The L to the OG obsession: Unpacking Succession’s weird and multi-layered relationship with rap

The world of Succession is filled with contradictions. We view insanely rich people often dressed down in baseball caps and bomber jackets; characters in refined, luxurious environments spouting out inventive sexual expletives or witnessing the mythological media giant Logan Roy who loomed impossibly large over all others suffering the ironically undignified end of randomly dying in an aeroplane toilet.

But there’s another feature that’s had a bizarre presence in the show: rap music. Speaking to Polygon, Succession composer Nicholas Britell said “hip hop is the most important form of modern music” and deliberately threaded hip hop beats into the main theme to provide it with rhythm, melody and that disconcerting bass. Rapper Pusha T even hopped onto a remix of the theme. Often used to form a punchline, Succession has had a consistent link with the genre from the beginning. The funny juxtaposition of whiteness, wealth and rap lyrics can be a window to social and racial dynamics—even in the almost complete absence of actual Black characters in the show. So what exactly does Succession’s weird relationship with rap tell us?

No character is more explicitly imbued in the genre than Kendall. The first time we meet him (a man who swings wildly from impossibly overconfident to deeply depressed and insecure), he’s pumping himself up in the backseat to the Beastie Boys ‘An Open Letter to NYC’ with an excruciating cut to just his falsetto voice singing the lyrics. We see him unconvincingly attempt to associate with rappers in series one, wearing a statement chain and inviting a “Tiny Wu-Tang Clan” set to perform for his 40th birthday in season three.

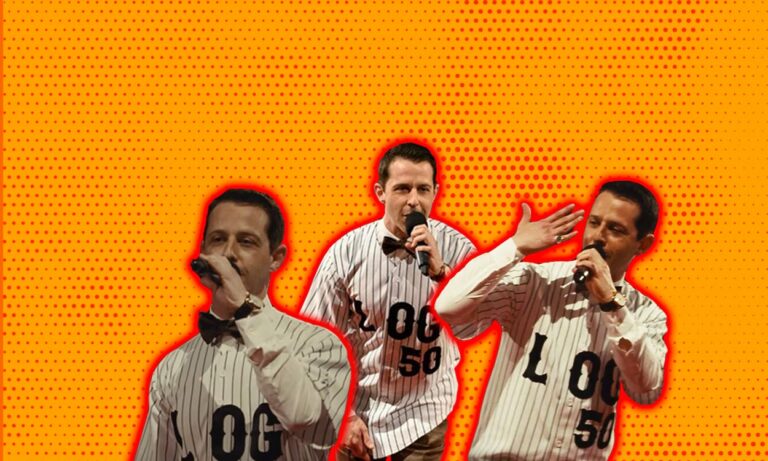

Most infamously, Kendall dons a pinstripe baseball shirt and performs ‘L to the OG’, a cringe-worthy tribute to his father so enduring that it’s left audiences terrified every time we’ve seen that man get on a stage since. Watching wealthy white people like Kendall awkwardly attempt to insert themselves into traditionally Black creative spaces is meant to be funny. We’re meant to find it unhinged that a 40-something-year-old rich white guy shouts out to an unwilling audience, “My boy Squiggle cooked up this beat for me.”

But underneath the comedic angle, there is a sinister commentary about American racial dynamics, and how antithetical figures like the Roys are to the values rap and hip hop is actually built on. Some of the earliest releases of the hip hop genre were infused with political messaging. Harlem World Crew’s 1980 release ‘Rappers Convention’ had lyrics designed like a radical news story, or GrandMaster Flash And The Furious Five’s ‘The Message’ eloquently encapsulates the material suffocation of being Black in America.

NWA’s rebellious classic ‘Fight The Power’ exudes lyrical rage and speaking truth to power. Much of rap and hip hop’s origins lie in Black radicalism, being anti-establishment, anti-police, and anti-white supremacy. After laughing at the impossibly satirical image of Kendall flashing his gold pinky ring, we have to grapple with what it really means to have someone so privileged cloak themselves in a radical persona to do things that are largely self-serving, like desperately seeking to own a corporation that specialises in “rollercoasters and hate speech.”

