How long would it take to travel a light year?

Our universe has a speed limit, and this limit is set by the speed of light which travels at the mind boggling pace of 186,282 miles per second, or 299,792 kilometres per second. That’s 670,6 million miles per hour, or 1.1 billion kilometres per hour. Basically, if you had the ability to travel at the speed of light, you would be able to do a complete cycle around the Earth seven and a half times each second. Imagine, for example, the speed at which Liz Truss was—and then very quickly wasn’t—the UK’s Prime Minister. So, when human hour’s turn to years, we’re talking light years in particular, how long would a light year take in human time?

The theory of relativity

Thanks to Albert Einstein’s trusty theory of relativity, which is based on two key concepts—special relativity and general relativity—we can figure this out. In layman’s terms, Einstein’s theory translates as everything is relative, but the speed of light is constant.

To warp your thinking a bit, consider rulers and clocks—these tools mark time and space and are not the same for different observers. However, if the speed of light is constant, as Einstein stated, then time and space cannot be absolute or uniform, they must instead be subjective. Einstein read the relationship between space and time, and noticed that their consequences were intertwined. In fact, space and time can no longer be independent. Don’t worry, we’re almost there.

We as humans have many misconceptions of time and space because time, for one, feels like it’s relentlessly moving forward. Time to us, flows, and has a direction that advances in an orderly fashion. Time has become like a backdrop in which all events take place in space, sequence and durations are measured. So, if you’ve ever felt as though the Kardashians’ ability to continuously create personal brands truly subverts time and space—you’re not alone.

However, this concept is challenged by Einstein’s theory of relativity whereby space and time convert into each other in such a way as to keep the speed and light constant for all observers. In other words, they depend on the motion of the observer who measures them—this is why moving objects appear to shrink. This theory is the infrastructure of our current understanding of the universe. So, how does this all relate to calculating the speed of light then?

Keeping the perspective of a viewer in mind, and bringing in an object that travels (which is essentially what we are measuring here) let’s say, a human that is travelling at the speed of light. To an observer, the size of the human would be miniature, but to the human travelling, they would remain their own size.

Time also passes slower the faster one goes, and mass also depends on speed. The relationship between mass and speed (or energy) is calculated with the formula E=mc^2, where E is energy, m is mass, and c is the speed of light.

How long would it take to travel a light year?

Now back to figuring out how long it would take us to travel a light year. If we were to measure distances in miles or kilometres, we would be working with enormous numbers. So, instead we measure cosmic distances in light years according to how fast light can travel in a year. I know, but bare with me.

According to Futurism, there are just about 31,500,000 seconds in a year, and if you multiply this by 186,000 (the distance that light travels each second), you get 5.9 trillion miles (9.4 trillion kilometres) which is the distance that light travels in one year.

The time that it takes humans to travel one light year is considerably longer than a year. To put it into context, it takes between six months and a year for us to reach Mars, which in light year terms, is 12.5 light minutes away. It took NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft almost ten human years to reach Pluto from Earth—which is ‘just around the corner’, only 4.6 light hours away.

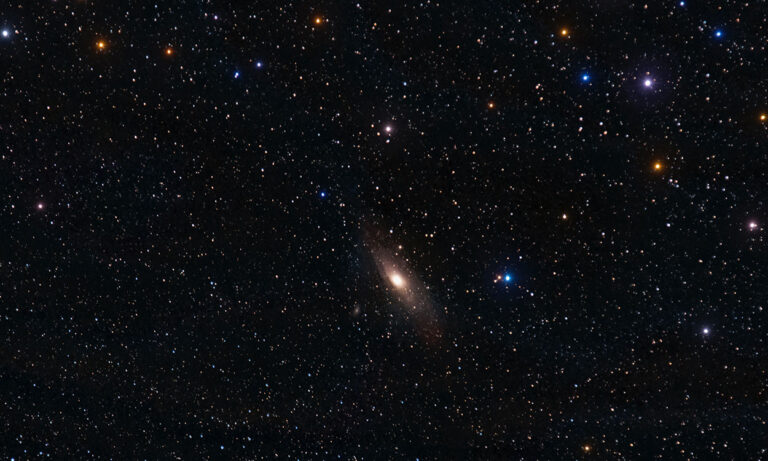

Let’s say we were a space shuttle that travelled five miles per second, given that the speed of light travels at 186,282 miles per second, it would take about 37,200 human years to travel one light year. That’s a long time, and what would you see? Well, not much, unfortunately. You’d be closer to the centre of our own galaxy, but with a further 26,000 light year distance still to travel.

Will light-speed space travel ever be possible?

Okay, we know how long it’s going to take—albeit might not be as impressive once we arrive—but is there a possible way to travel as far as a light year?

From our current understanding, unfortunately no. According to Britannica, Einstein’s aforementioned theory of relativity clearly states that the speed of light is a cosmic limit that cannot be surpassed. And so, light-speed travel would be a physical improbability—especially if it involved mass, such as a human or spacecraft.

It should be noted that Musk may have once considered pursuing the impossible feat, but I imagine he’s far too preoccupied taking over Twitter.

So, while you may be craving some of the magnificent sights captured by the recent James Webb Telescope, I’m afraid you netizens might have to rely on the confines of the internet.