Rise of necrobots: scientists are turning dead spiders into zombie robots

From bringing dead fox terriers back to life with a seesaw to rendering fish carcasses transparent—only to dye their skeletal system into art pieces—scientists have been performing offbeat experiments on deceased animals for ages. Now, researchers from Rice University, Texas, have found a way to channel an arachnophobe’s worst nightmare by repurposing lifeless wolf spiders into robots… capable of lifting objects like a claw machine.

Let’s begin with an anatomy lesson before we dive further into the Frankenstein-esque experiment, shall we? Unlike biceps and triceps in humans, spiders don’t have antagonistic muscle pairs to move their limbs. Instead, they rely on blood pressure and flexor muscles that allow their legs to curl inward. A prosoma chamber, or cephalothorax, in their head then contracts—sending inner body fluid to their legs that allow spiders to extend them using hydraulic pressure.

It’s for this reason that arachnids curl up after they die. Their heart stops beating and they lose the ability to pressurise their bodies.

“We were moving stuff around in the lab and we noticed a curled up spider at the edge of the hallway,” said lead author Faye Yap in a press release. At the time, the scientists were super interested to find a way in which they could leverage the mechanism in question.

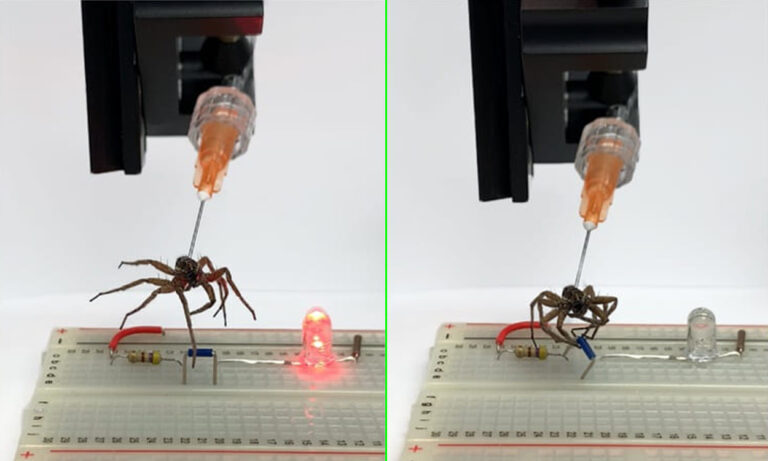

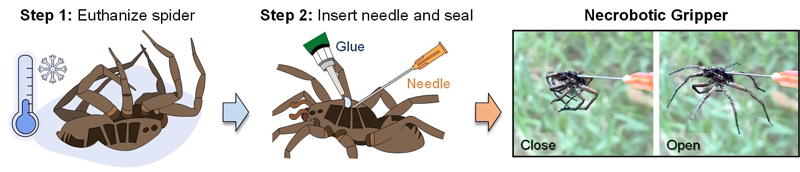

So, the team inserted a needle into the spider’s prosoma chamber and created a seal around its tip with a dab of superglue. The other end of the needle was connected to a handheld syringe which delivered a tiny puff of air—enough to activate the spider’s legs. They were then able to achieve a full range of motion in less than a second.

“We took the spider, we placed the needle in it not knowing what was going to happen,” Yap admitted in a video published by Rice University. “We had an estimate of where we wanted to place the needle. And when we did, it worked, the first time, right off the bat. I don’t even know how to describe it, that moment.” Daniel Preston of Rice University’s George R. Brown School of Engineering then went on to dub the novel area of research as “necrobotics.”

“It happens to be the case that the spider, after it’s deceased, is the perfect architecture for small scale, naturally derived grippers,” Preston said in the press release. “This area of soft robotics is a lot of fun because we get to use previously untapped types of actuation and materials. The spider falls into this line of inquiry. It’s something that hasn’t been used before but has a lot of potential.”

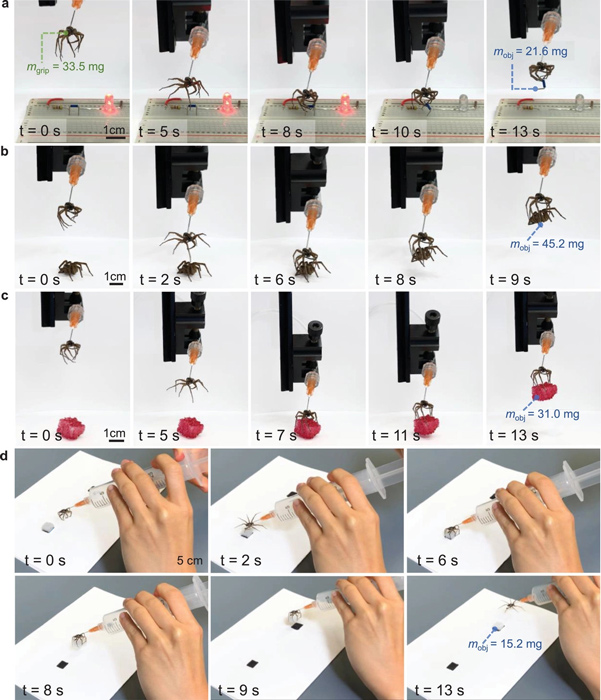

The researchers were able to make the lifeless spiders grip large, delicate and irregularly-shaped objects firmly and softly without breaking them. The testing also proved how the necrobots were capable of lifting more than 130 per cent of their own body weight.

They also made the mechanical grippers remove a jumper wire attached to an electronic breadboard, move a block of polyurethane foam and even lift another spider of about the same size as the test subject.

So how can the lab’s work be turned from a cool stunt to a useful piece of technology? “There are a lot of pick-and-place tasks we could look into, repetitive tasks like sorting or moving objects around at these small scales, and maybe even things like the assembly of microelectronics,” Preston said.

“Another application could be deploying it to capture smaller insects in nature because it’s inherently camouflaged,” Yap added. Preston further highlighted how spiders are biodegradable, so using them as robot parts would cut the amount of waste in robotics. “We’re not introducing a big waste stream, which can be a problem with more traditional components,” the expert mentioned in this regard.

While both Preston and Yap are aware that the experiments are nightmare fuel, they believe what they’re doing doesn’t qualify as ‘reanimation’. “Despite looking like it might have come back to life, we’re certain that it’s inanimate, and we’re using it in this case strictly as a material derived from a once-living spider,” Preston said. “It’s providing us with something really useful.”