Kendall cosplays as a radical constantly, trying to prove he’s different from his father, as though he is some sort of counter-cultural insurgent in the family. He’s a self-styled anti-patriarchal (remember when he yelled “fuck the patriarchy!” as he strolled into another swanky billionaire event?) wannabe tech bro who claims to be different from legacy media dinosaur Logan—yet his daddy issues of constantly wanting to ape Logan suggest otherwise.

Rap’s radical roots go beyond just a love of the genre for Kendall, but are a useful tool for building an image of himself that is an illusion. In episode eight of the final series, his ex-wife Rava questions rightly why he wants to own the reactionary rightwing news organisation ATN which is likely increasing racial hostility faced by their own daughter. Kendall later decides on pretty shaky grounds to call the election for neo-Nazi presidential candidate Jared Mencken as a power play, seemingly forgetting what the long-term consequences to the fabric of the country could be, to have someone calling for more purity, in power.

The Black hypermasculinity imbued in some rap is clearly also of use to Kendall. Shows of physical strength, a lack of emotion, dominance over women, and extreme resilience have been common features of the genre. For Kendall, his love of rap reflects his empty machismo, masking his frequent sad boy lows (now well-documented in endless Twitter memes).

In my Succession era (I haven’t seen any of the show except the memes) pic.twitter.com/BS6vBkyAPK

— Robbie 🏴 (@robbo_mcf) May 16, 2023

“Ken W A” as he’s mockingly referred to, performs his paternal tribute after having twice tried to take over Logan’s company and been effectively bribed into total subservience. Rather than exuding power and self-expression, the performance becomes even more uncomfortable because the audience understands the tragedy of how much pain and delusion Kendall is in.

Paradoxically, the perceived physical strength and dominance of Black men is both feared and admired in white America. Jay-Z’s ‘Takeover’ plays in series four episode four, a display of dominance and hyper-aggression over one’s competitors. It may serve as a great emotional pump up in the moment for the likes of Kendall, but for Black men, the perception that they are hyper-masculine feeds into a social system that cultural writer Bell Hooks said had “no transformative power, no ability to intervene on the politics of domination, and turn the real lives of Black men around.”

The material consequences of Black men having to be viewed this way, from police brutality to incarceration and general violence, strikes as very different to a rich white man choosing to chuck on these tropes to get a quick ego boost before a board meeting.

Rap has arguably gone on an evolution from overtly political and anti-establishment, to embodying the very ideas it was created to oppose: hustle culture, capitalism and individualism. We’re all familiar with phrases like “get your money up,” “I’m a hustler baby” or the somewhat extreme “get rich or die trying.”

The obsession with grinding 24/7 and that success is about “working hard enough” is a fallacy that extremely wealthy people like Kendall benefit significantly from, to justify their position as billionaire overlords. It’s easier to feel self-righteous about your actions if you can masquerade as a hustler who’s made it through struggles to get here.

There is also a relationship between tech and rap/hip hop. Kendall likes to see himself as cutting edge, constantly spouting out corporate tech bro jargon like “I think Vaulter is the shizz.” Several rappers have transitioned into tech entrepreneurs in the last decade—and technological advances have been part of how rap, hip hop, MC-ing and DJ-ing have expanded. Perhaps Kendall’s association with more modern rap offshoots is actually fitting, rather than purely jarring.

Among all these musical references to race, there is a notable absence of actual Black people in the show. Succession’s Black characters tend to be extremely peripheral in this otherwise white world, occupying mostly servile positions and often being easily disposed of. Jess as Kendall’s long-suffering assistant is undervalued, and lawyer Lisa is quickly discarded in series three when she doesn’t immediately meet Kendall’s ridiculous demands; and clearly is picked for the optics of being a Black woman leading a crusade against legacy allegations of sexual abuse against Waystar Royco.

Kendall attempts to exploit late-night comedian Iwobi, by going on her show and having her drag him for having a “caucasian rich brain” in an attempt to seem more relatable. Blackness, like everything else in the Roy world, is a utility to win more power, but Black people themselves do not thrive in a Roy-driven world.

In short, the show doesn’t need to performatively showcase more substantial Black characters, because Succession has never been about people who are capable of changing for the better, but the corrupting nature of money, power, patriarchy and whiteness. Succession’s relationship with rap perfectly showcases this, and it’s commendable that the writers have chosen to accurately depict the contradictions of whiteness at the highest echelons of the corporate, media and political world. And that’s worth all the cringe rap lyrics in the world.