Caffeinated bumblebees could be used to boost crop production, a new study finds

Does caffeine inject a sense of purpose to your mornings? If so, congratulations, you have something revolutionary in common with bumblebees. A new study, published in the biweekly peer-reviewed scientific journal Current Biology, has concluded that caffeinated bees are better equipped to find target crops—regardless of whether the crops contain caffeine.

To date, various studies have proven caffeine’s potential in improving bee memory and thereby boosting their efficiency as foragers and pollinators. The experiments found honeybees retaining memories of the odour and preferentially returning to flowers that contained caffeinated nectar. However, the team of researchers, led by Sarah Arnold, a senior lecturer of insect behaviour and ecology at the University of Greenwich, have now decoupled the “rewarding effects of caffeine” from the stimulant’s actual effect on bee memory—thereby devising an experiment that provided doses of caffeine only at the nest.

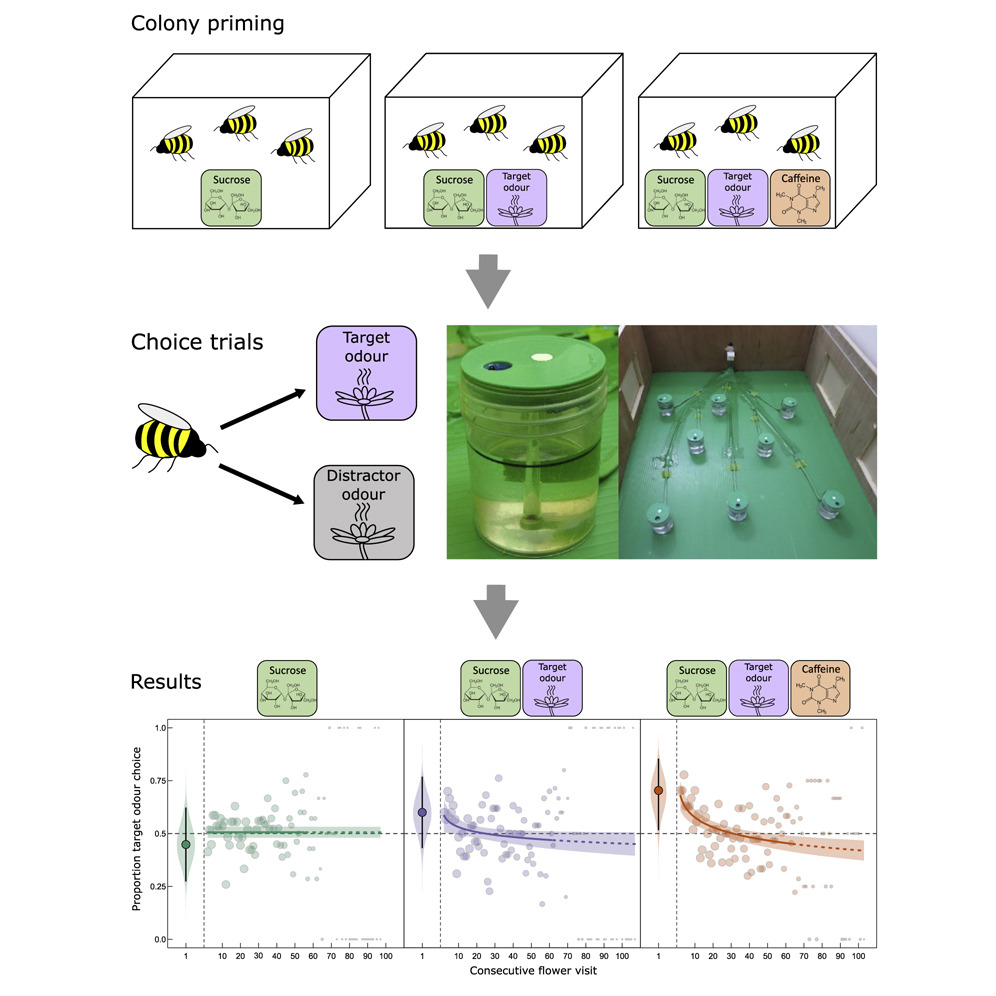

The study involved 86 inexperienced bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) divided into three groups based on the type of scent wafted through their nest. The first group was exposed to a sugary solution, the second to an artificial odour reminiscent of strawberry flowers coupled along with the same sugary solution, and the third to a caffeinated version of the sugary solution along with the strawberry odour blend.

All the bees were then released into a flight arena covered with a green polypropylene sheet. The arena featured artificial flowers with the strawberry scent along with “distractor” flowers with another fragrance. Although both the flowers provided a sugar reward, neither of them were laced with caffeine. The electronic flowers were also designed to detect bee visits and refill automatically after 12 seconds.

“We were interested in seeing whether the bees would go for all of the flowers equally since they were all equally rewarded, or whether they go for the flowers that smell like the ones that they’ve been kind of trained on in the nest,” Arnold said in an interview with The Guardian.

70 per cent of the caffeinated bees visited the strawberry-scented flowers first, compared to 60 per cent of the bees that were primed with the strawberry scent alone. On the other hand, only 44.8 per cent of the bees that were exposed to the sugary solution—without the association to the strawberry smell—visited the strawberry-scented flowers first. Caffeine-primed bees were therefore concluded to have faster “floral handling” and flower-visiting speeds.

“We anticipated that caffeine should help focus the bees on the crop,” Arnold told VICE, adding how the results cemented the hypothesis of bumblebees seeking out smells they were exposed to inside their nest when they ventured outside. Surprisingly, the effects of caffeine were short lived and the caffeine-primed bees eventually stopped showing an affinity toward the strawberry scent.

“What we think is most likely is that the two sorts of robotic flowers in the arena (the synthetic strawberry flower odor and the distractor odor) both offered an equal food reward and were easy to find in a small and simplified environment,” Arnold explained. “So rapidly, the bees realised that whether they sought out the ‘primed’ odor or not, they received a good energetic reward of sugar solution and could visit either type of flowers.”

With the climate crisis straining wild populators including bees, moths, wasps, butterflies, beetles and birds, some farmers are relying on “managed pollinators” like commercial bumblebees to pollinate their crops. However, these bee colonies aren’t as efficient—with some refusing to leave their nests and others easily distracted by other scents in the vicinity. Previous research with caffeinated bees also involved putting the substance directly on flowers to attract them. This was impractical on a larger scale.

The insights from this experiment, however, has wider implications for the impact of caffeine on overall crop production. Food locating behaviours in free-flying bumblebees could be a good start to enhance the efficiency of commercial bees and ensure crops are pollinated. “In a field situation…the bees would have to deal with different weather conditions, they would have further to fly and other challenges,” Arnold cautioned, noting that it would take a successful field-scale trial before this approach could be used in the real world.

If the results are replicated, then everyone stands to benefit, she added. “The growers get more value for money out of their commercial bumblebees, the wild bees potentially get a bit less competition for their natural food resources. And, as consumers, hopefully, we also get more fruit.” It seems a caffeinated bee is indeed a busier bee.