 (@mariogabriele) April 2, 2021

1. Raised 20 ETH on @viamirror from supporters

2. Shared 10 ETH w @jackbutcher

3. Shared 5 ETH w S-1 Club contributors

4. Released our coverage

5. Minted 3 NFTs

6. Sold 3 NFTs for combined 28.6 ETH

A few thoughts. pic.twitter.com/yE9QDnuePD

In a conversation with The Hustle, Gabriele said he thinks NFTs “could offer newsletter writers an alternative to subscriptions and sponsorships.” But let’s back up a bit. Does that mean that soon enough, even your Screen Shot Pro subscription will be sold as an NFT?

“What gives an asset its value? The founder points to the product, the venture capitalist gestures at a sloping graph, the banker underlines figures on a balance sheet,” writes Gabriele, adding “What about the artist or the writer?”

Throughout history, creative works have been priced according to scarcity—we tend to give value to objects based on their rarity. That’s why, for example, Da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ was valued at $850 million in 2019, while a good replica might be worth a few thousand, and a high-quality online version is free or costs a tenner at most.

The original painting is worth so much because of its provable authorship, as well as scarcity—there can only be one in the world. On top of that, it is the product of one of the greatest minds of all time.

That concept is not so different from the dynamics that exist with the written word. “You can buy a copy of a Harry Potter book for $9.99 via Amazon (or $0.00 for Prime Members) or pay $6,500 for a first edition copy. The words are the same, the story is the same; in short, the art has not changed. The difference is the degree of scarcity,” explains Gabriele.

Although the variable of scarcity has played a big part in the career of many traditional artists, it has no use to those who create and share their pieces online. As Kevin Kelley explained, the internet is fundamentally a “copy machine.” It is effectively free and easy to create multiple versions of the same product. Death to scarcity; the internet made abundance the norm. As tech and culture further co-mingle, we’re entering an age of abundance, but even then, our love of ownership might take over.

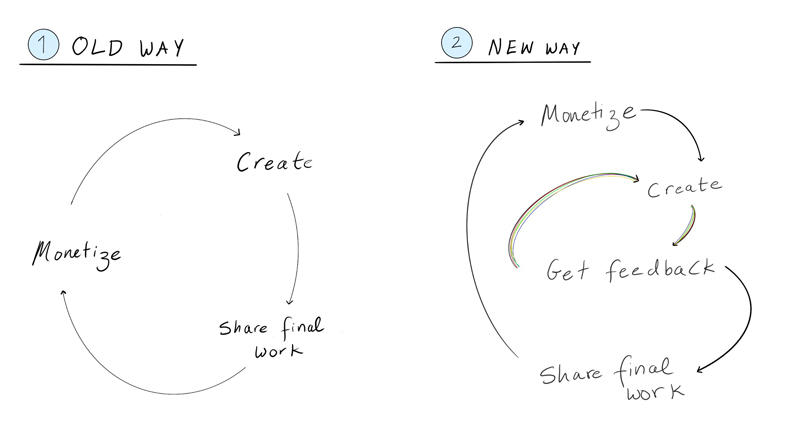

And that’s precisely what NFTs can solve: the problem of abundance. In The Generalist, Gabriele explains that by introducing scarcity, NFTs alter the relationship between audience and art in two fundamental ways. First, by shifting from access to ownership.

As of now, our relationship to art objects on the internet is one of access. Even if paywalled, we do not own anything; we merely have a ticket to look around for a bit. And that was fine for a while. But now, NFTs are opening up the path for actual ownership. Questions of provenance, authenticity, and scarcity are solved by using the blockchain, which is transparent and verifiable. By making the construction of scarcity simple and safe, unlike before, NFTs have unleashed a new generation of appreciators and investors in art.

Secondly, NFTs also blur the boundaries between artist and audience by allowing audience members to partake in the creation of the work. This might involve supporting a project upfront in exchange for ownership and voting power over the direction of an artistic endeavour.

So what’s stopping us from doing the exact same thing with writers as well as other industries—many of which have already started playing around with NFTs? Of course, it’s not that simple but I’ll let Gabriele light the way for other publications and journalists to follow.