Rats love bopping their heads to Lady Gaga, study discovers

Apart from raiding kitchens, hitching rides, and gnawing on literally everything in your attic, it turns out that rats are Little Monsters too.

A new study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances, has discovered that the rodents are able to perceive musical beats and bop their heads along to the rhythm—an attribute previously thought to exist only in humans.

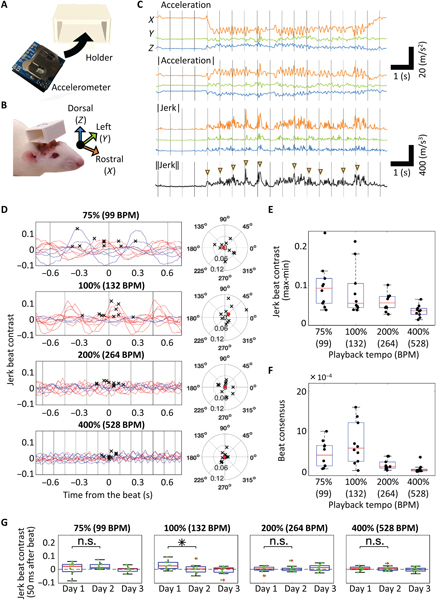

Researchers at the University of Tokyo first fitted rats with wireless, miniature accelerometers that could detect their slightest head movements. They were then played one-minute excerpts from Lady Gaga’s ‘Born This Way’, Queen’s ‘Another One Bites the Dust’, Mozart’s ‘Sonata for Two Pianos in D major, K. 448’, ‘Beat It’ by Michael Jackson, and ‘Sugar’ by Maroon 5. True Spotify playlist on shuffle energy, if you ask me.

These minute-long excerpts were streamed at four different speeds for ten rats and 20 human participants, who also wore accelerometers on headphones.

The results? While the researchers believed rats would prefer faster music, given the fact that their bodies—including heartbeat—work at a faster pace, their innate beat synchronisation abilities actually mirrored those of their human counterparts in the range of 120 to 140 beats per minute (bpm). So it’s no surprise that the Little Monsters bopped to ‘Born This Way’, which is set at a steady 124 bpm.

What’s more is that the team also found rats and humans jerked their heads to the beat in a similar rhythm, and that the level of head jerking decreased the more the music was sped up.

“Rats displayed innate—that is, without any training or prior exposure to music—beat synchronisation most distinctly within 120-140 bpm, to which humans also exhibit the clearest beat synchronisation,” Associate Professor Hirokazu Takahashi of the University of Tokyo said in a press release.

While bottomless scrolls on TikTok are bound to feature animals dancing and bopping along to music, the study in question is one of the first scientific investigations into the phenomenon. “To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on innate beat synchronisation in animals that was not achieved through training or musical exposure,” Takahashi mentioned in this regard, adding that the discovery feels like an insight into the creation of music itself.

“Next, I would like to reveal how other musical properties such as melody and harmony relate to the dynamics of the brain. I am also interested in how, why, and what mechanisms of the brain create human cultural fields such as fine art, music, science, technology, and religion,” Takahashi continued.

“I believe that this question is the key to understanding how the brain works and developing the next-generation AI.”